What is scleromalacia perforans?

Scleromalacia perforans is a rare but severe ocular condition that causes progressive thinning and degeneration of the sclera, the eye’s white outer coating. This condition is most commonly linked to long-term, poorly controlled systemic autoimmune diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Unlike other types of scleritis, scleromalacia perforans frequently presents with little or no pain and minimal inflammation, making it a particularly insidious and dangerous condition that can result in serious complications such as scleral perforation and potential loss of vision.

Anatomy and Function of the Sclera

The sclera is the tough, protective outer layer of the eye, made up primarily of collagen and elastic fibers. This fibrous tissue not only shapes and structurally supports the eye, but also serves as a point of attachment for the extraocular muscles that control eye movement. The sclera is usually opaque and white, adding to the eye’s appearance while protecting the more delicate internal structures from injury and infection. Its thickness varies throughout the eye, with thicker near the optic nerve and gradually thinning towards the front.

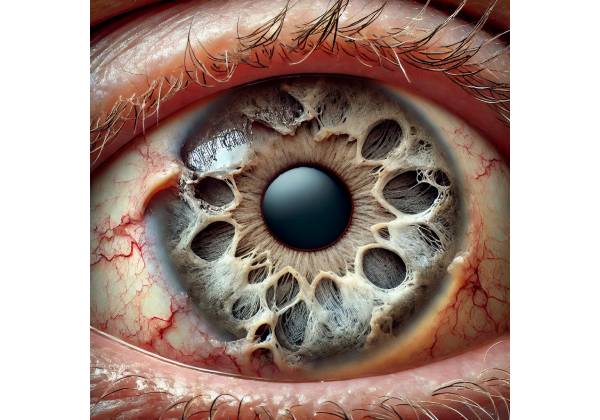

Scleromalacia perforans disrupts the sclera’s normal architecture, resulting in progressive thinning and necrosis, where the tissue becomes so thin that it appears transparent or even perforates. Chronic inflammation associated with systemic autoimmune conditions causes this degeneration, in which the body’s immune system mistakenly targets scleral tissue as if it were a foreign pathogen.

Pathology of Scleromalacia Perforans

Scleromalacia perforans is closely associated with autoimmune processes, particularly those seen in rheumatoid arthritis. In RA and other similar autoimmune diseases, the immune system attacks its own tissues, such as the joints, skin, and, in this case, sclera. The immune response in RA involves the activation of various inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and macrophages, which produce a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes. These substances, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), are especially damaging to the collagen and other structural components of the sclera.

Chronic inflammation causes scleral tissue to break down over time, resulting in patchy thinning and atrophy. Unlike other types of scleritis, scleromalacia perforans does not exhibit obvious inflammatory signs such as redness, swelling, or pain. This lack of typical inflammatory symptoms is thought to be due to the nature of these patients’ immune responses, in which destructive processes are ongoing but relatively silent. This makes the condition especially dangerous, as it can progress rapidly before being identified and treated.

As the sclera thins, the eye becomes more vulnerable to external injury, and in severe cases, spontaneous sclera perforation can occur, potentially resulting in vision loss or the need for enucleation (eye removal). Perforation is especially common in areas where the sclera has thinned or necrotic tissue has formed. Furthermore, the condition can cause secondary complications such as corneal involvement or uveitis, which can impair vision.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Scleromalacia perforans is a rare condition that primarily affects people with long-term, poorly controlled rheumatoid arthritis. The condition is more common in older adults, especially those who have had RA for a long time and may have other disease-related complications. Scleromalacia perforans is more common in women than in men, despite the fact that the condition can affect both sexes.

Other systemic autoimmune diseases linked to scleromalacia perforans include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis), and polyarteritis nodosa. However, rheumatoid arthritis is still the most common underlying condition associated with scleromalacia perforans.

The risk factors for developing scleromalacia perforans are:

- Long-term Rheumatoid Arthritis: The longer a person has RA, especially if it is not well-controlled with medications, the greater the risk of developing scleromalacia perforans.

- Severe Systemic Disease: People with severe RA or other autoimmune diseases, especially those with systemic involvement (e.g., vasculitis), are more vulnerable.

- Inadequate Immunosuppression: Patients who do not receive adequate immunosuppressive therapy or do not respond well to these therapies are more likely to develop scleromalacia perforans.

- Older Age: This condition affects more older adults, particularly those over the age of 60, which is most likely due to the cumulative effects of chronic autoimmune disease and decreased tissue repair capacity with age.

Clinical Presentation

Scleromalacia perforans presents with a distinct set of clinical characteristics that can make diagnosis difficult. Unlike other types of scleritis, which typically cause severe pain and visible inflammation, scleromalacia perforans may present with few or no symptoms in its early stages. This painless progression may result in a delay in diagnosis and treatment, increasing the risk of serious complications.

The main clinical features of scleromalacia perforans are:

- Asymptomatic or Mild Discomfort: Many patients with scleromalacia perforans do not experience severe pain like those with scleritis. Instead, they may experience mild discomfort or no symptoms at all, which is why the condition is frequently discovered by chance during routine eye examinations or when complications occur.

- Thinning of the Sclera: The most significant sign of scleromalacia perforans is progressive sclera thinning, which can be seen as areas of bluish or grayish discoloration where the underlying uvea is visible through the thinned sclera. In advanced cases, the sclera may become so thin that it appears transparent, and perforation may occur.

- Lack of Inflammation: Unlike other types of scleritis, scleromalacia perforans rarely exhibits significant redness, swelling, or other signs of inflammation. The absence of visible inflammation is a defining feature of the condition, distinguishing it from other forms of scleral disease.

- Corneal Involvement: In some cases, scleromalacia perforans can cause secondary corneal thinning or ulceration, particularly at the limbus (the junction of the cornea and the sclera). This can worsen vision and raise the risk of corneal perforation.

- Decreased Visual Acuity: As the disease progresses, patients may notice a gradual loss of visual acuity, especially if the cornea becomes involved or there is significant scleral thinning in areas affecting the visual axis. Perforation can cause sudden and severe vision loss.

Complications

Scleromalacia perforans can cause a variety of serious complications if not detected and treated promptly. This includes:

- Scleral Perforation: One of the most serious complications of scleromalacia perforans is spontaneous scleral perforation, which can result in the extrusion of intraocular contents and the loss of an eye. This complication is especially common in areas where the sclera has thinned or there is necrosis.

- Infection: The thinning and necrosis of the sclera in scleromalacia perforans provide a potential entry point for infections, which can lead to endophthalmitis—a severe and potentially blinding infection inside the eye.

- Secondary Glaucoma: Chronic inflammation associated with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis can cause secondary glaucoma in some cases, especially if the inflammation affects the trabecular meshwork or other parts of the anterior chamber.

- Corneal Perforation: If the condition progresses to secondary corneal involvement, there is a risk of corneal perforation, which can cause significant vision loss and necessitate urgent surgical intervention.

Prognosis

The prognosis for scleromalacia perforans is largely determined by the degree of scleral involvement, the rate of progression, and the efficacy of treatment. Early diagnosis and treatment of the underlying autoimmune condition are critical for avoiding serious complications and preserving vision. In cases where the disease is advanced or perforation has occurred, the prognosis is poor, with a high risk of vision loss or the need for surgical intervention to save the eye.

Diagnostic Techniques for Scleromalacia Perforans

To diagnose scleromalacia perforans, a comprehensive approach is required, combining a detailed clinical examination with advanced imaging techniques to assess the extent of scleral thinning and detect any complications. Because scleromalacia perforans frequently presents with minimal symptoms, particularly in its early stages, a high level of suspicion is required, especially in patients with a history of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. The following are the primary diagnostic methods for identifying and assessing scleromalacia perforans.

Clinical Examination

- Biomicroscopy with a Slit Lamp

- The slit-lamp examination is a critical diagnostic tool in ophthalmology, allowing for a thorough examination of the anterior segment of the eye, including the sclera. During this examination, the ophthalmologist can see areas of scleral thinning that may appear bluish or grayish as the underlying uvea becomes visible. In advanced cases, the sclera may be nearly transparent, revealing the choroid beneath.

- Despite visible scleral thinning, scleromalacia perforans differs from other types of scleritis in that there is no significant inflammation or pain present. The slit-lamp examination may also reveal areas of necrosis where the scleral tissue has degraded, increasing the risk of perforation.

- Ophthalmoscopy:

- Ophthalmoscopy, specifically indirect ophthalmoscopy, is used to assess the posterior segment of the eye. Although scleromalacia perforans primarily affects the anterior sclera, ophthalmoscopy can reveal any secondary effects on the retina, choroid, or optic nerve. This is especially important if the patient reports vision changes, which may indicate complications like posterior scleritis or retinal involvement.

- Visual Acuity Test:

- Visual acuity testing is a standard part of the clinical examination and is critical in determining the effect of scleromalacia perforans on the patient’s vision. A decrease in visual acuity may indicate corneal involvement, the onset of secondary glaucoma, or other complications requiring immediate attention.

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasound Biomicroscopy(UBM):

- Ultrasound biomicroscopy is an advanced imaging technique that produces high-resolution images of the anterior segment, including the sclera. UBM is especially useful in cases of scleromalacia perforans because it allows for precise measurement of scleral thickness and thinning. This imaging modality can detect areas of thinning that are not visible on clinical examination, allowing for early detection of potential perforation sites.

- B-Scan Ultrasoundography:

- B-scan ultrasonography is another useful tool, particularly for assessing the posterior segment in cases where scleromalacia perforans is associated with posterior scleritis or other complications. B-scan can detect scleral thickening, choroidal detachment, and fluid collections that would not be visible under direct examination.

- Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT):

- OCT is a non-invasive technique for obtaining cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid. While OCT is more commonly used to evaluate retinal conditions, it can also be useful in detecting secondary complications of scleromalacia perforans, such as macular edema, choroidal folds, or retinal layer involvement.

- Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT):

- AS-OCT is a subset of OCT that focuses on imaging the anterior segment of the eye. It can produce detailed images of the cornea, anterior chamber, and sclera. AS-OCT can be especially useful in determining the extent of scleral thinning and monitoring changes over time, particularly in patients being followed for disease progression.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging(MRI):

- MRI is occasionally used to evaluate scleromalacia perforans, especially when orbital involvement is suspected or to determine the extent of scleral thinning in relation to the surrounding tissues. MRI can provide detailed images of the orbit and help plan surgical interventions if necessary.

Lab Tests

While imaging and clinical examination are critical to the diagnosis of scleromalacia perforans, laboratory tests play an important role in identifying and managing the underlying systemic autoimmune condition.

- Antibodies to Rheumatoid Factor (RF) and Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide (Anti-CCP)

- These are diagnostic tests for rheumatoid arthritis, the most common systemic condition linked to scleromalacia perforans. Elevated levels of RF and anti-CCP antibodies strongly indicate the presence of RA, which can help guide the overall treatment plan.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-reactive Protein (CRP):

- ESR and CRP are indicators of systemic inflammation. Elevated levels of these markers may indicate active systemic inflammation and can help monitor treatment efficacy.

- Complete Blood Count(CBC):

- A complete blood count (CBC) can provide valuable information about the patient’s overall health and may reveal signs of infection, anemia, or other systemic conditions that could affect scleromalacia perforans treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating scleromalacia perforans from other ocular conditions is critical for effective treatment. Conditions to consider are:

- Necrotising Scleritis with Inflammation

- Unlike scleromalacia perforans, necrotizing scleritis is usually painful and accompanied by severe inflammation. However, because both conditions can cause scleral thinning and perforation, distinguishing between them requires careful examination and imaging.

- Non-necrotizing Scleritis:

- Non-necrotizing scleritis, including diffuse and nodular forms, causes inflammation and pain, which are not typical of scleromalacia perforans.

- Episcleritis:

- Episcleritis is a superficial inflammation of the episclera that is usually less severe and does not cause scleral thinning. It is typically self-limiting and not associated with systemic disease, distinguishing it from scleromalacia perforans.

Treatment Approaches for Scleromalacia Perforans

Scleromalacia perforans management is complex and necessitates a multidisciplinary approach that addresses both the disease’s ocular manifestations and the underlying systemic autoimmune condition, which is most commonly rheumatoid arthritis. Early and aggressive treatment is required to prevent disease progression and avoid serious complications such as scleral perforation and vision loss.

Medical Management

- Immunosuppressive Treatment:

- Systemic Corticosteroids: The first line of treatment for scleromalacia perforans is usually systemic corticosteroids, such as prednisone, which reduce inflammation and prevent further scleral thinning. Corticosteroids are frequently started at high doses and then tapered gradually based on the patient’s response. Long-term corticosteroid use, however, has significant side effects, so they are frequently combined with other immunosuppressive agents.

- Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): DMARDs, such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil, are frequently used to treat the underlying autoimmune disease and slow the progression of scleromalacia perforans. These drugs modulate the immune response, reducing the need for long-term corticosteroid use.

- Biologic Agents: When conventional DMARDs are insufficient or contraindicated, biologic agents such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab) or B-cell depleting agents (e.g., rituximab) can be used. These drugs target specific immune system pathways, providing a more targeted approach to reducing inflammation in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmune diseases.

- Topical Therapy:

- Topical Corticosteroids: While systemic therapy is the primary treatment, topical corticosteroids may be used in addition to manage local inflammation in the eye. However, because of the deeper nature of scleral involvement, their effectiveness in cases of scleromalacia perforans is limited.

- Lubricating Eye Drops: Patients with scleromalacia perforans may benefit from artificial tears or lubricating eye drops to alleviate dryness and irritation, but these treatments do not treat the underlying condition.

Surgical Management

In cases where medical management fails to control the disease or prevent complications, surgical intervention may be required. The goal of surgery is usually to strengthen the weakened scleral tissue and prevent perforation.

- Scleral Grafting:

- Scleral grafting is a surgical procedure that involves transplanting healthy donor scleral tissue into areas of the eye where the sclera has thinned significantly. This graft provides structural support to the eye, lowering the risk of perforation and contributing to the eye’s integrity. Scleral grafting is especially important in advanced cases where the risk of perforation is high or necrotic tissue must be removed.

- Conjunctiva Flap Surgery:

- In some cases, a conjunctival flap (a piece of tissue from the conjunctiva, the thin membrane that covers the sclera) can be used to conceal scleral thinning. This procedure protects the underlying sclera and promotes healing. Conjunctival flap surgery is frequently performed in conjunction with other surgical procedures, such as scleral grafting.

- Enucleation:

- In severe cases where the eye is no longer viable due to extensive scleral perforation or intractable pain, enucleation (eye removal) may be required. This procedure is considered a last resort, but it may be necessary to avoid further complications, such as infection, or to relieve severe pain. Enucleation is usually followed by the placement of an ocular prosthesis.

Treatment of Underlying Systemic Disease

Given that scleromalacia perforans is frequently associated with systemic autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, treating the underlying condition is critical. This entails working closely with a rheumatologist to ensure optimal control of the autoimmune disease through the use of DMARDs, biologic agents, and other treatments as needed. Regular disease activity monitoring and treatment regimen adjustments are required to prevent the recurrence or worsening of scleromalacia perforans.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Patients with scleromalacia perforans should see their ophthalmologist and rheumatologist on a regular basis to monitor the disease’s progression and treatment efficacy. Regular ophthalmic examinations are required to assess the sclera’s integrity and detect early signs of complications such as perforation or corneal involvement. Imaging studies, such as ultrasound or OCT, can be used on a regular basis to monitor scleral thickness changes and guide treatment decisions.

Patients should be educated on the warning signs of complications, such as sudden changes in vision, increased eye pain, or new areas of scleral thinning, and advised to seek immediate medical attention if they occur. Early intervention is critical in preventing irreversible damage and preserving vision.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Ocular Inflammatory Disease and Uveitis Manual” by Andrew Dick and Peter G. Watson: This book provides in-depth information on various inflammatory eye conditions, including scleromalacia perforans, offering valuable insights into diagnosis and management.

- “Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach” by Jack J. Kanski and Brad Bowling: A comprehensive resource on ophthalmic conditions, this textbook covers the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of scleromalacia perforans.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO provides extensive resources on ocular conditions, including scleromalacia perforans, and offers guidelines for both patients and healthcare professionals.

- Arthritis Foundation: This organization offers support and information for individuals with rheumatoid arthritis, including resources on managing associated conditions like scleromalacia perforans.

- National Eye Institute (NEI): Part of the NIH, the NEI provides reliable information on eye diseases, research, and support resources for patients with conditions like scleromalacia perforans.