Stickler Syndrome is a hereditary connective tissue disorder that affects several systems in the body, including the eyes, ears, skeleton, and craniofacial structures. Stickler Syndrome, named after pediatrician Dr. Gunnar B. Stickler, who described the condition in 1965, is also known as hereditary progressive arthro-ophthalmopathy because it affects both joints and the eyes. Ocular manifestations are among the most significant and visually impairing aspects of the syndrome, so early identification and understanding are critical for effective disease management.

Genetic Basis and Pathogenesis

Stickler Syndrome is a genetically heterogeneous condition, which means it can be caused by mutations in multiple genes. The most commonly affected genes are COL2A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2, which all encode proteins involved in the production of type II and type XI collagen. Collagen is an important structural protein in the extracellular matrix of connective tissues, giving strength and stability to a variety of bodily structures such as the vitreous body of the eye, cartilage, and intervertebral discs.

Mutations in these collagen-related genes cause abnormal or insufficient collagen production, giving Stickler Syndrome its distinguishing features. Defective collagen in the eye can cause vitreoretinal degeneration, high myopia (severe nearsightedness), and an increased risk of retinal detachment. These ocular manifestations are frequently present at birth or early childhood and can progress with age, resulting in significant visual impairment if left untreated.

Early Ocular Manifestations

Stickler Syndrome has a variety of ocular manifestations, but high myopia is one of the earliest and most consistent. Stickler Syndrome causes high myopia, which usually appears in infancy or early childhood and progresses quickly. It is not uncommon for affected people to need corrective lenses from a young age. Stickler Syndrome’s myopia is frequently associated with other eye structural abnormalities, such as a long axial length (the distance from the front to the back of the eye) and sclera thinning.

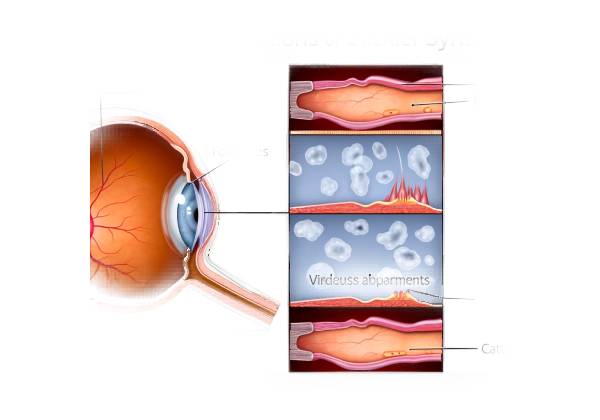

Another early ocular symptom is vitreous degeneration. The vitreous body is a clear, gel-like substance that sits between the lens and the retina. Stickler Syndrome is characterized by abnormal vitreous formation or degeneration over time. Stickler Syndrome is characterized by two types of vitreous abnormalities: Type 1, which has a “membranous” or “beaded” vitreous, and Type 2, which has a more normal appearance but less support. These vitreous changes can predispose the retina to detachment, a serious condition in which the retina separates from the surrounding tissue, resulting in vision loss.

Retinal Detachment

Stickler Syndrome’s most severe and vision-threatening ocular complication is retinal detachment. The retina is a light-sensitive layer in the back of the eye that transmits visual information to the brain. Detachment occurs when the retina separates from the layer of blood vessels that provides it with oxygen and nutrients, resulting in sudden and severe vision loss.

Stickler Syndrome patients face a significantly higher risk of retinal detachment than the general population. This increased risk stems from a combination of vitreous degeneration, which can cause traction on the retina, and structural abnormalities associated with high myopia. Retinal tears or holes may form in a thinned retina, allowing fluid to seep under it and cause detachment.

Symptoms of retinal detachment include the sudden appearance of floaters (small spots or lines that move through the field of vision), flashes of light, and a shadow or curtain over a portion of the visual field. Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that requires immediate surgical intervention to reattach the retina and avoid permanent vision loss.

Cataract and Glaucoma

Cataracts, or opacities in the lens of the eye, are another common ocular manifestation of Stickler syndrome. While cataracts are usually associated with aging, people with Stickler Syndrome frequently develop them at a much younger age, sometimes during childhood or adolescence. Cataracts in Stickler Syndrome can progress quickly, causing blurred vision, glare, and night vision issues.

Glaucoma, a group of eye conditions characterized by optic nerve damage, can occur in people with Stickler Syndrome, but it is less common than other ocular manifestations. Glaucoma in this context may be secondary to other eye problems, such as cataracts or retinal detachment, and if not treated properly, can lead to progressive vision loss. Elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) is the primary risk factor for glaucoma, and people with Stickler Syndrome should be closely monitored for signs of elevated IOP.

Impact on Vision

Stickler Syndrome can have a significant impact on vision, especially if not diagnosed and treated early. High myopia can cause a gradual decline in visual acuity, making it difficult for people to perform daily tasks without corrective lenses. Even with glasses or contact lenses, some people may continue to have poor visual clarity due to underlying structural abnormalities in the eye.

Retinal detachment is the most serious threat to vision in Stickler Syndrome. If not treated promptly, retinal detachment can cause permanent vision loss in the affected eye. Even after a successful surgical repair, some people may have residual visual deficits, such as decreased peripheral vision or difficulty with fine visual tasks.

Cataracts and glaucoma exacerbate the visual impairment associated with Stickler Syndrome. Cataracts can cause a gradual decline in vision that may not be completely reversible even after cataract surgery, especially if other ocular complications are present. Glaucoma, if left untreated, can cause irreversible optic nerve damage and progressive vision loss.

Variation in Ocular Manifestations

It is important to note that the ocular manifestations of Stickler Syndrome can differ greatly between affected individuals, even within the same family. This variation is due in part to the condition’s genetic heterogeneity, with different mutations resulting in distinct patterns of ocular involvement. Some people have mild myopia and are asymptomatic for the rest of their lives, whereas others develop multiple severe complications, such as retinal detachment and cataracts, at a young age.

In addition to the severity of ocular manifestations, there may be variation in the age of onset. While high myopia and vitreous degeneration are usually present at a young age, other complications, such as cataracts and glaucoma, may not appear until later in life. This variability emphasizes the importance of regular and comprehensive ophthalmologic examinations for people with Stickler Syndrome, as early detection and intervention can significantly improve outcomes.

Systemic Implications of Stickler Syndrome

While this article focuses on the ocular manifestations of Stickler Syndrome, it is important to recognize that the condition has significant systemic implications. Stickler Syndrome patients frequently have hearing loss, joint problems, and craniofacial abnormalities such as a cleft palate or the Pierre Robin sequence (a combination of a small lower jaw, tongue displacement, and airway obstruction). These systemic features can add to the disease’s overall burden and affect an individual’s quality of life.

Hearing loss, in particular, can exacerbate the difficulties experienced by people with Stickler Syndrome’s visual impairment. The combination of hearing and vision loss can make communication and navigation more difficult, especially in noisy or low-light settings. This dual sensory impairment can have a significant impact on educational and occupational opportunities, as well as social relationships.

Given the multisystem nature of Stickler Syndrome, a multidisciplinary approach to care is required. This strategy should include regular monitoring and management by ophthalmologists, audiologists, orthopedic specialists, and genetic counselors. Healthcare providers can help people with Stickler Syndrome live their best lives by addressing all aspects of the condition.

Diagnostic methods

Stickler Syndrome is diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and genetic testing, especially when ocular manifestations exist. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical for determining appropriate treatment and avoiding serious complications like retinal detachment.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing Stickler Syndrome is a thorough clinical examination by an ophthalmologist. This examination includes a thorough review of the patient’s ocular history, with a focus on symptoms like high myopia, floaters, and previous episodes of retinal detachment. The ophthalmologist will thoroughly examine the eye, including the anterior segment, vitreous, and retina, with a slit-lamp microscope.

The assessment of the vitreous body, which frequently reveals characteristic abnormalities in people with Stickler Syndrome, is an important part of the clinical examination. An ophthalmologist will look for signs of vitreous degeneration, such as a membranous or beaded appearance, to help distinguish Stickler Syndrome from other causes of myopia. Furthermore, the retina will be thoroughly examined for signs of thinning, tears, or detachment.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are critical in diagnosing Stickler Syndrome and determining the level of ocular involvement. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and vitreous. OCT can detect early signs of retinal thinning, epiretinal membranes, and other structural abnormalities associated with Stickler Syndrome.

When retinal detachment is suspected, B-scan ultrasonography may be used. This imaging modality enables the ophthalmologist to see the retina and vitreous in greater detail, even when direct visualization is difficult due to media opacities like cataracts or vitreous hemorrhage. B-scan ultrasonography can confirm the presence of a retinal detachment and help guide the surgical decision-making process.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is an important diagnostic tool for confirming the diagnosis of Stickler Syndrome and determining the specific gene mutation. Given Stickler Syndrome’s genetic heterogeneity, where mutations in different collagen-related genes can cause similar clinical manifestations, genetic testing aids in determining the exact cause and guiding management strategies, such as genetic counseling for the patient and their family.

Genetic testing usually entails sequencing the genes most commonly linked to Stickler Syndrome, such as COL2A1, COL11A1, and COL11A2. Given Stickler Syndrome’s autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, identifying a pathogenic mutation in one of these genes can confirm the diagnosis and provide information about the potential risks for other family members. This means that each child of an affected individual has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and thus the condition.

In some cases, a more comprehensive genetic panel may be used to rule out other syndromic forms of hereditary myopia or connective tissue disorders with similar ocular characteristics. While genetic testing can confirm a diagnosis, it is not always required for clinical management of ocular manifestations, but it is critical for a thorough understanding of the illness.

Differential Diagnosis

Another important aspect of diagnosing Stickler Syndrome is distinguishing it from other conditions with similar ocular and systemic symptoms. The differential diagnosis may include Marfan Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and other syndromic forms of myopia with systemic connective tissue involvement.

Marfan Syndrome, for example, can cause high myopia and lens dislocation, but it is most commonly associated with an aortic aneurysm and other systemic characteristics such as tall stature and long limbs. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, particularly the hypermobile type, can cause myopia and vitreous abnormalities, but it is more often associated with joint hypermobility and skin elasticity than the severe vitreoretinal complications seen in Stickler Syndrome.

A thorough clinical evaluation, accompanied by imaging studies and genetic testing, is required to differentiate Stickler Syndrome from these and other conditions, ensuring that the patient receives the best possible care and management.

Ophthalmic Screening for At-Risk Family Members

Given the hereditary nature of Stickler Syndrome, it is critical to screen family members who may be at risk, especially children of affected individuals. Ophthalmic screening should include a thorough eye exam, with a focus on detecting early signs of high myopia, vitreous degeneration, and retinal abnormalities. Early detection enables prompt intervention and close monitoring, which can help avoid the most serious complications, such as retinal detachment.

Ongoing Monitoring

Individuals diagnosed with Stickler Syndrome require ongoing ophthalmic monitoring. Given the progressive nature of the ocular manifestations, regular eye exams are required to detect changes in the vitreous, retina, or other ocular structures. This is especially important for detecting retinal tears or detachments early, so they can be treated quickly to preserve vision.

The severity of the ocular manifestations and the specific risks associated with the patient’s genetic mutation will determine the frequency of follow-up visits. People with a history of retinal detachment, for example, may need more frequent monitoring than those with mild myopia.

Stickler Syndrome Management: Focus on Vision

Stickler Syndrome, particularly its ocular manifestations, necessitates a comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach. Early intervention is critical for preventing or minimizing vision loss, and management strategies must be tailored to the syndrome’s specific ocular complications.

Treatment of Myopia and Refractive Errors

Stickler Syndrome’s earliest and most common ocular manifestation is high myopia. Corrective lenses, such as glasses or contact lenses, are commonly used in management to improve visual acuity. Regular eye exams are required to track the progression of myopia and adjust prescriptions accordingly. In some cases, eligible patients may be considered for refractive surgery, such as LASIK or photorefractive keratectomy (PRK), to reduce their dependence on corrective lenses. However, because of the structural abnormalities associated with Stickler Syndrome, such as thin sclerae, these surgical options are usually approached with caution and reserved for those with stable refractive errors and no significant retinal pathology.

Management of Retinal Detachments

Stickler Syndrome has several serious and vision-threatening complications, including retinal detachment. Prompt surgical intervention is required to repair the detachment and avoid permanent vision loss. Several surgical techniques exist, including:

- Scleral Buckling This procedure involves wrapping a silicone band around the eye to indent the sclera and relieve traction on the retina. This method is especially useful for treating detachments caused by retinal tears or holes.

- Pars Plana Vitrectomy (PPV): This procedure involves removing the vitreous gel to relieve traction on the retina. Vitrectomy is frequently combined with laser or cryotherapy to seal retinal tears, and gas or silicone oil may be used to aid in the reattachment of the retina.

- Pneumatic Retinopexy: This less invasive procedure involves injecting a gas bubble into the vitreous cavity to press the retina against the eye’s wall, allowing the tears to seal using laser or cryotherapy. It is most commonly used for smaller, simpler detachments.

Postoperative care after retinal detachment surgery is critical, with patients frequently required to maintain specific head positions to ensure proper retinal reattachment. Regular follow-up appointments are required to monitor for complications, such as recurrent detachment or cataract formation, which can occur following vitrectomy.

Treatment of Vitreous Degeneration

Vitreous degeneration, a common feature of Stickler Syndrome, raises the risk of retinal tears and detachments. While there is no direct treatment for vitreous degeneration, managing the complications is critical. Preventative measures, such as avoiding activities that could worsen vitreoretinal traction, may be recommended. Regular eye exams with careful monitoring of the retina and vitreous are required for the early detection of tears or detachment, which can then be treated promptly.

Cataract Management

Cataracts often appear earlier in people with Stickler Syndrome than in the general population. When cataracts severely impair vision, cataract surgery may be required. The clouded lens is removed and replaced with an artificial intraocular lens (IOL). Given the possibility of additional ocular complications in Stickler Syndrome, such as retinal detachment or glaucoma, cataract surgery in these patients necessitates meticulous planning and specialized techniques to reduce the risk of postoperative complications.

Management of Glaucoma

Glaucoma, while less common in Stickler Syndrome, necessitates close monitoring of intraocular pressure (IOP). To reduce IOP, topical medications such as prostaglandin analogs, beta-blockers, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may be used. In cases where medical treatment is insufficient, surgical options such as trabeculectomy or the implantation of glaucoma drainage devices may be required to prevent optic nerve damage and preserve vision.

Ongoing Monitoring and Preventive Care

Given the progressive nature of Stickler Syndrome’s ocular manifestations, an ophthalmologist must provide ongoing monitoring. Regular eye exams, usually once a year but more frequently depending on the severity of the condition, are critical for detecting new or worsening complications. Early intervention is critical for preserving vision and improving long-term outcomes.

In addition to ophthalmic care, a multidisciplinary approach that includes genetic counseling, audiology, orthopedics, and other specialties is required to manage the systemic aspects of Stickler Syndrome. Stickler Syndrome families should seek genetic counseling to better understand inheritance patterns, risks to future offspring, and the importance of early screening and diagnosis.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Stickler Syndrome: A Guide for Clinicians and Patients” by Wendy K. Chung and Richard R. Roach: This comprehensive book provides detailed information on the diagnosis, management, and genetic aspects of Stickler Syndrome, making it a valuable resource for both healthcare providers and patients.

- “Stickler Syndrome: An Overview for Parents and Families” by Dr. Jane L. Barrow: Written specifically for families, this book offers an accessible overview of Stickler Syndrome, including practical advice on managing the condition’s ocular and systemic manifestations.

Organizations

- The Stickler Involved People (SIP): An international nonprofit organization that offers support, resources, and information for individuals and families affected by Stickler Syndrome. SIP also facilitates connections with medical experts and advocates for research into better treatments.

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD): Provides detailed information on Stickler Syndrome and offers support services for patients and families dealing with rare diseases, including access to patient advocacy and educational resources.