What is retinal detachment?

Retinal detachment is a serious and potentially blinding ocular condition in which the retina, a thin layer of tissue at the back of the eye, separates from the surrounding supportive tissue. The retina detects light and sends visual signals to the brain via the optic nerve. When the retina detaches, it no longer functions properly, posing a significant risk of vision loss if not treated immediately.

Anatomy of the Retina

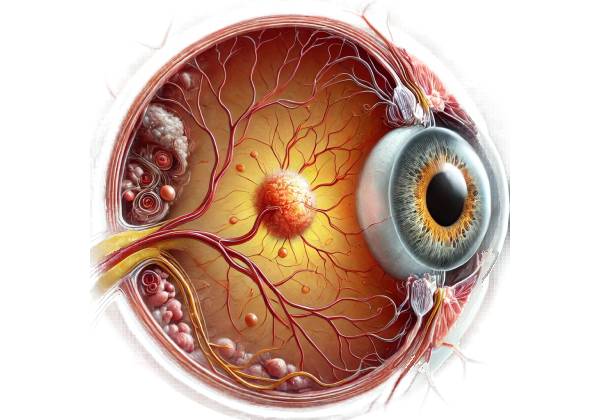

To understand retinal detachment, you must first understand the retina’s anatomy and role in vision. The retina is made up of multiple layers, the most important of which are photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) that capture light and convert it into electrical signals. These signals are then processed by other retinal neurons and transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve, where they are translated into visual images.

The retina is connected to the underlying choroid, a layer rich in blood vessels that supplies the retina with oxygen and nutrients. Between the retina and the choroid is a thin layer of cells known as the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which is critical for retinal health and function. The RPE nourishes the photoreceptors, eliminates waste products, and forms a barrier to protect the retina from harmful substances.

Types of Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment can take many different forms, each with its own set of causes and risk factors. The three main types of retinal detachments are:

- Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment: The most common type of retinal detachment, it occurs when a tear or break in the retina allows fluid from the vitreous cavity—the gel-like substance that fills the eye—to seep beneath the retina. The fluid accumulation causes the retina to lift away from the choroid. The most common cause of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is age-related changes in the vitreous, which results in posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). PVD may cause traction on the retina, resulting in a tear or hole. When the retina tears, the vitreous fluid can pass through the opening, resulting in detachment.

- Tractional Retinal Detachment: When scar tissue or other fibrous tissue on the retina’s surface contracts, it pulls the retina away from the underlying tissues. Tractional retinal detachment is most commonly associated with proliferative diabetic retinopathy, a diabetes complication in which abnormal blood vessels develop on the retina and eventually form scar tissue. Tractional detachment is less common than rhegmatogenous detachment, but it can be more difficult to treat because it involves scar tissue.

- Exudative Retinal Detachment: Exudative, or serous, retinal detachment occurs when fluid accumulates beneath the retina without causing a retinal tear or break. Underlying conditions that cause fluid leakage from blood vessels in the retina or choroid are the most common causes of this type of detachment. These conditions include inflammatory disorders like uveitis, central serous chorioretinopathy, and cancers like choroidal melanoma. Exudative detachment can also occur in systemic diseases that affect the vascular system, such as hypertension and preeclampsia.

Risk Factors for Retinal Detachment

Several risk factors increase the chances of developing retinal detachment. Understanding these risk factors can assist in identifying individuals who may be at a higher risk and require additional monitoring.

- Age: The risk of retinal detachment rises with age, especially among those over the age of 50. As the eye ages, the vitreous becomes more liquid and loses its gel-like consistency. This increases the likelihood of posterior vitreous detachment, which can result in retinal tears and detachment.

- Myopia (Nearsightedness): High myopia increases the risk of retinal detachment. In myopic eyes, the eyeball is longer than usual, putting additional strain on the retina and increasing the likelihood of tears or holes forming. Myopia also increases the risk of posterior vitreous detachment, which contributes to the overall risk of retinal detachment.

- Previous Eye Surgery: People who have had eye surgeries, particularly cataract surgery, are at a higher risk of retinal detachments. Cataract surgery removes the eye’s natural lens, which can change the vitreous and increase the risk of posterior vitreous detachment. Furthermore, any surgical trauma to the eye can weaken the retina, making it susceptible to detachment.

- Family History: A family history of retinal detachment may increase an individual’s risk, indicating a genetic predisposition to the condition. Stickler syndrome and Marfan syndrome are examples of inherited conditions that increase the risk of retinal detachments.

- Trauma: Blunt or penetrating trauma to the eye can cause retinal detachment. Trauma can cause retinal tears or vitreous hemorrhage, which causes traction on the retina.

- Previous Retinal Detachment: People who have had retinal detachment in one eye are more likely to develop it in the other. The risk is especially high if the underlying cause, such as myopia or vitreous degeneration, affects both eyes.

Symptoms of Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachment is a medical emergency, and identifying the symptoms is critical for timely treatment. The symptoms of retinal detachment can vary depending on the extent and location of the detachment, but generally include:

- Sudden Onset of Floaters: Floaters are small, dark shapes that appear to move across the field of vision. They occur when clumps of cells or proteins in the vitreous cast shadows on the retina. While floaters are common and often harmless, a sudden increase in their number or size may indicate retinal detachment.

- Flashes of Light (Photopsia): Photopsia is defined as brief flashes or streaks of light in the peripheral vision that are often described as resembling lightning or sparks. These flashes occur when the retina is tugged or pulled, which can happen with posterior vitreous detachment or a retinal tear.

- Shadow or Curtain Over Vision: As the retina detaches, patients may notice a shadow or curtain-like effect forming over their vision. This shadow usually begins in the peripheral vision and moves toward the center as the detachment worsens. The shadow’s location corresponds to the detaching retina.

- Blurred or Distorted Vision: If the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision, is involved in the detachment, patients may notice a sudden decrease in visual acuity, blurring, or distortion of vision. Central vision loss is particularly concerning because it can cause significant and possibly permanent visual impairment.

- Vision Loss: In advanced cases of retinal detachment, particularly if left untreated, the affected eye may lose its vision completely. This occurs when the entire retina detaches and becomes unable to function, resulting in blindness in that eye.

Complications Of Retinal Detachment

If not treated promptly, retinal detachment can result in severe complications, including:

- Permanent Vision Loss: The most serious side effect of retinal detachment is permanent vision loss. The extent of vision loss is determined by the amount of retina detached and the duration of the detachment. Prompt treatment can frequently prevent total blindness, but some vision loss is possible, particularly if the macula is involved.

- Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy (PVR) is a condition in which scar tissue forms on the surface of the retina following a detachment, causing traction and recurrent detachment. PVR is a serious complication that can make retinal detachment more difficult to treat and necessitate more complex surgical procedures.

- Recurrent Retinal Detachment: Even with successful treatment, there is a risk of recurrent detachment, especially if the underlying causes, such as myopia or vitreous degeneration, persist. Regular follow-up is required to check for signs of recurrence.

- Cataract Formation: Cataracts, or clouding of the eye’s lens, can occur as a side effect of retinal detachment surgery or as a result of eye trauma. Cataract formation can worsen vision and may necessitate surgical removal.

Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that requires immediate diagnosis and treatment to save vision. Understanding the risk factors, symptoms, and potential complications of retinal detachment is critical for early diagnosis and treatment.

Accurate Diagnosis of Retinal Detachment

Clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and specialized tests are used to determine the extent and location of the retinal detachment. Accurate and timely diagnosis is critical for determining the best treatment option and avoiding permanent vision loss.

Clinical Evaluation

The first step in diagnosing retinal detachment is to conduct a thorough clinical evaluation, which includes a detailed patient history and an eye examination. The clinician will inquire about the onset, duration, and nature of symptoms, such as floaters, flashes of light, or shadows in the field of vision. The patient’s medical history, including any previous eye conditions, surgeries, or trauma, plays an important role in guiding the diagnostic process.

Fundus Examination

A fundus examination, also known as an ophthalmoscopy, is a valuable diagnostic tool for visualizing the retina and detecting retinal detachment. During this examination, the clinician examines the interior surface of the eye with an ophthalmoscope or slit lamp equipped with a specialized lens, which includes the retina, optic disc, and retinal blood vessels.

In cases of retinal detachment, the retina may appear elevated and wrinkled, especially where it has detached from the underlying layers. The clinician may also see any retinal tears or holes that caused the detachment. The detached retina in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment may appear corrugated or “billowing” as a result of fluid accumulation beneath it. If the detachment affects the macula, the central part of the retina, it will be carefully evaluated because it has serious consequences for the visual prognosis.

Indirect Ophthalmoscopy

Indirect ophthalmoscopy is another useful technique for diagnosing retinal detachment. This method provides a wide field of view, allowing the clinician to more thoroughly examine the peripheral retina, which is critical because retinal tears and detachments frequently begin in the peripheral areas. The procedure uses a head-mounted light source and a handheld lens to visualize the retina in three dimensions. This technique is especially useful for determining the extent of the detachment and detecting multiple breaks or tears in the retina.

Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT)

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that produces high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina. OCT is especially useful when the diagnosis is uncertain or subtle retinal changes need to be evaluated. OCT can detect minor detachments, macular involvement, and the presence of subretinal fluid that standard ophthalmoscopy may miss.

In cases of macula-off retinal detachment, OCT can help assess the macula’s integrity and predict visual outcomes following surgery. It can also detect other retinal conditions that could be causing the detachment, such as epiretinal membranes or vitreomacular traction.

B-scan ultrasonography

B-scan ultrasonography is an important diagnostic tool when direct retinal visualization is difficult, such as when dense cataracts, vitreous hemorrhage, or other media opacities obscure the view. B-scan ultrasound generates real-time cross-sectional images of the eye, allowing the clinician to see the detached retina, locate any retinal tears, and determine the extent of vitreous traction or hemorrhage. This imaging technique is especially useful for confirming the diagnosis of retinal detachment when other methods are ineffective.

Fundal Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) is a technique for assessing the retinal vasculature that involves injecting a fluorescent dye into the bloodstream and taking a series of photographs as it circulates through the retinal blood vessels. Although FFA is not typically used as a first-line diagnostic tool for retinal detachment, it can be useful in cases where there are concerns about associated vascular abnormalities or in distinguishing retinal detachment from other conditions such as central serous chorioretinopathy or retinal vein occlusion.

Electroretinography (ERG)

Electroretinography (ERG) measures the retina’s electrical activity in response to light stimuli. While ERG is not widely used in the routine diagnosis of retinal detachment, it can provide useful information about the retina’s functional status, especially when retinal detachment is suspected but not clearly visible on imaging. ERG can help distinguish between retinal detachment and other conditions that cause retinal dysfunction, such as retinal dystrophy.

Differential Diagnosis

It is critical to distinguish retinal detachment from other ocular conditions that may produce similar symptoms, such as floaters, flashes of light, or vision loss. These conditions include the following:

Posterior Vitreous Detachment (PVD) is a common age-related condition in which the vitreous gel separates from the retina, resulting in floaters and flashes. Unlike retinal detachment, PVD does not cause the retina to separate from the underlying tissue.

- Vitreous Hemorrhage: Bleeding into the vitreous cavity can reduce vision and cause floaters, but the retina remains attached. B-scan ultrasonography can help differentiate between vitreous hemorrhage and retinal detachment.

- Retinal Vein Occlusion: A blockage in the retinal veins causes sudden vision loss and swelling, but the retina remains attached. FFA can help distinguish between retinal vein occlusion and retinal detachment.

Effective Treatments for Retinal Detachment

To avoid permanent vision loss, retinal detachment requires prompt intervention. The type, location, and severity of the detachment, as well as the patient’s overall health and visual needs, determine the appropriate treatment approach. The main goal of treatment is to reattach the retina to the underlying tissues, restore normal retinal function, and prevent recurrence. The following are the primary methods for managing retinal detachment:

Laser Photocoagulation & Cryopexy

When a retinal tear or small detachment is detected early, before significant detachment occurs, laser photocoagulation or cryopexy may be used to prevent further progression.

- Laser Photocoagulation: This technique involves using a laser to create small burns around the retinal tear, forming a scar that seals the edges of the tear and prevents fluid from passing through and causing further detachments. Laser photocoagulation is frequently performed as an outpatient procedure and is extremely effective at preventing retinal detachment progression.

- Cryopexy: Cryopexy is the process of applying intense cold to the area around the retinal tear with a cryoprobe. This freezing process leaves a scar that seals the tear and aids in the reattachment of the retina. Cryopexy is frequently used in conjunction with other surgical procedures for larger detachments.

Pneumatic Retinopexy

Pneumatic retinopexy is a minimally invasive procedure used to treat certain types of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, particularly those that are simple and affect the upper half of the retina. The procedure involves injecting a small gas bubble into the eye’s vitreous cavity. The patient is then positioned so that the gas bubble floats to the location of the retinal tear, pressing the retina back against the underlying tissues. Once the retina has been reattached, the tear is sealed with laser photocoagulation or cryopexy to prevent recurrence.

Pneumatic retinopexy is typically performed in an outpatient setting and is less invasive than other surgical procedures. However, careful patient cooperation is required, as the patient must maintain a specific head position for several days to keep the gas bubble in contact with the retinal tear.

Scleral Buckling

Scleral buckling is a more invasive surgical procedure for treating retinal detachment, especially when there are multiple tears or significant traction on the retina. The procedure entails wrapping a silicone band, or buckle, around the outside of the eye (sclera) to indent the eye wall and bring the retina back into contact with the surrounding tissue.

The buckle is permanently attached and works by relieving traction on the retina and narrowing the gap between the retina and the sclera. Scleral buckling is frequently combined with other procedures, such as laser photocoagulation or cryopexy, to keep the retina attached after surgery. While effective, scleral buckling is more invasive than other procedures and has a higher risk of complications such as infection, bleeding, or changes in refractive error.

Vitrectomy

Vitrectomy is a surgical procedure used to treat more complex cases of retinal detachment, such as those caused by tractional forces or when the vitreous humor is clogged with blood or other debris. A vitrectomy involves the surgeon removing the vitreous gel from the eye and replacing it with a clear fluid, gas bubble, or silicone oil. This removal allows the surgeon to gain better access to the retina and perform repairs such as scar tissue removal, retinal tear sealing, and retinal reattachment.

Vitrectomy is especially useful in cases of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR), a condition in which scar tissue on the retina causes recurrent detachment. The procedure is usually performed under local or general anesthesia, and there is a recovery period during which the patient may need to hold a specific head position if a gas bubble is used.

Post-operative Care and Monitoring

Following retinal detachment surgery, patients require close post-operative care and monitoring to ensure the retina remains attached and to manage any complications. This care includes the use of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory eye drops to prevent infection and inflammation. To avoid eye strain, patients should avoid strenuous activities and heavy lifting during their recovery period.

Regular follow-up appointments are required to monitor the healing process and identify any signs of recurrent detachment or other complications. In some cases, additional surgeries may be required to treat complications like cataract formation, PVR, or persistent retinal tears.

Long-Term Management

Even after successful treatment, patients with a history of retinal detachment need long-term monitoring to avoid recurrence and manage any underlying risk factors, such as high myopia or diabetes. Regular eye exams are essential for detecting new retinal tears or detachments in the other eye. Patients are also informed about the warning signs of retinal detachment, such as the sudden appearance of floaters, flashes, or vision changes, and are advised to seek immediate medical attention if these symptoms occur.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books.

- “Ryan’s Retina” by Andrew P. Schachat, Charles P. Wilkinson, and David R. Hinton – This comprehensive textbook covers the diagnosis and treatment of retinal diseases, including retinal detachment, and provides detailed information for both clinicians and patients.

- “Retina: Medical and Surgical Management” by Stephen J. Ryan – A valuable resource for understanding the complexities of retinal detachment and its various treatment options, featuring contributions from leading experts in the field.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) – The AAO offers numerous resources, guidelines, and patient education materials on retinal detachment, including diagnosis, treatment options, and post-operative care.

- National Eye Institute (NEI) – The NEI provides extensive information on eye health, including research and resources on retinal detachment, as well as advice on how to manage and prevent the condition.