Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited retinal dystrophies characterized by progressive degeneration of the retina’s photoreceptor cells, particularly the rods and cones. These photoreceptor cells are responsible for converting light into electrical signals that the brain interprets as vision. RP primarily affects the rods, which are responsible for low-light vision and peripheral vision, resulting in a gradual loss of night vision and peripheral visual field. As the condition progresses, the cone cells responsible for color vision and central vision may be affected, potentially leading to significant visual impairment or blindness.

The Genetic Basis of Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis Pigmentosa is a genetic disorder with a complex inheritance pattern. Depending on the genetic mutation, the condition can be inherited as autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked. Over 60 different genes have been identified as causing RP, with each playing an important role in the development, function, or maintenance of photoreceptor cells or the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).

- Autosomal Dominant RP: This inheritance pattern requires only one copy of the mutated gene from one parent to cause the disease. Autosomal dominant RP has a milder and slower progression than other forms. It accounts for between 20 and 25% of all RP cases. Individuals with this type of RP typically develop symptoms in their second or third decade of life.

- Autosomal Recessive RP: For the disease to manifest, the mutated gene must be present in two copies, one from each parent. Autosomal recessive RP is more common, accounting for between 50 and 60 percent of cases. This form frequently has an earlier onset and faster progression than the autosomal dominant form. Symptoms may appear in childhood or adolescence.

- X-Linked RP: Mutations in genes on the X chromosome cause this condition. Because males have only one X chromosome, they are more severely affected by this type of RP. Females with two X chromosomes may carry the mutated gene and experience milder symptoms. X-linked RP accounts for 10-15% of all RP cases and is frequently associated with more severe and rapid progression of vision loss, with symptoms usually appearing in childhood or early adolescence.

- Mitochondrial and Digenic Inheritance: In rare cases, RP can be inherited via mitochondrial DNA (passed down from mother to child) or via digenic inheritance, which requires mutations in two different genes to cause the disease.

Pathophysiology of Retinitis Pigmentosa

The progressive degeneration of photoreceptor cells in retinitis pigmentosa is characterized by a specific sequence. Initially, rod photoreceptors, which are responsible for night and peripheral vision, are impacted. The loss of rod function causes symptoms such as night blindness (nyctalopia) and a narrowing of the peripheral visual field, also known as “tunnel vision.”

Cone photoreceptors, which are located in the central retina and are responsible for color vision and high-acuity vision, begin to degenerate as the disease progresses. This causes additional visual impairment, including difficulty distinguishing colors and loss of central vision, which is essential for tasks like reading, driving, and recognizing faces.

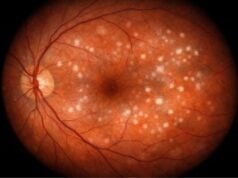

Histologically, an individual with RP’s retina exhibits photoreceptor cell loss as well as characteristic pigmentary changes. These changes, known as bone spicule pigmentation, occur when pigment-laden cells migrate from the retinal pigment epithelium to the retina’s inner layers. In addition, thinning of the retina, particularly in the mid-peripheral regions, and eventual atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid are common findings in the disease’s advanced stage.

The progressive degeneration of photoreceptors and associated retinal cells causes a cascade of secondary changes in the retina, such as retinal circuitry remodeling and synaptic loss between photoreceptors and downstream neurons (bipolar and ganglion cells). This remodeling exacerbates retinal function and contributes to the overall decline in visual acuity.

Clinical Features and Symptoms

The clinical manifestation of retinitis pigmentosa varies greatly depending on the specific genetic mutation, mode of inheritance, and stage of the disease. However, the condition is characterized by a number of common symptoms and clinical signs:

- Night Blindness (Nyctalopia): One of the first and most common symptoms of RP is the inability to see in low-light situations. This symptom is directly related to the early loss of rod photoreceptors, which are responsible for vision in low light. Patients may struggle to navigate dark environments, such as driving at night or moving around in a dimly lit room.

- Peripheral Vision Loss: As the disease progresses, patients experience a gradual loss of peripheral vision, also known as “tunnel vision.” This occurs when the rod photoreceptors in the mid-peripheral retina degenerate, causing constriction of the visual field. The peripheral vision loss may be subtle at first, but it can become more pronounced over time, impairing one’s ability to perform daily tasks such as walking, driving, or participating in sports.

- Visual Field Defects: Scotomas, or areas of vision loss, in the peripheral field are common in patients with RP. As the condition progresses, these scotomas may merge, resulting in a significant reduction in functional visual field.

- Photopsia: Patients with RP frequently describe seeing flashes of light or flickering in their peripheral vision, which is known as photopsia. These visual phenomena are thought to be caused by the ongoing degeneration of photoreceptor cells, which disrupts normal retinal activity.

- Color Vision Deficiency: As cone photoreceptors deteriorate, patients may have difficulty distinguishing between colors, especially in low-light conditions. This symptom typically appears later in the disease’s progression and is associated with cone cell degeneration in the central retina.

- Central Vision Loss: In advanced stages of RP, cone photoreceptor degeneration in the macula can impair central vision. This can make it difficult to read, recognize faces, and complete tasks that require detailed vision. Central vision loss has a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life and independence.

- Progressive Vision Loss: The progression of vision loss in RP is typically slow and insidious, spanning several decades. However, the rate of progression varies greatly between individuals and may be influenced by factors such as genetic mutation, environmental exposure, and overall health.

Complications of Retinitis Pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa is associated with several potential complications, which can further impact vision and overall eye health.

- Cataracts: People with RP are more likely to develop cataracts, particularly posterior subcapsular cataracts, at a younger age than the general population. Cataracts can exacerbate vision loss by reducing the amount of light that reaches the retina.

- Macular Edema: Some patients with RP develop cystoid macular edema (CME), which is fluid buildup in the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for detailed vision. CME can cause further decline in central vision and may necessitate specialized treatment to manage.

- Glaucoma: Glaucoma is more common in RP patients, which can add to the overall burden of vision loss. Glaucoma is characterized by elevated intraocular pressure, which damages the optic nerve.

- Retinal Detachment: Although uncommon, retinal detachment can occur in patients with advanced RP due to retinal thinning and the formation of peripheral retinal tears. Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that requires immediate surgical intervention to avoid permanent vision loss.

- Depression and Anxiety: The progressive nature of vision loss in RP can cause significant emotional and psychological difficulties. Patients may feel isolated, depressed, or anxious as they deal with the loss of independence and the impact of vision loss on their daily lives.

Epidemiology and Demographics

Retinitis pigmentosa is one of the most common inherited retinal dystrophies, with an estimated prevalence of one in every 4,000 people globally. The condition affects people of all ethnicities and geographical regions. While RP can develop at any age, symptoms usually appear in childhood or adolescence and progress over time. The rate and severity of vision loss can vary greatly depending on the genetic mutation and inheritance pattern.

Retinitis pigmentosa affects both men and women, but certain forms of the disease, such as X-linked RP, are more prevalent and severe in men. Because of the genetic nature of the condition, people with a family history of RP are more likely to develop the disease and may benefit from genetic counseling and early screening.

Understanding the genetic basis, pathophysiology, and clinical presentation of retinitis pigmentosa is critical for accurate diagnosis and successful treatment of this complex and difficult condition.

Methods for Diagnosing Retinitis Pigmentosa Effectively

To diagnose retinitis pigmentosa, a clinical examination, patient history, genetic testing, and advanced imaging techniques are all required. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical for guiding treatment, managing symptoms, and offering genetic counseling to affected people and their families.

Clinical Examination

The clinical examination for retinitis pigmentosa (RP) starts with a thorough assessment of the patient’s visual function. The ophthalmologist will usually begin by assessing visual acuity, which measures the sharpness of central vision. Although visual acuity may be relatively stable in the early stages of RP, it frequently deteriorates as the disease progresses, particularly when the central retina or macula is involved.

Color Vision Testing is an important part of the clinical examination. Patients with RP, especially in the later stages, may have color vision problems, particularly distinguishing between blues and greens. These deficiencies are due to the degeneration of cone photoreceptors, which are responsible for color perception.

Visual Field Testing is critical for determining the extent and pattern of peripheral vision loss, which is characteristic of RP. Visual field tests, such as automated perimetry, can help map out scotomas (areas of vision loss) and provide important information about the disease’s progression. In RP, the visual field frequently exhibits a distinct pattern of mid-peripheral scotomas that gradually encroach on the central visual field, resulting in tunnel vision.

The fundus examination, which uses an ophthalmoscope or slit-lamp biomicroscopy, allows the ophthalmologist to see the retina directly. Several distinguishing features of RP include:

- Bone Spicule Pigmentation: One of the most distinguishing features of RP is the presence of bone spicule pigment in the mid-peripheral retina. These are pigment clumps that migrate from the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) to the inner retinal layers, forming a pattern similar to bone spicules.

- Attenuation of Retinal Blood Vessels: In patients with RP, the retinal arterioles frequently narrow and attenuate, indicating the loss of retinal tissue and photoreceptor cells.

- Optic Disc Pallor: Over time, the optic disc, which is where the optic nerve exits the retina, may become pale or waxy due to nerve fiber degeneration and ganglion cell loss.

- Retinal Thinning: In advanced cases, the retina may appear thinner and more translucent, especially in areas where photoreceptor loss is severe.

Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT)

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that produces high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina. OCT is a valuable tool in the diagnosis and management of retinitis pigmentosa because it allows for detailed visualization of the retinal layers as well as the detection of structural abnormalities.

In patients with RP, OCT can reveal several key features.

- Thinning of the Outer Retinal Layers: One of the most consistent findings in RP is the thinning of the outer retinal layers, specifically the photoreceptor layer and the outer nuclear layer, which houses the photoreceptor cell bodies. This thinning is most noticeable in the mid-peripheral retina, but it can spread to the macula as the disease progresses.

- Cystoid Macular Edema (CME): OCT is especially useful in detecting cystoid macular edema, which is a common complication of RP. CME manifests as cystic spaces within the macula filled with fluid, which can severely impair central vision.

- Loss of the Ellipsoid Zone: The ellipsoid zone, which corresponds to the photoreceptor inner segment/outer segment junction, may become disrupted or absent in RP, indicating significant photoreceptor damage.

OCT is also useful for tracking disease progression and response to treatments like corticosteroids or anti-VEGF therapy for CME.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Electroretinography (ERG) is a diagnostic test that detects the retina’s electrical activity in response to light stimuli. ERG is especially useful in the diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa because it provides a functional assessment of the retinal photoreceptors and can detect abnormalities before significant symptoms appear.

ERG in patients with RP typically shows a significant reduction in the amplitude of both rod and cone responses, indicating widespread photoreceptor dysfunction. The rod response is typically affected first, resulting in a reduced scotopic (low-light) response, whereas the cone response may remain relatively intact in the early stages but gradually declines as the disease progresses.

ERG is also useful for distinguishing RP from other retinal dystrophies and determining the severity of disease. The test can be done as a full-field ERG, which measures the overall retinal response, or as a multifocal ERG, which provides more detailed information about retinal function in specific areas.

Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF)

Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) is a non-invasive imaging technique that detects the natural fluorescence of lipofuscin, a pigment that accumulates in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) as a result of photoreceptor degradation. FAF is especially useful for detecting areas of retinal atrophy and determining the overall health of the RPE.

In retinitis pigmentosa, FAF can reveal a distinctive pattern of hyperautofluorescence around the macula, known as the “ring sign,” which corresponds to areas of ongoing photoreceptor degeneration. As the disease progresses, areas of hypoautofluorescence (low fluorescence) may appear, indicating RPE atrophy and additional photoreceptor loss.

FAF is also useful for tracking the progression of RP and detecting early retinal changes before significant vision loss occurs.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is critical in the diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa, especially when the inheritance pattern is unclear or there are multiple family members affected. Identifying specific gene mutations can help confirm a diagnosis, provide prognostic information, and direct genetic counseling for affected people and their families.

Targeted gene panels, whole-exome sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing are some of the techniques used for genetic testing. These tests can detect mutations in known RP-associated genes and help determine the specific inheritance pattern, which is useful for family planning and assessing the risk of passing the condition down to future generations.

Furthermore, genetic testing is becoming more important as gene-based therapies for RP are developed and tested in clinical trials. Identifying the specific genetic mutation can aid in determining eligibility for these emerging therapies.

Fluorescein Angiography(FA)

Fluorescein angiography (FA) is a diagnostic test that involves injecting a fluorescent dye into the bloodstream and taking a series of photographs while the dye circulates through the retinal blood vessels. FA is especially useful in determining retinal blood flow, identifying areas of capillary non-perfusion, and detecting retinal neovascularization.

In retinitis pigmentosa, FA may be used to evaluate complications such as cystoid macular edema or to determine the extent of retinal ischemia in cases where neovascularization is suspected. FA can provide detailed information about the retinal vasculature, assisting with treatment decisions such as laser photocoagulation or anti-VEGF therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa includes a number of other retinal dystrophies and degenerative conditions that can cause similar symptoms. These conditions include the following:

- Usher Syndrome is a condition characterized by both RP and hearing loss. Genetic testing can aid in distinguishing Usher syndrome from non-syndromic RP.

- Cone-Rod Dystrophy: A retinal dystrophy that primarily affects the cone photoreceptors, resulting in early loss of color and central vision, with rod involvement later on. ERG and genetic testing are critical in distinguishing cone-rod dystrophy from RP.

- Choroideremia is a rare X-linked retinal dystrophy that affects both the choroid and the retina, causing progressive vision loss. Clinical examination, FAF, and genetic testing can help distinguish choroideremia from RP.

Retinitis Pigmentosa Management

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is difficult to manage because it is progressive and currently incurable. However, a combination of therapies, supportive care, and lifestyle changes can aid in symptom management, slowing disease progression, and maintaining quality of life. Ophthalmologists, genetic counselors, low vision specialists, and, in some cases, mental health professionals are typically involved in RP management.

Pharmaceutical Interventions

While RP has no cure, certain pharmacological treatments can help manage complications and potentially slow the disease’s progression:

- Vitamin A Palmitate: Research indicates that high-dose vitamin A palmitate may slow the progression of RP in some patients, particularly those with specific genetic mutations. The recommended daily dose is 15,000 IU, but this should only be taken with the supervision of an ophthalmologist due to potential side effects such as liver toxicity and bone thinning. Patients undergoing this therapy must have their liver function and vitamin A levels monitored on a regular basis.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: According to some studies, a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids, specifically docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), may benefit patients with RP. Omega-3 fatty acids are thought to promote retinal health and may enhance the effects of vitamin A therapy. However, more research is required to confirm their effectiveness in slowing disease progression.

- Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: Patients with cystoid macular edema (CME), a common complication of RP, can benefit from carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as acetazolamide or topical dorzolamide, which reduce fluid accumulation in the macula and improve central vision. These medications help to reduce fluid retention in the retina, thereby lowering macular edema.

- Anti-VEGF Therapy: When RP is complicated by neovascularization, anti-VEGF therapy may be used to prevent the formation of abnormal blood vessels and reduce the risk of vitreous hemorrhage. Intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents, such as ranibizumab or bevacizumab, can be effective in managing these complications, but they are not typically required in most cases of RP.

Genetic Therapy

Gene therapy is a new treatment option for RP, particularly for people who have certain genetic mutations. Luxturna (voretigene neparvovec) is the first FDA-approved gene therapy for inherited retinal disease. It is intended to treat patients with confirmed biallelic RPE65 mutation-associated retinal dystrophy. This therapy involves injecting a functional copy of the RPE65 gene directly into the retinal cells via subretinal injection, allowing the cells to produce the protein required for photoreceptor function.

Gene therapy is a significant advancement in the treatment of RP, with the potential to save or even restore vision in some patients. It is, however, currently limited to specific genetic mutations, with ongoing research focusing on developing gene therapies for other types of RP.

Retinal Implants and Prosthetics

Retinal implants and prosthetic devices are being developed to restore some level of vision in patients with advanced RP who have lost most or all of their vision. The Argus II retinal prosthesis, for example, is an FDA-approved device that captures images with a small camera mounted on glasses before processing and wirelessly transmitting them to a retina implant. The implant stimulates the remaining retinal cells, allowing the patient to perceive patterns of light and dark, which can aid in basic tasks like navigating a room or recognizing large objects.

While retinal implants do not restore normal vision, they can significantly improve the quality of life for patients with severe vision loss by restoring some visual perception. These devices are especially useful for people who have lost all or nearly all of their vision due to RP.

Low Vision Aids and Rehabilitation

For many RP patients, low vision aids and rehabilitation services are critical to maintaining independence and improving quality of life. Low vision aids, such as magnifying glasses, electronic magnifiers, screen readers, and closed-circuit television systems, can assist patients with daily tasks like reading, writing, and using a computer.

Vision rehabilitation programs may include training in the use of these devices as well as strategies for coping with vision loss, such as lighting optimization, contrast enhancement, and orientation and mobility techniques. Occupational therapy and counseling services can also help patients cope with the challenges of living with RP.

Lifestyle Changes and Supportive Care

Lifestyle changes are critical for managing RP and avoiding complications:

- Sun Protection: Patients with RP are frequently advised to wear UV-blocking sunglasses to protect their eyes from harmful ultraviolet rays, which can exacerbate retinal damage.

- Regular Eye Exams: Regular visits to an ophthalmologist or retinal specialist are required to monitor disease progression, manage complications, and adjust treatment as needed.

- Healthy Diet: A diet high in antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and leafy green vegetables may help maintain retinal health and supplement other treatments.

- Exercise: Regular physical activity can help maintain overall health and well-being, which is critical when managing a chronic condition such as RP.

Mental Health Support

Living with RP can be emotionally difficult, and many patients may develop depression, anxiety, or feelings of isolation as their vision deteriorates. Mental health support, such as counseling or therapy, can help people cope with the psychological effects of vision loss. Support groups and online communities can also be a valuable source of encouragement and support for those facing similar challenges.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Retinitis Pigmentosa: A Journey through Darkness and Light” by Robert L. Bray – This book offers a personal perspective on living with RP, providing insights into the challenges and triumphs faced by those with the condition.

- “Inherited Retinal Disease: A Practical Guide” by Stephen H. Tsang and Theodore L. Brafman – This comprehensive guide provides valuable information on the genetics, diagnosis, and management of inherited retinal diseases, including retinitis pigmentosa.

Organizations

- Foundation Fighting Blindness – This organization is dedicated to finding treatments and cures for retinal degenerative diseases, including retinitis pigmentosa. They provide resources for patients and families, support research, and offer information about clinical trials and emerging therapies.

- Retina International – A global umbrella organization representing patient-led charities and foundations, Retina International provides resources, advocacy, and support for individuals affected by retinal degenerative diseases, including retinitis pigmentosa.