The abdomen is a vital region of the human body that plays a central role in digestion, metabolism, and overall health. Nestled between the chest and pelvis, this complex cavity houses essential organs such as the stomach, liver, intestines, and pancreas. Its intricate structure not only supports food processing and nutrient absorption but also serves as a key component in immune function and detoxification. Understanding the abdomen’s anatomy and functions is critical for identifying potential health issues and implementing effective treatments. Explore this guide to discover in-depth insights, modern diagnostic approaches, and lifestyle tips that support optimal abdominal health.

Table of Contents

- Detailed Abdominal Blueprint

- Primary Abdominal Functions

- Abdominal Health Challenges

- Advanced Diagnostic Strategies

- Modern Abdominal Therapies

- Nutritional Support & Supplements

- Optimizing Abdominal Wellness

- Credible Health Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

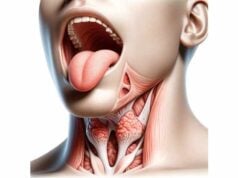

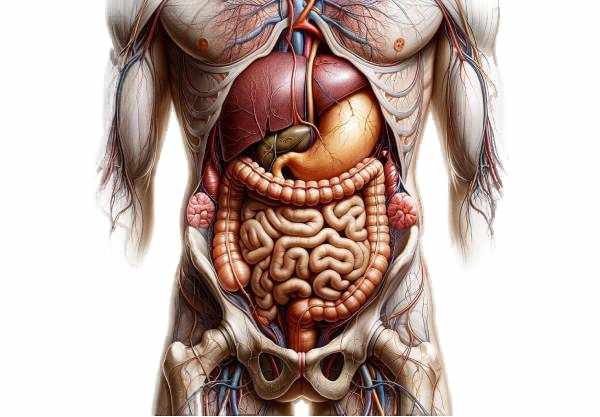

Detailed Abdominal Blueprint

The human abdomen is a marvel of biological architecture, characterized by layers of muscles, connective tissues, and a myriad of vital organs. This section delves into the structural intricacies of the abdominal cavity, offering a comprehensive look at its various components.

Abdominal Regions and Landmarks

The abdomen is customarily divided into distinct regions for clinical and anatomical clarity. These divisions aid in diagnostic precision and treatment planning. Medical professionals often refer to either a quadrant system or a nine-region layout:

- Right Hypochondriac Area: Home to a significant portion of the liver and gallbladder, this area is crucial for bile production and detoxification.

- Epigastric Zone: Centrally located, it houses parts of the stomach and the pancreas, making it a focal point for digestive enzyme secretion.

- Left Hypochondriac Sector: Encompasses the spleen and portions of the stomach, playing a role in immune responses.

- Lumbar and Iliac Regions: These lateral and lower sections include parts of the colon, kidneys, and in some cases, the appendix, all of which contribute to waste elimination and hormonal balance.

- Umbilical Region: Centrally positioned, it features sections of the small and large intestines, critical for nutrient absorption and fluid regulation.

This segmentation not only assists clinicians during physical examinations but also directs imaging and surgical procedures to precise areas of concern.

The Layers of the Abdominal Wall

Encasing the internal organs, the abdominal wall is composed of several layers that provide protection and structural support:

- Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue: The outermost layer serves as the first barrier against external elements, while underlying fat provides insulation.

- Muscular Layers: Key muscles such as the rectus abdominis, external and internal obliques, and transversus abdominis support posture, enable movement, and assist in the breathing process.

- Fascial Planes: These connective tissue layers compartmentalize the muscles and help distribute mechanical stress evenly, crucial for maintaining core stability.

An understanding of these layers is essential, especially when considering surgical incisions or treating traumatic injuries.

The Peritoneum and Its Role

The peritoneum is a smooth, serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity, performing vital functions such as lubrication and infection prevention. It is divided into:

- Parietal Peritoneum: This layer lines the interior of the abdominal wall, providing a frictionless interface for movement.

- Visceral Peritoneum: It covers the organs themselves, offering protection and facilitating the exchange of nutrients and fluids.

- Peritoneal Cavity: The potential space between these two layers is filled with lubricating fluid, ensuring that the organs glide smoothly against one another during movement.

The peritoneum’s dynamic role is central to abdominal health, affecting both mechanical protection and the spread of infections.

Major Internal Organs

Within this intricately structured cavity reside the organs responsible for critical physiological functions:

- Stomach: A muscular, expandable organ that initiates the digestive process through mechanical churning and chemical breakdown of food.

- Liver: The body’s largest internal organ, the liver is pivotal for detoxification, protein synthesis, and bile production, which aids in fat digestion.

- Gallbladder: Acting as a storage reservoir, it concentrates bile produced by the liver before its release into the small intestine.

- Pancreas: This dual-function gland contributes digestive enzymes for food breakdown and hormones like insulin to regulate blood sugar levels.

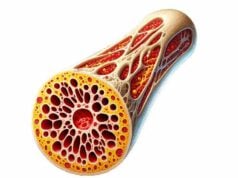

- Intestines: Divided into the small and large intestines, they are responsible for nutrient absorption and the elimination of waste products.

- Spleen: An integral part of the lymphatic system, it filters blood and plays a key role in immune surveillance and response.

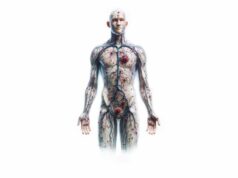

Vascular and Neural Networks

The abdomen is richly supplied by an extensive network of blood vessels and nerves:

- Arterial Supply: The abdominal aorta and its branches, including the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric arteries, ensure that each organ receives the oxygen and nutrients it needs.

- Venous Drainage: Complementing the arterial system, the portal vein collects blood from the digestive organs and directs it to the liver for detoxification.

- Nervous Innervation: Both the autonomic and somatic nervous systems innervate the abdominal region. The autonomic nerves regulate involuntary functions like peristalsis, while the somatic nerves manage sensation and voluntary muscle movements.

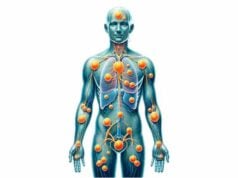

- Lymphatic System: Lymph nodes scattered throughout the abdomen filter pathogens and waste products, while the thoracic duct channels lymph back into the bloodstream, maintaining fluid balance and immune function.

The synergy among these systems is crucial for maintaining homeostasis and ensuring the abdomen functions optimally.

Primary Abdominal Functions

The abdomen is a powerhouse of physiological processes. Beyond its anatomical complexity, its primary functions drive essential activities such as digestion, metabolism, immune defense, and structural support.

Digestive Processes

Digestion is the cornerstone of abdominal function. It involves a coordinated sequence of mechanical and chemical actions:

- Mechanical Breakdown: The stomach’s muscular contractions physically reduce food size, mixing it with digestive juices to form chyme.

- Enzymatic Degradation: The pancreas secretes enzymes like amylase, proteases, and lipases, which break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Concurrently, bile from the liver emulsifies fats to enhance enzymatic efficiency.

- Absorption: The small intestine, lined with millions of tiny villi and microvilli, maximizes the surface area available for nutrient absorption, ensuring that vitamins, minerals, and amino acids enter the bloodstream.

- Water Reabsorption: The large intestine plays a vital role in reclaiming water and electrolytes from indigestible food matter, thereby consolidating waste for excretion.

Each step in the digestive process is finely tuned and interdependent, illustrating the sophisticated coordination required for effective nutrient assimilation.

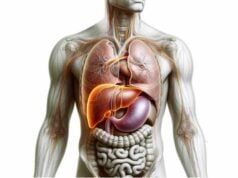

Metabolic Regulation

The abdomen also plays a central role in metabolism, managing the conversion of food into energy and the regulation of blood sugar levels:

- Liver Metabolism: The liver is instrumental in processing nutrients absorbed from the digestive tract. It stores glycogen, synthesizes vital proteins, and detoxifies harmful substances.

- Hormonal Balance: The pancreas not only aids in digestion but also secretes hormones such as insulin and glucagon, which are essential for maintaining glucose homeostasis. These hormones work in tandem to balance energy production and storage.

- Bile Production: Beyond aiding digestion, bile helps in the regulation of cholesterol levels and the removal of metabolic waste, further highlighting the liver’s multifaceted role in metabolic health.

This intricate metabolic network ensures that the body maintains energy equilibrium and adapts to varying nutritional demands.

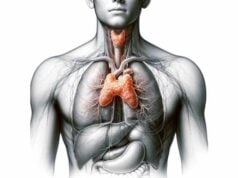

Immune and Protective Functions

The abdomen is a frontline defense in the immune system:

- Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT): Embedded within the walls of the intestines, GALT generates a substantial portion of the body’s immune cells. This system monitors and responds to pathogens introduced via food.

- Splenic Filtration: The spleen acts as a blood filter, removing old or damaged cells and initiating immune responses against infections.

- Barrier Function: The peritoneum and the intestinal mucosa form critical barriers that prevent the invasion of harmful microorganisms while permitting nutrient absorption.

Together, these mechanisms create a robust defense system that safeguards the body against infections and inflammatory conditions.

Structural and Supportive Roles

The abdomen not only houses vital organs but also contributes to overall body mechanics:

- Muscular Support: The abdominal muscles provide core stability, enabling smooth movements and protecting internal organs from mechanical shocks.

- Respiratory Assistance: The diaphragm, which forms the superior boundary of the abdominal cavity, plays a crucial role in breathing. Its rhythmic contractions facilitate lung expansion and efficient oxygen exchange.

- Temperature Regulation: Blood flowing through the abdominal organs helps dissipate heat, ensuring a stable internal environment conducive to enzymatic and metabolic reactions.

- Hormone Secretion: Beyond digestion, the gastrointestinal tract produces hormones that influence appetite, motility, and satiety, thereby integrating abdominal function with overall bodily regulation.

The convergence of these diverse roles underscores the abdomen’s indispensability in sustaining life and maintaining health.

Abdominal Health Challenges

A wide spectrum of conditions can affect the abdomen, ranging from benign functional disorders to severe, life-threatening diseases. Recognizing these challenges is key to early intervention and effective treatment.

Digestive System Disorders

Digestive disorders often manifest through a variety of symptoms such as pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits. Common conditions include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): This condition results from the backflow of stomach acid into the esophagus, leading to heartburn, regurgitation, and chronic discomfort. Lifestyle modifications and medications, including proton pump inhibitors, are often recommended.

- Peptic Ulcer Disease: Sores that develop on the stomach or duodenal lining, typically due to Helicobacter pylori infection or prolonged NSAID use. Patients may experience burning pain, nausea, and bloating.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A functional disorder characterized by abdominal pain, cramping, and irregular bowel movements. Stress management, dietary adjustments, and medications can help alleviate symptoms.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Encompassing Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, IBD involves chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract, often accompanied by severe diarrhea, pain, and fatigue. Treatment may include anti-inflammatory drugs, immunosuppressants, or surgery.

Hepatic and Biliary Conditions

The liver and gallbladder are susceptible to a range of diseases that compromise their functions:

- Hepatitis: Inflammation of the liver, most commonly caused by viral infections. Symptoms include jaundice, fatigue, and abdominal pain. Vaccinations and antiviral medications are crucial in prevention and treatment.

- Cirrhosis: A progressive scarring of liver tissue resulting from chronic liver injury, often due to alcoholism or viral hepatitis. Clinical features include fluid retention, jaundice, and impaired coagulation.

- Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD): Fat accumulation in the liver, frequently associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome. Lifestyle modifications, particularly weight loss and exercise, are primary treatment strategies.

Pancreatic and Other Disorders

The pancreas and adjacent organs are equally vulnerable to pathological changes:

- Pancreatitis: Inflammation of the pancreas, either acute or chronic, often triggered by gallstones or excessive alcohol consumption. It is marked by severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, frequently requiring hospitalization and supportive care.

- Pancreatic Cancer: One of the most aggressive forms of cancer, pancreatic malignancies are characterized by late presentation and poor prognosis. Symptoms may include weight loss, jaundice, and persistent pain.

- Appendicitis and Hernias: Appendicitis involves inflammation of the appendix, often necessitating surgical removal, while hernias result from the protrusion of internal organs through a defect in the abdominal wall. Both conditions require prompt medical evaluation.

Additional Abdominal Ailments

Other conditions that impact the abdominal region include:

- Gallstones: Hardened deposits that form within the gallbladder, often causing severe pain and potential infections. Management may range from dietary changes to surgical intervention.

- Diverticulitis: Inflammation or infection of small pouches (diverticula) that can form in the colon, leading to abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.

- Bowel Obstructions and Perforations: These acute conditions require immediate medical attention, as they can rapidly progress to life-threatening scenarios if not treated promptly.

Understanding the myriad of abdominal health challenges is the first step toward effective prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, emphasizing the need for regular medical evaluations and healthy lifestyle choices.

Advanced Diagnostic Strategies

Modern medicine has developed an array of diagnostic tools to investigate abdominal complaints accurately. These methods enable clinicians to pinpoint the underlying causes of abdominal symptoms and tailor treatments accordingly.

Imaging Modalities

Non-invasive imaging is central to abdominal diagnosis:

- Ultrasound Imaging: A first-line, radiation-free technique that employs high-frequency sound waves to produce real-time images of abdominal organs. It is particularly effective for evaluating the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, and vascular structures.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scans: Offering detailed cross-sectional images, CT scans are invaluable for detecting tumors, abscesses, and traumatic injuries. With CT angiography, clinicians can assess vascular anomalies and plan surgical interventions.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Utilizing magnetic fields and radio waves, MRI produces high-resolution images of soft tissues. Specialized protocols, such as MRCP (Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography), provide intricate details of the bile and pancreatic ducts.

- X-rays: Although less detailed than other modalities, plain radiography remains useful in emergency settings to identify obstructions, perforations, or the presence of foreign bodies.

Laboratory Assessments

Biochemical tests offer insights into organ function and systemic health:

- Blood Panels: Comprehensive metabolic profiles, liver function tests (LFTs), and pancreatic enzyme assays help assess the functional status of abdominal organs. Elevated enzyme levels or abnormal markers can signal inflammation, infection, or tissue damage.

- Stool Analysis: Stool tests, including occult blood and pathogen cultures, are essential in detecting gastrointestinal bleeding, malabsorption syndromes, and infectious processes.

Endoscopic Techniques

Direct visualization via endoscopy allows for both diagnosis and treatment:

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD): This procedure examines the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, permitting biopsy and direct assessment of ulcers, inflammation, or tumors.

- Colonoscopy: A comprehensive evaluation of the colon and rectum, colonoscopy is instrumental in detecting polyps, colorectal cancer, and inflammatory conditions. It also enables therapeutic interventions, such as polyp removal.

- ERCP (Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography): Combining endoscopy with fluoroscopy, ERCP is employed to diagnose and treat obstructions or anomalies in the bile and pancreatic ducts, including stone removal and stent placements.

Functional and Molecular Diagnostics

Emerging diagnostic techniques are refining our understanding of abdominal diseases:

- Manometry and Motility Studies: These tests measure the pressure and movement within the gastrointestinal tract, aiding in the diagnosis of motility disorders.

- Capsule Endoscopy: A minimally invasive procedure in which the patient swallows a small camera capsule, enabling detailed imaging of the small intestine—a region traditionally challenging to examine.

- Genetic and Molecular Testing: Advanced assays, including PCR and next-generation sequencing, are increasingly used to detect genetic predispositions and molecular markers of malignancy, facilitating personalized treatment plans.

Collectively, these diagnostic strategies form a comprehensive approach that enhances early detection and guides effective management of abdominal conditions.

Modern Abdominal Therapies

Effective treatment of abdominal disorders demands a tailored approach, incorporating a spectrum of medical, surgical, and emerging therapeutic strategies. Here, we explore the modern interventions available for managing abdominal ailments.

Conventional Medical Treatments

Pharmacologic therapies remain the cornerstone of treatment for many abdominal conditions:

- Acid Suppressants and Anti-inflammatory Agents: Medications such as proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists alleviate conditions like GERD and peptic ulcers by reducing gastric acid secretion.

- Antibiotics and Antivirals: Targeted antimicrobial therapies address infections including Helicobacter pylori-induced ulcers and viral hepatitis.

- Immunomodulators and Corticosteroids: In cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and autoimmune-mediated liver damage, these drugs help mitigate chronic inflammation and immune overactivity.

- Enzyme Replacement Therapy: For patients with pancreatic insufficiency, supplemental digestive enzymes improve nutrient absorption and relieve gastrointestinal symptoms.

Surgical Interventions

Surgical procedures offer definitive solutions when conservative measures fall short:

- Minimally Invasive Laparoscopy: Techniques such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, appendectomy, and hernia repair minimize trauma, reduce recovery times, and lower complication rates compared to open surgery.

- Resection Surgeries: For advanced malignancies or severe tissue damage, surgical resection of affected segments (e.g., colectomy, hepatectomy) may be required, often followed by reconstructive procedures or stoma formation.

- Transplant Procedures: In end-stage liver disease or acute hepatic failure, liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment, supported by advances in immunosuppressive therapy and post-operative care.

Endoscopic and Interventional Therapies

Minimally invasive endoscopic procedures have revolutionized the treatment landscape:

- Endoscopic Resection: Techniques such as Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) and Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD) allow for the removal of superficial tumors and precancerous lesions without the need for open surgery.

- Stent Placement and Dilation: Endoscopic stenting provides relief in obstructive conditions of the bile or pancreatic ducts, ensuring continued organ function while bypassing the blockage.

Innovative and Targeted Treatments

The advent of precision medicine is paving the way for novel treatment modalities:

- Biologic Therapies: Monoclonal antibodies targeting specific inflammatory pathways have shown remarkable efficacy in conditions like IBD, offering a more focused treatment with fewer systemic side effects.

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): By restoring the balance of gut bacteria, FMT has emerged as an effective treatment for recurrent Clostridium difficile infections and other dysbiosis-related disorders.

- Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine: Investigational therapies using stem cells aim to repair damaged liver tissue or rejuvenate the intestinal lining, holding promise for reversing chronic disease processes.

- Minimally Invasive Ablative Techniques: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and microwave ablation (MWA) offer targeted destruction of malignant tissues with minimal collateral damage, particularly in liver and pancreatic cancers.

Modern abdominal therapies are continually evolving, offering patients a wider array of treatment options that are less invasive, more targeted, and tailored to individual genetic and physiological profiles.

Nutritional Support & Supplements

A balanced diet and appropriate supplementation are crucial for maintaining abdominal health. Nutritional support not only aids in digestion and metabolism but also plays a significant role in preventing and managing various abdominal conditions.

Essential Nutrients and Vitamins

Proper nutrition forms the foundation of abdominal wellness:

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Found in fish oils and certain plant sources, these fats exhibit potent anti-inflammatory properties that can alleviate inflammatory conditions within the digestive tract.

- Vitamin D: Crucial for immune regulation and cellular health, vitamin D deficiencies have been linked to an increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease and other chronic conditions.

- Vitamin C and E: As powerful antioxidants, these vitamins help neutralize free radicals, reducing oxidative stress and supporting overall cellular integrity.

Herbal and Natural Supplements

Natural compounds offer an adjunctive approach to maintaining gastrointestinal health:

- Turmeric (Curcumin): Known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, turmeric can help reduce inflammation in conditions like IBD and support liver function.

- Ginger: Traditionally used to ease nausea and improve digestion, ginger supplements may provide relief for those suffering from gastrointestinal discomfort.

- Probiotics: Beneficial bacteria, when taken as supplements, can help restore gut flora balance, enhance digestion, and boost the immune system.

Digestive Enzymes and Antioxidants

Enzyme and antioxidant supplementation can further optimize digestive function:

- Digestive Enzyme Complexes: Formulations containing amylase, lipase, and protease assist in breaking down complex macronutrients, easing the burden on the digestive system.

- Glutathione: As a key intracellular antioxidant, glutathione supports liver detoxification and cellular repair processes.

- Fiber Supplements: Soluble and insoluble fibers promote regular bowel movements and support a healthy microbiome, reducing the risk of constipation and diverticulitis.

By integrating these nutritional elements into daily life, individuals can enhance their abdominal health and create a robust foundation for overall wellness.

Optimizing Abdominal Wellness

Maintaining abdominal health extends beyond medical interventions and nutrition; it encompasses a holistic approach to lifestyle and wellness practices. Adopting these best practices can significantly contribute to a resilient and well-functioning digestive system.

Dietary and Hydration Strategies

- Balanced Diet: Consume a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats to support digestive health. Incorporate fiber-rich foods to aid in regular bowel movements and maintain optimal gut flora.

- Regular Hydration: Drinking adequate water throughout the day is essential for digestive efficiency, nutrient absorption, and preventing constipation. Aim for at least eight glasses daily, adjusting for activity levels and climate.

Physical Activity and Core Strength

- Regular Exercise: Engage in moderate physical activity such as walking, swimming, or cycling. Regular exercise stimulates intestinal motility and contributes to overall abdominal muscle tone.

- Core Strengthening: Incorporate exercises like planks, yoga, or Pilates to enhance core stability. A strong core supports the spine, alleviates back pain, and improves overall digestive function.

Stress Management and Mental Well-being

- Mindfulness Practices: Techniques such as meditation, deep breathing, or tai chi can help reduce stress levels. Chronic stress is known to exacerbate conditions like IBS and other digestive disorders.

- Adequate Sleep: Ensure a consistent sleep schedule, as restorative sleep is critical for cellular repair and hormonal balance that affects appetite and digestion.

Regular Medical Check-ups

- Preventative Screenings: Routine visits to a healthcare provider can help detect early signs of abdominal issues. Screening tests, including colonoscopies and blood panels, are vital for preventive care.

- Monitoring Health Metrics: Keep track of weight, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels to manage metabolic risk factors that can influence abdominal health.

These practices, when integrated into daily routines, serve as proactive measures to sustain abdominal function, prevent disease, and promote long-term well-being.

Credible Health Resources

Access to reliable information and support is essential for managing abdominal health. Below is a curated list of reputable resources that can offer further insights and guidance.

Recommended Books

- “The Complete Anti-Inflammatory Diet for Beginners” by Dorothy Calimeris: A comprehensive guide offering practical dietary advice and recipes to reduce inflammation.

- “The Good Gut: Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health” by Justin Sonnenburg and Erica Sonnenburg: Explores the science behind gut health and provides actionable tips for improving digestive function.

Academic and Scientific Journals

- Journal of Gastroenterology: Features the latest research on digestive system diseases and innovative treatment approaches.

- Gut: A leading journal focusing on gastrointestinal health, offering peer-reviewed studies and clinical trial results.

Mobile Applications

- MyFitnessPal: An app designed to track nutrition and exercise, aiding in the management of digestive and metabolic health.

- Cara Care: Provides personalized insights and management tips for individuals dealing with gastrointestinal disorders.

Utilizing these resources can empower readers to stay informed and engaged in their health journeys, promoting proactive management of abdominal conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the main functions of the abdomen?

The abdomen is central to digestion, metabolism, and immunity. It houses organs that break down food, absorb nutrients, detoxify harmful substances, and provide structural support. Additionally, it contributes to hormonal regulation and temperature control through blood flow.

How can digestive disorders be prevented?

Prevention involves maintaining a balanced diet, staying hydrated, engaging in regular exercise, and managing stress. Routine medical check-ups and early screenings also play a critical role in identifying potential issues before they escalate into severe conditions.

What diagnostic tests are most effective for abdominal issues?

Imaging modalities like ultrasound, CT, and MRI, along with lab tests, endoscopy, and genetic screenings, are highly effective. These tests help pinpoint the underlying causes of abdominal symptoms and guide targeted treatment plans.

What lifestyle changes support abdominal health?

Adopting a fiber-rich diet, regular physical activity, stress management techniques, and adequate hydration can significantly boost abdominal wellness. Avoiding excessive alcohol and smoking also reduces the risk of digestive disorders.

Are natural supplements beneficial for abdominal conditions?

Yes, supplements such as omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, and herbal remedies like turmeric and ginger have shown benefits in reducing inflammation and supporting digestive health. However, it’s important to consult with a healthcare provider before starting any supplementation.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider regarding any medical concerns or treatment decisions.

We encourage you to share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your favorite social platform to help spread awareness and support abdominal health for everyone!