Sarcoidosis is a complex, multisystem inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of tiny clumps of inflammatory cells called granulomas. These granulomas can form in virtually any organ of the body, but they most commonly affect the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, and eyes. While the exact cause of sarcoidosis remains unknown, it is thought to result from an exaggerated immune response to an unknown trigger, possibly an infection or environmental factor. Sarcoidosis can vary significantly in its presentation, severity, and progression, making it a challenging condition to diagnose and manage.

Pathophysiology of Sarcoidosis

The hallmark of sarcoidosis is the formation of non-caseating granulomas, which are small, localized areas of inflammation that do not undergo necrosis. Granulomas are formed when the immune system attempts to wall off substances it perceives as foreign but is unable to eliminate. In sarcoidosis, the granulomas consist of tightly packed clusters of immune cells, including macrophages, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells.

The exact mechanism by which these granulomas form in sarcoidosis is not fully understood. It is believed that in genetically predisposed individuals, exposure to certain environmental or infectious agents triggers an abnormal immune response. This response leads to the activation of T-helper cells and macrophages, which release cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. These substances promote the aggregation of immune cells and the formation of granulomas.

In the lungs, which are the most commonly affected organ in sarcoidosis, granulomas typically form in the interstitium, the tissue that surrounds and supports the alveoli (tiny air sacs). Over time, these granulomas can cause fibrosis (scarring) of the lung tissue, leading to reduced lung function and, in severe cases, pulmonary hypertension and respiratory failure.

The granulomas in sarcoidosis can also affect other organs, including the lymphatic system, skin, eyes, heart, liver, kidneys, and nervous system. The impact on these organs can vary from mild and asymptomatic to severe and life-threatening, depending on the number and location of the granulomas.

Clinical Presentation of Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is often referred to as the “great imitator” because its symptoms can mimic those of many other diseases. The condition can present acutely, with a sudden onset of symptoms, or chronically, with symptoms that develop gradually over time. The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis can vary widely depending on the organs involved and the extent of the disease.

- Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: The lungs are the most commonly affected organ in sarcoidosis, with more than 90% of patients experiencing some degree of lung involvement. Pulmonary symptoms may include a persistent dry cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, and wheezing. Some patients may be asymptomatic, with the disease only detected incidentally on a chest X-ray. Pulmonary sarcoidosis can progress to cause interstitial lung disease, characterized by scarring and stiffening of the lung tissue, which can lead to severe respiratory impairment.

- Lymphadenopathy: Enlarged lymph nodes, particularly in the chest (hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy), are a common finding in sarcoidosis. Lymphadenopathy may also occur in other areas, such as the neck, armpits, or groin. While enlarged lymph nodes in sarcoidosis are usually painless, they can sometimes cause discomfort or compress adjacent structures.

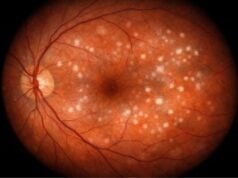

- Ocular Sarcoidosis: The eyes are frequently involved in sarcoidosis, with up to 50% of patients experiencing some form of ocular involvement. Ocular sarcoidosis can affect any part of the eye, leading to symptoms such as redness, pain, blurred vision, and sensitivity to light. Uveitis, an inflammation of the uveal tract (which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid), is the most common ocular manifestation of sarcoidosis. If left untreated, ocular sarcoidosis can lead to complications such as glaucoma, cataracts, and even blindness.

- Cutaneous Sarcoidosis: Skin involvement occurs in about 25% of sarcoidosis patients and can present in a variety of ways. Common skin manifestations include erythema nodosum (tender red or violet nodules, usually on the shins), lupus pernio (raised, purple skin lesions, often on the face), and maculopapular rashes. Skin lesions may be disfiguring and can persist even after other symptoms of sarcoidosis have resolved.

- Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis is less common but can be life-threatening. Cardiac sarcoidosis may present with symptoms such as palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, or syncope (fainting). It can cause arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), heart block, or heart failure. In some cases, cardiac sarcoidosis may be the first or only manifestation of the disease, making it particularly difficult to diagnose.

- Neurological Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis can affect the nervous system in about 5-10% of cases, leading to a condition known as neurosarcoidosis. Neurosarcoidosis can involve the brain, spinal cord, cranial nerves, and peripheral nerves. Symptoms may include headaches, seizures, facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy), numbness, weakness, or cognitive changes. Neurosarcoidosis is a serious complication and may require aggressive treatment to prevent permanent neurological damage.

- Hepatic and Splenic Sarcoidosis: The liver and spleen can also be affected by sarcoidosis, often without causing noticeable symptoms. However, some patients may experience hepatosplenomegaly (enlargement of the liver and spleen), jaundice, or abnormal liver function tests. In rare cases, sarcoidosis can lead to cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) and portal hypertension.

- Renal Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis can affect the kidneys, leading to hypercalcemia (elevated calcium levels in the blood) and nephrocalcinosis (calcium deposits in the kidneys). Chronic kidney disease and renal failure can occur in severe cases.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Sarcoidosis is a global disease that can affect individuals of any age, race, or gender. However, certain populations are more commonly affected. Sarcoidosis is most prevalent in adults aged 20 to 40 years, with a slight female predominance. The condition is more common in African Americans, who are also more likely to experience severe and chronic forms of the disease compared to Caucasians. Sarcoidosis is also more prevalent in individuals of Scandinavian, Irish, and Caribbean descent.

The exact cause of sarcoidosis remains unknown, but it is believed to result from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. Several genes have been implicated in increasing susceptibility to sarcoidosis, particularly those involved in the immune system’s regulation. Environmental exposures, such as infections (e.g., mycobacteria or viruses), occupational exposures (e.g., beryllium or organic dust), and environmental toxins, have been proposed as potential triggers for the disease, although definitive evidence is lacking.

Family history is another risk factor for sarcoidosis, with studies showing that individuals with a first-degree relative affected by sarcoidosis have a higher risk of developing the disease themselves. This familial clustering suggests a genetic predisposition, although the specific genetic factors involved are still being investigated.

Prognosis

The prognosis for sarcoidosis varies widely depending on the organs involved and the severity of the disease. In many cases, sarcoidosis resolves spontaneously without treatment, particularly in patients with acute or mild disease. However, some patients may experience chronic or progressive disease, leading to significant organ damage and disability.

Pulmonary sarcoidosis, the most common form of the disease, has a generally favorable prognosis, with many patients achieving remission within a few years. However, a subset of patients may develop chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis, leading to fibrosis, respiratory failure, and, in rare cases, death. Cardiac, neurological, and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis are associated with a worse prognosis and may require long-term treatment to manage symptoms and prevent complications.

Regular monitoring and follow-up with a healthcare provider are essential for managing sarcoidosis, as the disease can be unpredictable and may recur after periods of remission.

Diagnostic Methods

Diagnosing sarcoidosis can be challenging due to the variability in its presentation and the absence of a definitive diagnostic test. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis is typically made based on a combination of clinical findings, imaging studies, laboratory tests, and, most importantly, tissue biopsy showing non-caseating granulomas.

Clinical Evaluation

The diagnostic process begins with a thorough clinical evaluation, including a detailed patient history and physical examination. The clinician will assess the patient’s symptoms, medical history, and any potential exposures that may be relevant to sarcoidosis. Because sarcoidosis can affect multiple organs, a comprehensive evaluation is necessary to identify all possible sites of involvement.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies play a crucial role in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, particularly in assessing lung involvement, which is the most common manifestation of the disease.

- Chest X-ray: A chest X-ray is often the first imaging study performed in patients suspected of having sarcoidosis. It can reveal characteristic findings such as bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (enlarged lymph nodes in the chest) and pulmonary infiltrates (areas of inflammation in the lungs). The extent of lung involvement can be staged using a standardized system based on chest X-ray findings.

- High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT): HRCT is more sensitive than a chest X-ray and provides detailed images of the lungs and other thoracic structures. HRCT can detect subtle abnormalities that may not be visible on a chest X-ray, such as ground-glass opacities, nodules, and fibrosis.

HRCT is particularly useful in evaluating the extent of pulmonary involvement in sarcoidosis, as well as identifying other thoracic manifestations such as pleural thickening or peribronchial nodules. It also helps in distinguishing sarcoidosis from other interstitial lung diseases that may present with similar radiographic findings.

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory tests are used to assess organ function, identify markers of inflammation, and rule out other conditions that can mimic sarcoidosis. While no single blood test can definitively diagnose sarcoidosis, certain tests can provide supportive evidence.

- Serum Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE): Elevated levels of ACE are often found in patients with sarcoidosis and reflect granuloma formation. However, ACE levels are not specific to sarcoidosis and can be elevated in other conditions. Therefore, ACE levels are used in conjunction with other diagnostic findings rather than as a standalone test.

- Calcium Levels: Hypercalcemia (elevated blood calcium levels) and hypercalciuria (elevated urinary calcium excretion) are common in sarcoidosis due to increased production of active vitamin D by granulomas. Monitoring calcium levels is important, as hypercalcemia can lead to kidney stones and other complications.

- Liver Function Tests: Sarcoidosis can affect the liver, leading to elevated liver enzymes. Abnormal liver function tests may prompt further evaluation of hepatic involvement, such as imaging or biopsy.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Inflammatory Markers: A CBC can help identify anemia or other blood cell abnormalities that may be associated with sarcoidosis. Inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), are often elevated in sarcoidosis but are nonspecific.

Tissue Biopsy

The definitive diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires histological confirmation through tissue biopsy. The biopsy must show the presence of non-caseating granulomas, which are the hallmark of sarcoidosis. Tissue samples can be obtained from various sites, depending on the organs involved and the accessibility of affected tissues.

- Lung Biopsy: In cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis, a lung biopsy is often performed. This can be done through bronchoscopy with transbronchial lung biopsy, where small samples of lung tissue are taken using a bronchoscope inserted into the airways. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy (EBUS) can also be used to sample mediastinal lymph nodes.

- Skin Biopsy: For patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, a skin biopsy of the affected lesion is often straightforward and can provide a definitive diagnosis. The skin sample is examined under a microscope for granulomas.

- Lymph Node Biopsy: Enlarged peripheral lymph nodes can be biopsied to obtain tissue for examination. This is often done using fine-needle aspiration or excisional biopsy.

- Other Biopsy Sites: Depending on the organs involved, other biopsy sites may include the liver, heart, salivary glands, or conjunctiva (in cases of ocular sarcoidosis). The choice of biopsy site depends on clinical findings and the likelihood of obtaining an adequate tissue sample.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

PFTs are commonly performed in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis to assess lung function and monitor disease progression. These tests measure lung volumes, airflow, and gas exchange, providing insight into the extent of lung involvement.

- Spirometry: Spirometry measures the amount of air a patient can inhale and exhale, as well as the speed of airflow. Reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) or forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) may indicate restrictive lung disease, which is common in sarcoidosis.

- Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO): DLCO assesses how well the lungs transfer gas from inhaled air to the bloodstream. A reduced DLCO may indicate impaired gas exchange due to granulomatous inflammation or fibrosis in the lungs.

Ophthalmologic Examination

Given the high prevalence of ocular involvement in sarcoidosis, a thorough eye examination by an ophthalmologist is recommended for all patients. The examination includes:

- Slit-Lamp Examination: This test uses a specialized microscope to examine the anterior structures of the eye, including the cornea, iris, and lens. It can detect signs of uveitis, which is common in ocular sarcoidosis.

- Fundoscopy: Fundoscopy allows the ophthalmologist to visualize the back of the eye, including the retina and optic nerve. This examination can reveal granulomas, retinal vasculitis, or optic nerve swelling.

Electrocardiogram (ECG) and Cardiac Imaging

For patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis, an ECG and cardiac imaging are essential diagnostic tools.

- ECG: An ECG can detect abnormalities in heart rhythm or conduction, such as atrioventricular block or arrhythmias, which may indicate cardiac involvement.

- Cardiac MRI: Cardiac MRI is a highly sensitive imaging modality that can detect granulomas, fibrosis, and inflammation in the heart. It is particularly useful for diagnosing cardiac sarcoidosis and assessing the extent of cardiac involvement.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): PET scanning with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is used to identify areas of active inflammation in the heart and other organs. It is valuable in the evaluation of cardiac sarcoidosis and in monitoring response to treatment.

Sarcoidosis Management

The management of sarcoidosis is highly individualized, depending on the organs involved, the severity of the disease, the presence of symptoms, and the overall health of the patient. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce inflammation, prevent organ damage, and manage symptoms. In many cases, sarcoidosis may resolve spontaneously without the need for treatment, particularly in patients with mild or asymptomatic disease. However, when intervention is required, several treatment options are available.

Observation and Monitoring

For patients with asymptomatic or mild sarcoidosis, particularly when it affects only the lungs or lymph nodes, a “watch and wait” approach may be appropriate. Regular monitoring includes follow-up visits with clinical evaluations, imaging studies (such as chest X-rays or CT scans), and pulmonary function tests to assess any progression of the disease. In some cases, sarcoidosis may spontaneously remit, making observation a viable strategy. Close monitoring allows for early detection of disease progression or the development of symptoms, at which point treatment can be initiated.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids, particularly prednisone, are the cornerstone of sarcoidosis treatment due to their potent anti-inflammatory effects. They are often the first-line therapy for symptomatic sarcoidosis or when vital organs such as the lungs, heart, eyes, or nervous system are involved. Corticosteroids work by suppressing the immune system’s activity, reducing inflammation, and helping to resolve granulomas.

- Oral Corticosteroids: Prednisone is commonly prescribed in oral form, with the dosage tailored to the severity of the disease. A higher dose may be used initially to control active inflammation, followed by a gradual tapering to the lowest effective dose. The duration of corticosteroid therapy can vary, but treatment typically lasts for several months, and in some cases, long-term therapy may be necessary.

- Topical or Inhaled Corticosteroids: For patients with localized sarcoidosis, such as skin lesions or uveitis, topical corticosteroids (creams or eye drops) may be used to reduce inflammation. Inhaled corticosteroids can be beneficial for those with mild pulmonary sarcoidosis to reduce airway inflammation with minimal systemic side effects.

While corticosteroids are effective in controlling sarcoidosis, long-term use is associated with significant side effects, including weight gain, hypertension, osteoporosis, diabetes, and an increased risk of infections. Therefore, the risks and benefits of corticosteroid therapy must be carefully weighed, and patients should be monitored for adverse effects.

Immunosuppressive and Cytotoxic Agents

For patients who cannot tolerate corticosteroids or whose disease does not respond adequately to steroids, immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents may be used as steroid-sparing alternatives or adjuncts to therapy. These medications help to suppress the immune system and reduce inflammation, allowing for lower doses of corticosteroids to be used.

- Methotrexate: Methotrexate is one of the most commonly used immunosuppressive agents in sarcoidosis management. It is particularly effective for chronic or severe cases, including those with pulmonary, ocular, or neurological involvement. Methotrexate is typically administered weekly, either orally or via injection. Regular monitoring of liver function and blood counts is necessary due to potential side effects, such as liver toxicity and bone marrow suppression.

- Azathioprine: Azathioprine is another immunosuppressive medication that can be used to manage sarcoidosis, particularly when methotrexate is not tolerated or effective. It works by inhibiting the proliferation of immune cells and is often used in combination with low-dose corticosteroids.

- Leflunomide: Leflunomide is an alternative immunosuppressive agent that can be used in patients who are intolerant of methotrexate or azathioprine. It is effective in reducing inflammation and controlling sarcoidosis symptoms, particularly in cases of pulmonary or cutaneous involvement.

- Mycophenolate Mofetil: Mycophenolate mofetil is another option for patients with refractory sarcoidosis or those who experience significant side effects from other immunosuppressive medications. It is commonly used in patients with pulmonary, ocular, or renal involvement.

- Cyclophosphamide: In severe or life-threatening cases of sarcoidosis, particularly those involving the heart or nervous system, cyclophosphamide, a potent cytotoxic agent, may be used. Due to its significant toxicity, including the risk of bone marrow suppression and bladder toxicity, cyclophosphamide is generally reserved for the most severe cases and is administered under close medical supervision.

Biologic Agents

Biologic agents, particularly tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) inhibitors, are increasingly used in the management of sarcoidosis, especially in patients with refractory disease who do not respond to conventional therapies.

- Infliximab: Infliximab, a monoclonal antibody that targets TNF-alpha, has shown efficacy in treating sarcoidosis, particularly in cases involving the lungs, skin, or nervous system. Infliximab is administered via intravenous infusion and is typically used in combination with other immunosuppressive medications.

- Adalimumab: Adalimumab is another TNF-alpha inhibitor used in the treatment of sarcoidosis, particularly in cases of ocular sarcoidosis. It is administered via subcutaneous injection and may be considered for patients who do not respond to infliximab or other therapies.

Organ-Specific Treatments

In addition to systemic therapies, organ-specific treatments may be necessary depending on the organs affected by sarcoidosis.

- Ocular Sarcoidosis: Patients with ocular involvement, such as uveitis, may require topical corticosteroids or immunosuppressive eye drops. In severe cases, systemic therapy with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents may be necessary to prevent vision loss.

- Cardiac Sarcoidosis: Cardiac sarcoidosis requires aggressive management due to the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias or heart failure. In addition to systemic immunosuppressive therapy, patients may require antiarrhythmic medications, pacemaker implantation, or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) to manage arrhythmias.

- Neurosarcoidosis: Neurosarcoidosis can be challenging to treat and often requires high-dose corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or cyclophosphamide. Early intervention is crucial to prevent permanent neurological damage.

Lifestyle Modifications and Supportive Care

Patients with sarcoidosis can benefit from lifestyle modifications and supportive care to manage symptoms and improve their quality of life. This may include smoking cessation, regular exercise, a healthy diet, and pulmonary rehabilitation for those with lung involvement. Additionally, patients should be monitored for potential complications of sarcoidosis and its treatments, such as osteoporosis, diabetes, or infections, and appropriate preventive measures should be taken.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Sarcoidosis: A Clinician’s Guide” by Om Sharma: This comprehensive book offers an in-depth exploration of sarcoidosis, covering its pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management across various organ systems. It is a valuable resource for both healthcare professionals and patients seeking to understand the complexities of the disease.

- “Sarcoidosis: Medical and Clinical Aspects” by Donald N Mitchell: This book provides detailed information on the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of sarcoidosis, making it an essential resource for those managing the condition.

Organizations

- Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research (FSR): The FSR is a leading organization dedicated to finding a cure for sarcoidosis and improving care for those affected by the disease. It offers educational resources, patient support groups, and funding for research into sarcoidosis.

- American Lung Association (ALA): The ALA provides resources and support for individuals with lung conditions, including sarcoidosis. It offers educational materials, advocacy, and support services for patients and their families.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI): Part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), NHLBI provides information on sarcoidosis, current research initiatives, and clinical trials aimed at improving the understanding and treatment of the disease.