The diaphragm is a vital muscular structure that plays a central role in respiration and overall body function. Acting as the primary muscle of breathing, it separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities while coordinating with the nervous and circulatory systems to support gas exchange, venous return, and core stability. Understanding its anatomy, function, and common disorders is crucial for maintaining respiratory health. This comprehensive guide explores the diaphragm’s intricate structure, dynamic physiological roles, and the conditions that may affect its performance. You will also find current diagnostic methods, treatment strategies, nutritional advice, and lifestyle tips to help you optimize diaphragm function and overall well-being.

Table of Contents

- Structural Blueprint & Composition

- Physiological Roles & Respiratory Dynamics

- Common Diaphragm Conditions & Symptoms

- Diagnostic Approaches & Tools

- Therapeutic Strategies & Interventions

- Nutritional Support & Supplementation

- Lifestyle Practices for Optimizing Function

- Reliable Resources & Further Reading

- Frequently Asked Questions

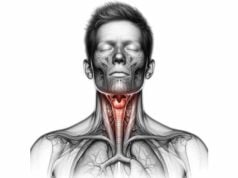

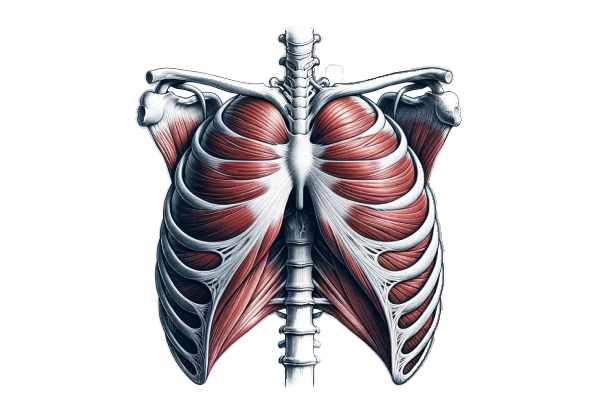

Structural Blueprint & Composition

The diaphragm is a broad, dome-shaped muscle that forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and the roof of the abdominal cavity. Its unique architecture—a complex interplay of muscle fibers and a central tendon—enables it to contract and relax rhythmically to facilitate breathing. In this section, we explore the detailed anatomy and composition of the diaphragm, highlighting its key components and their roles.

Muscular Architecture and Central Tendon

- Muscular Components:

The diaphragm comprises peripheral muscle fibers arranged radially around a central tendon. These fibers are divided into three parts: - Sternal Portion: Originating from the xiphoid process of the sternum, this segment contributes to the anterior portion.

- Costal Portion: Arising from the inner surfaces of the lower six ribs and their costal cartilages, this segment forms the bulk of the muscular structure.

- Lumbar Portion: Originating from the upper lumbar vertebrae via the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments, this section also forms the crura—robust muscle bundles that anchor the diaphragm to the spine.

- Central Tendon:

The central tendon is a broad, aponeurotic sheet situated at the core of the diaphragm. Unlike the contractile muscle fibers, the tendon is non-contractile but provides the essential scaffold to which the muscle fibers attach. Its elasticity and tensile strength are crucial for transmitting the forces generated during contraction and ensuring coordinated movement.

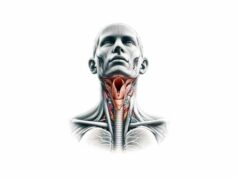

Openings, Hiatuses, and Anatomical Relationships

The diaphragm contains several key openings that allow the passage of vital structures between the thoracic and abdominal cavities:

- Aortic Hiatus:

Located posteriorly, this opening allows the aorta, thoracic duct, and occasionally the azygos vein to pass between cavities. - Esophageal Hiatus:

A muscular gap that permits the esophagus and the vagus nerve trunks to traverse the diaphragm. - Caval Opening:

Situated within the central tendon, this opening is essential for the passage of the inferior vena cava and the right phrenic nerve.

Innervation and Blood Supply

- Innervation:

The diaphragm receives its motor innervation primarily from the phrenic nerve, which originates from the cervical spinal roots (C3, C4, and C5). This nerve is indispensable for initiating and regulating the rhythmic contractions required for breathing. In addition, accessory nerves contribute to the sensory innervation of the diaphragm. - Vascular Supply:

The diaphragm is richly supplied with blood by multiple arterial sources: - Superior Phrenic Arteries:

Branches from the thoracic aorta, supplying the upper portion. - Inferior Phrenic Arteries:

Arise from the abdominal aorta or celiac trunk to supply the lower surface. - Musculophrenic and Pericardiophrenic Arteries:

These branches of the internal thoracic artery provide additional perfusion. Venous drainage mirrors the arterial supply, with corresponding veins (superior and inferior phrenic veins) returning blood to the systemic circulation.

Attachments and Functional Integration

The diaphragm is firmly anchored to the surrounding structures, which ensures its effective participation in respiration and postural stabilization:

- Sternal, Costal, and Lumbar Attachments:

The convergence of fibers from the sternum, ribs, and lumbar vertebrae provides a robust attachment network that supports the diaphragm’s contraction and relaxation during the respiratory cycle. - Integration with the Abdominal and Thoracic Cavities:

By forming a physical barrier between the thoracic and abdominal cavities, the diaphragm not only facilitates breathing but also contributes to the regulation of intra-abdominal pressure during activities such as coughing, sneezing, and defecation.

In summary, the diaphragm’s structural design—a combination of muscular fibers, a central tendon, strategic openings, and robust attachments—underpins its crucial role in respiration and overall bodily function. This sophisticated architecture ensures that the diaphragm can efficiently drive the mechanical process of breathing while providing stability and support for other vital functions.

Physiological Roles & Respiratory Dynamics

The diaphragm is the primary muscle responsible for breathing, and its rhythmic contractions are essential for ventilation. Beyond its role in respiration, the diaphragm contributes to several physiological processes that support both respiratory and systemic functions. This section explores the dynamic roles the diaphragm plays in maintaining health and facilitating bodily functions.

Primary Role in Respiration

- Inhalation Mechanism:

During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and flattens, increasing the volume of the thoracic cavity. This expansion creates a negative pressure gradient that draws air into the lungs, ensuring efficient oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide removal. The contraction of the diaphragm is the driving force behind the initial phase of breathing, setting the stage for effective gas exchange. - Exhalation Process:

In exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its dome-shaped resting position. This relaxation decreases thoracic cavity volume, increases intra-thoracic pressure, and expels air from the lungs. Although exhalation is typically passive, forced expiration during activities such as exercise involves accessory muscles, with the diaphragm’s relaxation remaining central.

Secondary Functions and Support Roles

- Regulation of Abdominal Pressure:

The diaphragm plays a pivotal role in generating intra-abdominal pressure. During activities like coughing, sneezing, defecation, and even lifting heavy objects, its coordinated contraction enhances abdominal pressure, providing necessary support and protection to the internal organs. - Facilitation of Venous Return:

The downward movement of the diaphragm during inhalation not only expands the thoracic cavity but also assists in drawing blood back to the heart. By decreasing pressure in the thoracic cavity, the diaphragm enhances venous return, particularly via the inferior vena cava. This mechanism is crucial for maintaining optimal circulatory dynamics and preventing venous congestion. - Postural Stability and Core Support:

In addition to its respiratory function, the diaphragm contributes to core stability. Its coordinated activity with the abdominal muscles and pelvic floor helps stabilize the spine and maintain proper posture. This support is particularly important during dynamic movements and physical exertion, ensuring that the body remains balanced and aligned.

Role in Lymphatic Flow and Immune Function

- Lymphatic Pump:

The rhythmic movement of the diaphragm during breathing acts as a natural pump for the lymphatic system. This movement facilitates the flow of lymphatic fluid, which is essential for immune surveillance, nutrient transport, and waste removal. - Immune Response Modulation:

Efficient lymphatic drainage, aided by diaphragmatic motion, supports the immune system by ensuring that pathogens and cellular debris are effectively cleared from the tissues.

Contribution to Vocalization and Speech

- Airflow Regulation:

The diaphragm’s control over the volume and pressure of air expelled from the lungs is critical for phonation. Its finely tuned contractions allow for variations in pitch and volume during speech and singing, making it an essential component of the vocal apparatus. - Support for Articulation:

By modulating the flow of air through the vocal cords, the diaphragm indirectly influences the clarity and quality of speech. This function is integral to effective communication and expression.

Dynamic Interplay with Accessory Respiratory Muscles

- Synergistic Action:

While the diaphragm is the primary muscle of respiration, its activity is complemented by accessory respiratory muscles, including the intercostals, scalenes, and sternocleidomastoid muscles. Together, they facilitate complex breathing patterns required during exercise, stress, or respiratory compromise. - Adaptive Response:

In situations of increased respiratory demand, such as physical exertion or respiratory illness, the diaphragm works in concert with these muscles to maximize lung ventilation and maintain adequate oxygenation.

In essence, the diaphragm’s physiological roles extend well beyond simple breathing. It is intricately involved in maintaining respiratory efficiency, supporting circulatory dynamics, stabilizing the core, enhancing immune function, and even enabling vocalization. Its versatility and dynamic adaptability underscore its central importance to overall health and functional performance.

Common Diaphragm Conditions & Symptoms

The diaphragm, despite its critical role in respiration, can be affected by a range of disorders and injuries. These conditions may arise from congenital defects, trauma, neuromuscular disorders, or inflammatory processes. Recognizing the clinical manifestations of diaphragm-related issues is essential for timely intervention and effective treatment.

Diaphragmatic Hernia

- Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia (CDH):

A developmental defect where an opening in the diaphragm allows abdominal organs to migrate into the thoracic cavity. CDH often presents in newborns with respiratory distress and compromised lung development. Immediate surgical repair is required to reposition the organs and restore proper lung function. - Hiatal Hernia:

In this condition, a portion of the stomach protrudes through the esophageal hiatus into the chest. Symptoms typically include heartburn, acid reflux, and chest discomfort. Management ranges from lifestyle modifications and medications to surgical intervention in severe cases.

Diaphragmatic Paralysis and Paresis

- Unilateral Paralysis:

Often resulting from phrenic nerve injury, unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis leads to reduced movement on one side of the diaphragm. Patients may experience dyspnea, especially when lying down, and decreased exercise tolerance. Fluoroscopy (sniff test) and ultrasound are key diagnostic tools. - Bilateral Paralysis:

More severe, bilateral paralysis affects both halves of the diaphragm, causing significant respiratory compromise. This condition may be associated with neuromuscular disorders and often requires ventilatory support as part of management.

Diaphragmatic Spasm and Hiccups

- Hiccups:

Caused by involuntary, spasmodic contractions of the diaphragm, hiccups are usually transient and benign. However, persistent hiccups lasting more than 48 hours can be a sign of underlying pathology and warrant further investigation. - Spasticity:

Diaphragmatic spasm may also occur due to irritation or injury, leading to recurrent painful contractions that interfere with normal breathing.

Diaphragmatic Injuries

- Traumatic Rupture:

Blunt or penetrating trauma can result in diaphragmatic rupture, where a tear in the muscle allows abdominal organs to herniate into the thoracic cavity. This is a surgical emergency as it may compromise both respiratory and gastrointestinal function. - Strain and Overuse:

Repeated heavy lifting, excessive coughing, or intense physical activity may strain the diaphragm, leading to pain and temporary dysfunction. Conservative treatment such as rest, analgesics, and respiratory therapy is usually sufficient.

Diaphragmatic Eventration

- Abnormal Elevation:

Eventration refers to an abnormal elevation of the diaphragm due to thinning or weakening of its muscle fibers. This condition may be congenital or acquired and can reduce lung capacity and cause respiratory discomfort. In symptomatic cases, surgical plication of the diaphragm may be indicated.

Neurological Disorders Affecting the Diaphragm

- Myasthenia Gravis:

This autoimmune disorder can weaken the diaphragm by impairing neuromuscular transmission, leading to respiratory insufficiency. Management includes anticholinesterase medications, immunosuppressants, and sometimes thymectomy. - Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS):

Progressive degeneration of motor neurons in ALS eventually leads to diaphragmatic weakness and respiratory failure. Supportive care with non-invasive ventilation is essential for maintaining respiratory function.

Other Conditions

- Diaphragmatic Fatigue:

Occurring during prolonged exertion or in the context of respiratory illness, diaphragmatic fatigue can lead to inefficient breathing and shortness of breath. Rest and respiratory muscle training may help alleviate symptoms. - Secondary Complications:

Conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and obesity can impose additional strain on the diaphragm, leading to adaptive changes or dysfunction over time.

Understanding these conditions and their symptoms is critical for early diagnosis and effective management. Whether due to congenital defects, trauma, or neuromuscular disorders, diaphragm pathologies can significantly impact respiratory efficiency and overall quality of life. Early intervention and tailored treatments are essential to preserving diaphragmatic function and mitigating complications.

Diagnostic Approaches & Evaluation Tools

Accurate diagnosis of diaphragm disorders relies on a multifaceted approach that combines clinical evaluation, imaging techniques, and specialized tests. Early detection is crucial for effective treatment and the prevention of further complications. This section outlines the diagnostic methods used to assess diaphragm structure and function.

Clinical Examination and History

- Comprehensive History:

A detailed patient history is the cornerstone of diagnosis. Clinicians inquire about symptoms such as shortness of breath, orthopnea, chest pain, and persistent hiccups. Information regarding trauma, neuromuscular symptoms, and prior respiratory issues is also gathered. - Physical Examination:

Observing breathing patterns, inspecting chest movement, and palpating for tenderness help detect abnormal diaphragmatic motion. The presence of paradoxical or diminished movement can indicate paralysis or weakness.

Imaging Modalities

- Chest X-Ray:

X-rays provide a preliminary view of the diaphragm’s position and contour. Abnormal elevation, flattening, or discontinuities in the diaphragm may be visualized, offering clues to conditions such as hernias or eventration. - Ultrasonography:

Ultrasound is a non-invasive, real-time tool that measures diaphragmatic thickness and movement during breathing. It is especially useful in diagnosing paralysis or paresis, as it allows for dynamic assessment. - Fluoroscopy (“Sniff Test”):

Fluoroscopy enables visualization of diaphragmatic motion during rapid inhalation. In cases of paralysis, the affected side may exhibit paradoxical upward movement during inspiration. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT imaging provides high-resolution cross-sectional images of the diaphragm and surrounding structures. It is beneficial for identifying traumatic ruptures, hernias, and other structural abnormalities. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI offers detailed soft-tissue contrast without radiation exposure. It is particularly useful for evaluating diaphragmatic lesions, neuromuscular disorders, and subtle tissue changes.

Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT)

- Spirometry:

Spirometry measures lung volumes and capacities, which indirectly reflect diaphragmatic performance. Reduced inspiratory capacity or abnormal respiratory patterns can indicate diaphragmatic dysfunction. - Maximum Inspiratory Pressure (MIP) and Maximum Expiratory Pressure (MEP):

These tests assess the strength of respiratory muscles, including the diaphragm. Lower-than-normal pressures may signify muscle weakness or impaired neuromuscular transmission.

Electrophysiological Studies

- Electromyography (EMG):

Diaphragmatic EMG measures the electrical activity of the muscle during breathing. This test is particularly useful in diagnosing neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis and ALS, which affect diaphragmatic function. - Phrenic Nerve Conduction Studies:

These studies evaluate the integrity and function of the phrenic nerve. Abnormal conduction can point to nerve injury or neuropathy, which may underlie diaphragmatic paralysis.

Additional Diagnostic Tests

- Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) Analysis:

ABG testing helps assess respiratory efficiency by measuring oxygenation, carbon dioxide levels, and blood pH. Abnormal values can indicate compromised diaphragmatic function. - Lung Ultrasound and Elastography:

Emerging techniques such as elastography measure tissue stiffness and can provide additional insight into diaphragmatic health, particularly in patients with chronic respiratory conditions.

Combining these diagnostic approaches allows clinicians to obtain a comprehensive evaluation of diaphragm function and structure. The integration of clinical findings with advanced imaging and electrophysiological tests ensures that diaphragm disorders are accurately identified, paving the way for targeted treatment strategies.

Therapeutic Strategies & Interventions

The treatment of diaphragm disorders requires a tailored, multidisciplinary approach that considers the underlying cause, the severity of the condition, and the overall health of the patient. This section details the various therapeutic strategies, from non-invasive methods to advanced surgical interventions, designed to restore and enhance diaphragmatic function.

Non-Surgical Treatments

- Respiratory Therapy and Rehabilitation:

Respiratory therapy, including diaphragmatic breathing exercises and incentive spirometry, helps strengthen the diaphragm, improve lung capacity, and enhance overall breathing efficiency. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs often incorporate these exercises to boost respiratory muscle endurance. - Medications:

- Bronchodilators:

Medications that dilate the airways can reduce the workload on the diaphragm, particularly in patients with concurrent pulmonary conditions such as COPD. - Corticosteroids:

In cases of inflammation affecting the diaphragm or adjacent structures, corticosteroids may help reduce swelling and improve muscle function. - Neuromuscular Agents:

Drugs like pyridostigmine may be used in neuromuscular disorders (e.g., myasthenia gravis) to improve diaphragmatic strength by enhancing neuromuscular transmission. - Positive Pressure Ventilation:

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) techniques such as CPAP or BiPAP provide respiratory support in patients with diaphragmatic weakness or paralysis. These methods reduce the diaphragm’s workload and ensure adequate oxygenation.

Surgical Interventions

- Diaphragmatic Plication:

This surgical procedure involves folding and suturing the diaphragm to reduce its elevation and restore a more normal contour. It is particularly useful in cases of unilateral diaphragm paralysis or eventration, where the diaphragm is abnormally elevated. - Hernia Repair:

Traumatic or hiatal hernias that affect the diaphragm require surgical repair. Laparoscopic or open techniques are employed to reposition herniated organs and close defects in the diaphragm, thereby restoring its function. - Phrenic Nerve Pacing:

In select cases of diaphragmatic paralysis, especially when due to nerve dysfunction, electrical stimulation of the phrenic nerve can induce diaphragmatic contractions. This technique, known as phrenic nerve pacing, is used to improve respiratory function in patients who are not candidates for conventional ventilatory support. - Trauma Repair:

For diaphragmatic ruptures resulting from blunt or penetrating trauma, immediate surgical repair is essential. This may involve open thoracotomy or laparotomy to repair the torn diaphragm and reposition displaced organs.

Emerging and Regenerative Therapies

- Stem Cell Therapy:

Research into the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) aims to promote regeneration of damaged diaphragmatic tissue. While still experimental, early studies suggest that stem cell therapy may enhance muscle repair and improve diaphragmatic strength. - Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials:

Advances in tissue engineering have led to the development of scaffolds and biomaterials that can support diaphragmatic repair. These technologies hold promise for reconstructing damaged muscle tissue and restoring functional capacity. - Innovative Rehabilitation Techniques:

Emerging therapies, including virtual reality-assisted respiratory training and robotic-assisted rehabilitation, are being explored to optimize diaphragmatic function and enhance recovery in patients with neuromuscular disorders.

By integrating these diverse therapeutic approaches, clinicians can create personalized treatment plans that address both the underlying causes and the symptomatic manifestations of diaphragm disorders. The goal is to restore optimal diaphragmatic function, improve respiratory efficiency, and enhance the overall quality of life for affected patients.

Nutritional Support & Supplementation

Nutrition and supplementation play an important role in maintaining the health and function of the diaphragm. A balanced diet rich in essential vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients supports muscle strength, reduces inflammation, and promotes overall respiratory function. In this section, we explore dietary strategies and specific supplements that can help optimize diaphragmatic performance.

Essential Vitamins and Minerals

- Magnesium:

Magnesium is vital for muscle contraction and relaxation. Adequate magnesium levels help prevent muscle cramps and support the sustained performance of the diaphragm during respiration. - Vitamin D:

Beyond its role in bone health, vitamin D contributes to muscle function and immune regulation. Sufficient vitamin D levels may enhance respiratory muscle strength and reduce inflammation. - B Vitamins:

A group of B vitamins, including B6, B12, and folate, is essential for energy production and muscle metabolism. These vitamins support the overall function of the diaphragm by facilitating efficient cellular energy utilization. - Calcium:

Calcium plays a crucial role in muscle contraction and nerve transmission. Maintaining optimal calcium levels is important for the proper function of the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles.

Omega-3 and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

Found in fish oil, flaxseed, and walnuts, omega-3 fatty acids possess potent anti-inflammatory properties. They may help reduce inflammation in the respiratory muscles and promote overall muscle health. - Additional Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids:

These essential fats support cell membrane integrity and can help modulate inflammatory responses, contributing to improved diaphragmatic function.

Herbal and Natural Supplements

- Turmeric (Curcumin):

Curcumin, the active compound in turmeric, is well-known for its anti-inflammatory effects. It may help reduce inflammation in the diaphragm and improve muscle recovery following strenuous activity. - Ginger:

Ginger offers anti-inflammatory and antioxidant benefits that can contribute to improved respiratory function and reduced muscle soreness. - Boswellia Serrata:

This herbal extract is recognized for its ability to modulate inflammatory pathways, potentially benefiting patients with inflammatory diaphragm conditions.

Antioxidants and Enzymes

- Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10):

CoQ10 is essential for mitochondrial energy production and acts as a powerful antioxidant. It protects muscle cells, including those in the diaphragm, from oxidative stress and supports sustained muscle performance. - N-acetylcysteine (NAC):

NAC functions as a precursor to glutathione, a major intracellular antioxidant. It can help reduce oxidative damage and support the overall health of the diaphragm. - Other Antioxidants:

Polyphenols, flavonoids, and other natural antioxidants found in fruits, vegetables, and green tea contribute to reducing systemic oxidative stress, thereby supporting respiratory muscle function.

Hormonal Support

- DHEA (Dehydroepiandrosterone):

DHEA is a hormone that may promote muscle strength and reduce inflammatory responses. Supplementing with DHEA could potentially enhance diaphragmatic function in certain populations. - Melatonin:

While primarily known for its role in regulating sleep, melatonin also offers antioxidant benefits that help protect the diaphragm from oxidative stress and support overall muscle recovery.

By incorporating these nutritional strategies and targeted supplements into your daily regimen, you can provide essential support to your diaphragm. A diet rich in whole foods combined with specific supplementation can enhance respiratory muscle performance, reduce inflammation, and promote long-term respiratory health.

Lifestyle Practices for Optimizing Function

Maintaining a healthy diaphragm is not solely dependent on medical treatment or nutrition—it also involves adopting a series of proactive lifestyle habits. These practices can significantly enhance respiratory efficiency, reduce stress on the diaphragm, and improve overall health and well-being.

Regular Exercise and Respiratory Training

- Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises:

Practicing deep, controlled breathing techniques can strengthen the diaphragm and improve lung capacity. Techniques such as belly breathing and paced respiration help ensure the diaphragm is fully engaged during each breath. - Aerobic and Low-Impact Activities:

Regular physical activities such as walking, cycling, and swimming enhance cardiovascular health and promote efficient oxygen delivery to tissues. These exercises also support diaphragmatic endurance by improving overall respiratory function. - Core Strengthening:

Engaging in core-strengthening exercises, including Pilates and yoga, helps stabilize the diaphragm and improves posture. A strong core supports the diaphragm’s function and reduces the risk of respiratory fatigue.

Weight Management and Nutritional Balance

- Maintain a Healthy Weight:

Excess body weight places additional strain on the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles. Achieving and maintaining an optimal weight through balanced nutrition and regular exercise can alleviate this stress. - Balanced Diet:

A nutrient-dense diet that emphasizes whole grains, lean proteins, fruits, and vegetables provides the essential vitamins and minerals needed for muscle health, including that of the diaphragm. Proper nutrition supports energy production and muscle repair.

Avoidance of Harmful Substances

- Quit Smoking:

Smoking has a detrimental effect on respiratory muscles, including the diaphragm, by reducing oxygen delivery and increasing oxidative stress. Quitting smoking is one of the most beneficial steps for improving overall respiratory health. - Moderate Alcohol Consumption:

Excessive alcohol intake can impair muscle function and contribute to systemic inflammation. Moderation is key to preserving diaphragmatic and overall muscular health.

Stress Management and Rest

- Manage Stress:

Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which can negatively impact muscle health and exacerbate inflammation. Incorporating stress-reduction techniques such as meditation, mindfulness, and yoga can promote diaphragmatic relaxation and improve breathing efficiency. - Adequate Sleep:

Quality sleep is essential for the repair and regeneration of muscle tissue, including the diaphragm. Aim for 7–9 hours of sleep per night to support optimal respiratory function and overall health.

Posture and Ergonomics

- Maintain Proper Posture:

Good posture helps ensure that the diaphragm can move freely without restriction. Ergonomic adjustments at work and home, such as supportive chairs and proper desk height, can minimize unnecessary strain on the diaphragm. - Breathing Awareness:

Being mindful of your breathing patterns throughout the day can help ensure that you are using your diaphragm effectively. Regularly practicing proper breathing techniques can lead to long-term improvements in respiratory health.

By integrating these lifestyle practices into your daily routine, you can create a supportive environment for your diaphragm. The combination of regular exercise, balanced nutrition, stress management, and ergonomic habits not only improves diaphragmatic function but also enhances overall health and quality of life.

Reliable Resources & Further Reading

Staying informed about diaphragm health and respiratory function is essential for both patients and healthcare professionals. A variety of reputable resources provide in-depth insights, up-to-date research, and practical guidance on managing diaphragm-related conditions.

Recommended Books

- “Respiratory Physiology: The Essentials” by John B. West:

This text offers a comprehensive overview of respiratory physiology, including detailed discussions on diaphragm function and its role in breathing. - “The Respiratory System at a Glance” by Jeremy P.T. Ward and Jane Ward:

An accessible guide that breaks down the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system, emphasizing the diaphragm’s critical role. - “Principles of Pulmonary Medicine” by Steven E. Weinberger, Barbara A. Cockrill, and Jess Mandel:

This book provides extensive insights into respiratory diseases and the various conditions that can affect diaphragm function.

Academic Journals

- American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine:

A leading publication featuring the latest research in respiratory health, including studies on diaphragm mechanics and treatment strategies. - Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology:

This journal focuses on the underlying physiological mechanisms of respiration, providing in-depth analyses of diaphragmatic function and neuromuscular control.

Digital Tools and Mobile Apps

- Breathe2Relax:

A mobile app that offers guided breathing exercises to improve diaphragmatic breathing and reduce stress. - MyFitnessPal:

An app that tracks nutrition and physical activity, promoting a balanced lifestyle that supports respiratory and overall muscle health. - Headspace:

A mindfulness and meditation app designed to help manage stress, indirectly benefiting diaphragmatic function through relaxation techniques.

These trusted resources offer valuable insights and practical tools for those looking to deepen their understanding of diaphragm health and optimize respiratory function. Whether you are a patient managing a respiratory condition or a healthcare professional seeking the latest research, these materials provide reliable, up-to-date information.

Frequently Asked Questions About Diaphragm

What is the diaphragm and why is it important?

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscular partition that separates the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It is the primary muscle of respiration, essential for breathing, supporting core stability, and facilitating functions such as venous return and abdominal pressure regulation.

How does the diaphragm contribute to breathing?

During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts and flattens, increasing thoracic cavity volume and creating a negative pressure that draws air into the lungs. During exhalation, it relaxes, allowing the lungs to expel air. This rhythmic movement is crucial for effective gas exchange.

What conditions can affect diaphragm function?

Diaphragm function can be compromised by various conditions such as diaphragmatic hernias, paralysis or paresis, traumatic injuries, and neuromuscular disorders like myasthenia gravis and ALS. These conditions can lead to respiratory distress and reduced lung capacity.

How is diaphragm dysfunction diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves clinical evaluation, patient history, imaging techniques such as chest X-rays, ultrasound, fluoroscopy, CT or MRI scans, pulmonary function tests, and sometimes electromyography (EMG) to assess muscle activity and phrenic nerve conduction.

What lifestyle changes can support diaphragm health?

Maintaining diaphragm health involves regular diaphragmatic breathing exercises, physical activity, a balanced diet, stress management, proper posture, and avoiding harmful habits such as smoking. These measures help strengthen the diaphragm and promote efficient respiratory function.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social media platform to help spread awareness about diaphragm health and respiratory wellness.