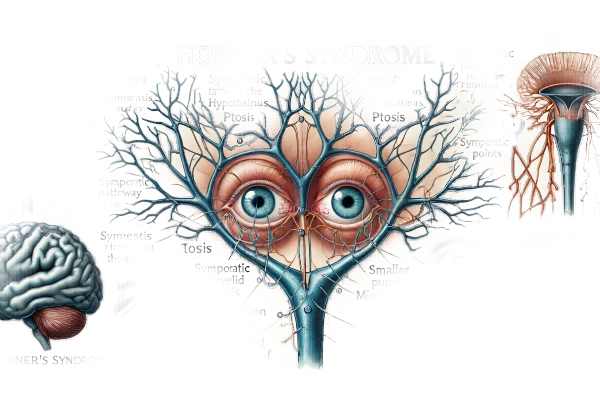

What is Horner Syndrome?

Horner’s syndrome, also known as oculosympathetic paresis, is a neurological disorder caused by a disruption of the sympathetic nerves that supply the eye and surrounding facial muscles. This condition presents with the classic triad of symptoms: ptosis (drooping of the upper eyelid), miosis (constricted pupil), and anhidrosis (absence of sweating) on the affected side of the face. Horner’s syndrome can be congenital or acquired, and it is frequently indicative of an underlying pathology, necessitating extensive investigation to determine the root cause.

Deep Dive into Horner’s Syndrome

Horner’s syndrome is a rare condition caused by the interruption of sympathetic pathways that innervate the eye and facial muscles. Horner’s syndrome is caused by a sympathetic pathway that runs from the hypothalamus to the eye and contains three neurons. Any disruption in this pathway can cause the syndrome’s characteristic symptoms.

Anatomy and Pathophysiology

The sympathetic innervation of the eye includes three neurons:

- First-Order Neurons: These neurons originate in the hypothalamus and travel through the brainstem to the spinal cord, eventually terminating in the intermediolateral cell column at the C8-T2 levels (Budge’s ciliospinal center).

- Second-Order Neurons: These neurons leave the spinal cord, cross the apex of the lung, and ascend the sympathetic chain to synapse in the superior cervical ganglion.

- Third-Order Neurons: The final neurons in this pathway travel from the superior cervical ganglion down the internal carotid artery, through the cavernous sinus, and into the orbit, where they innervate the pupil dilator muscle, the superior tarsal muscle (Müller’s muscle) of the eyelid, and the sweat glands of the forehead and face.

Horner’s syndrome can be caused by a disruption at any point in this pathway. The location of the lesion determines whether the syndrome is considered first-order (central), second-order (preganglionic), or third-order (postganglionic).

Etiology

Horner’s syndrome can result from a variety of causes, including:

- Congenital Causes: Present at birth, frequently without a known cause, but may be linked to birth trauma.

- Trauma: A physical injury to the head, neck, or chest can harm the sympathetic pathway.

- Neoplasms: Tumors such as neuroblastomas, lung cancers (particularly Pancoast tumors), and thyroid carcinomas can compress or penetrate the sympathetic chain.

- Vascular Causes: Carotid artery dissection, stroke, and aneurysms can all damage sympathetic nerves.

- Infectious and Inflammatory Conditions: Herpes zoster, sarcoidosis, and autoimmune diseases can all have an effect on the sympathetic nervous system.

- Iatrogenic Causes: Surgical procedures or medical interventions that unintentionally harm the sympathetic nerves.

Clinical Manifestations

Horner’s syndrome is characterized by several distinct ocular and facial symptoms:

- Ptosis: Mild upper-eyelid drooping caused by superior tarsal muscle paralysis. This ptosis is typically less severe than that caused by third cranial nerve palsy.

- Miosis: pupil constriction caused by unopposed parasympathetic innervation. The affected pupil is smaller and exhibits delayed or absent dilation in low light (anisocoria).

- Anhidrosis: Reduced or absent sweating on the affected side of the face, depending on the severity of the lesion. Anhidrosis is usually more widespread with central or preganglionic lesions.

- Enophthalmos: The appearance of a sunken eye caused by ptosis and narrowing of the palpebral fissure, not true posterior displacement of the eye.

- Heterochromia: Congenital Horner’s syndrome may result in a lighter iris color due to interrupted sympathetic stimulation during development.

Effect on Vision and Quality of Life

While Horner’s syndrome does not directly impair vision, the symptoms can have an impact on visual function and quality of life. Ptosis can block the visual field, especially in severe cases. Anisocoria can cause cosmetic issues and may be linked to photophobia (light sensitivity) due to the smaller pupil’s inability to dilate properly in low light conditions. Furthermore, the underlying causes of Horner’s syndrome, such as tumors or vascular anomalies, can have serious health consequences that necessitate early diagnosis and treatment.

Associated Conditions

Horner’s syndrome may coexist with other neurological symptoms, depending on the location of the lesion. For example:

- Lateral Medullary Syndrome (Wallenberg Syndrome): This condition is caused by a stroke in the lateral medulla and can include Horner’s syndrome as well as symptoms like vertigo, ataxia, and sensory deficits.

- Pancoast Syndrome: Horner’s syndrome, shoulder pain, and hand muscle atrophy are symptoms associated with apical lung tumors caused by brachial plexus involvement.

Prognosis

The prognosis of Horner’s syndrome is largely determined by the underlying cause. In cases of benign conditions or minor trauma, symptoms may improve over time or remain stable without significant progression. However, when associated with malignancies or significant vascular lesions, the prognosis can be more uncertain, necessitating comprehensive treatment of the underlying condition.

Methods for Detecting Horner’s Syndrome

Horner’s syndrome is diagnosed using a combination of clinical examination, pharmacological testing, and imaging studies to confirm its presence and determine the underlying cause.

Clinical Examination

Diagnosing Horner’s syndrome requires a thorough clinical examination.

- History Taking: Obtain a detailed patient history to identify any recent trauma, surgical procedures, or symptoms that may indicate an underlying condition.

- Physical Examination: Check for ptosis, anisocoria, and anhidrosis. The degree of ptosis and miosis can be measured, and enophthalmos can be identified.

Pharmaceutical Testing

Pharmacological tests can help confirm the diagnosis of Horner’s syndrome and localise the lesion:

- The Cocaine Test: Cocaine drops (4-10%) are administered to both eyes. In a normal eye, cocaine inhibits norepinephrine reuptake, causing pupil dilation. Horner’s syndrome occurs when the pupil fails to dilate due to a lack of norepinephrine.

- Apraclonidine Test: Apraclonidine drops (0.5-1%) can reverse anisocoria in Horner’s syndrome. The affected pupil dilates due to the hypersensitivity of the denervated adrenergic receptors, whereas the normal pupil remains constant or slightly constricts.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are critical for determining the underlying cause of Horner’s syndrome.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI of the brain, neck, and chest can detect lesions affecting the sympathetic pathway, such as tumors, strokes, or vascular anomalies.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: CT scans can detect bone abnormalities, lung tumors, and other structural lesions in the head, neck, and chest.

- Carotid Ultrasound: This imaging modality can detect carotid artery dissection, which is a possible cause of Horner’s syndrome, especially in cases of neck trauma or vascular risk factors.

Treatment.

Horner’s syndrome is treated primarily by addressing the underlying cause, as the syndrome is a symptom rather than a disease. Management strategies vary by etiology, ranging from medical therapy to surgical interventions.

Standard Treatment Options:

- Medical Management: If Horner’s syndrome is caused by an underlying medical condition, such as a vascular anomaly (e.g., carotid artery dissection) or an infectious process (e.g., herpes zoster), treating the underlying condition can help to alleviate Horner’s symptoms. For example:

- Antibiotics or antivirals: Used to treat infections affecting the sympathetic nervous system, such as herpes zoster.

- Anticoagulants or Antiplatelet Therapy: For vascular causes such as carotid artery dissection, to avoid further thromboembolic events.

- Steroids or immunosuppressive agents: Used to treat inflammatory or autoimmune conditions that disrupt sympathetic innervation.

- Surgical Interventions: When Horner’s syndrome is caused by compressive lesions like tumors, the tumor may need to be surgically removed or debulked. Procedures may include:

- Neurosurgery: The removal of tumors in the brain or spinal cord that affect the sympathetic pathway.

- Thoracic Surgery: For the removal of Pancoast tumors in the lung apex.

- Vascular Surgery: To repair aneurysms or dissections that affect the sympathetic nerves.

- Symptomatic Treatment: If the underlying cause is untreatable or the symptoms persist despite treatment, symptomatic management is required.

- Ptosis: Eyelid surgery or ptosis crutches (a device attached to glasses that lifts the drooping eyelid) can help improve visual function and appearance.

- Miosis: Topical apraclonidine drops can temporarily dilate the miotic pupil in cases of anisocoria that cause significant cosmetic or functional impairment.

Innovative and Emerging Therapies

- Gene Therapy: Research into gene therapy aims to repair or replace defective genes involved in conditions that cause Horner’s syndrome, potentially providing a long-term cure.

- Neurostimulation: Techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and deep brain stimulation (DBS) are being investigated to improve neural function and potentially alleviate symptoms associated with nerve damage.

- Advanced Imaging and Minimally Invasive Techniques: Advances in imaging technologies and minimally invasive surgical techniques enable more precise identification and treatment of the underlying causes of Horner’s syndrome, with shorter recovery times and fewer complications.

- Pharmacological Innovations: The development of new drugs that target specific pathways involved in the etiology of Horner’s syndrome may lead to more effective treatment options in the future.

Horner’s syndrome treatment strategies aim to improve affected individuals’ quality of life and visual function by addressing both the underlying cause and symptomatic relief. Emerging therapies continue to hold promise for more effective and minimally invasive treatments.

Best Practices to Avoid Horner’s Syndrome:

- Schedule regular medical check-ups. Regular health check-ups can aid in the early detection and treatment of conditions that may lead to Horner’s syndrome, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and other vascular diseases.

- Maintain a Healthy Lifestyle: A well-balanced diet, regular exercise, and quitting smoking can all help prevent cardiovascular disease, which is a major risk factor for Horner’s syndrome.

- Protective Gear: Wear appropriate protective gear when participating in high-risk activities such as contact sports or construction work to reduce the risk of traumatic injuries that could harm the sympathetic pathway.

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Proper management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension can lower the risk of complications leading to Horner’s syndrome.

- Infection Control: By practicing good hygiene, getting vaccinations, and treating illnesses on time, you can lower your chances of developing sympathetic nerve complications.

- Stress Management: Chronic stress can exacerbate a variety of pre-existing conditions. Mindfulness, yoga, and getting enough sleep can all help to reduce stress.

- Prompt Medical Attention: Seek immediate medical care if you experience sudden severe headaches, neck pain, or vision changes, as these could be symptoms of a serious condition such as carotid artery dissection or stroke.

- Awareness and Education: Educating yourself and others about Horner’s syndrome symptoms and risk factors can lead to early detection and treatment, reducing the likelihood of serious complications.

Individuals who follow these preventive measures can reduce their risk of developing Horner’s syndrome and its complications, resulting in improved overall health and well-being.

Trusted Resources

Books

- “Neuro-Ophthalmology: Diagnosis and Management” by Andrew G. Lee and Paul W. Brazis

- “Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology: A Practical Guide” by Ambar Chakravarty

- “Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology” by Neil R. Miller and Nancy J. Newman