Punctate Inner Choroidopathy (PIC) is a rare inflammatory ocular condition that primarily affects young to middle-aged women, most of whom are myopic (nearsighted). PIC is part of a larger group of conditions known as “white dot syndromes,” which are defined by multiple, small, white lesions affecting the retina and choroid, the vascular layer of the eye that lies between the retina and the sclera. Unlike other white dot syndromes, PIC affects only the inner layers of the choroid and the outer retina, resulting in the formation of small, punched-out lesions or spots.

Epidemiology

PIC is an uncommon condition, with the majority of cases reported in young myopic women aged 20 to 40. Men are less likely to develop the condition, and it is uncommon in non-myopic individuals. PIC’s exact prevalence is unknown due to its rarity and the risk of underdiagnosis, particularly in its early stages. However, it is more commonly recognized in populations where myopia is prevalent.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The exact cause of PIC is unknown, but it is believed to be an autoimmune or inflammatory disorder. Some researchers believe it is caused by an inappropriate immune response, in which the body’s immune system incorrectly attacks its own tissues, in this case the inner choroid and outer retina. Environmental factors, such as viral infections, have also been suggested as potential triggers, but definitive evidence is lacking.

PIC is frequently associated with other similar inflammatory conditions, such as multifocal choroiditis (MFC) and various forms of white dot syndrome. The absence of significant vitritis (inflammation of the vitreous humor), which is common in other related conditions, distinguishes PIC. In PIC, inflammation primarily affects the inner choroid and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), a pigmented cell layer just outside the neurosensory retina that feeds retinal visual cells.

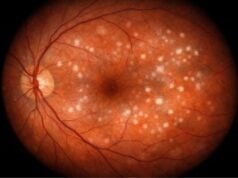

The presence of multiple, small, yellow-white lesions scattered across the posterior pole of the retina, primarily in the macular region, which is responsible for central vision, is the hallmark of PIC. These lesions can range in size and number, and they may coalesce over time. In the acute phase, these lesions are active and inflammatory, but as the disease progresses, they may become atrophic, resulting in the formation of chorioretinal scars.

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of PIC vary according to the severity of the condition and the extent of chorioretinal involvement. However, the most common presenting symptom is a sudden decrease in visual acuity, which is frequently associated with the formation of scotomata, which are areas of partial or complete vision loss surrounded by a field of normal vision. Patients may refer to these scotomata as “blind spots” or areas where their vision is blurry or distorted.

Other common symptoms are:

- Photopsia: Patients with PIC frequently experience flashes of light, a symptom known as photopsia, which is usually more noticeable in low-light conditions. This is thought to be linked to an inflammatory process affecting retinal photoreceptor cells.

- Metamorphopsia: This is a visual distortion in which straight lines appear wavy and objects appear larger or smaller than they actually are. Metamorphopsia is usually caused by a disruption in the macula, which is the central area of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision.

- Floaters: Although less common than in other inflammatory conditions, some patients with PIC may experience floaters—small specks or strands that drift through their field of vision. These are usually more noticeable when there is some vitreous involvement, which is minimal in PIC.

Disease course

PIC can take a variety of forms, with some patients experiencing a single episode of inflammation that resolves without causing significant visual impairment, while others may experience recurrent episodes that result in cumulative damage and progressive vision loss. The disease usually begins in one eye, but it can eventually spread to both.

During the acute phase, the inflammatory lesions may be associated with retinal swelling and serous retinal detachment, in which fluid accumulates beneath the retina, causing additional visual distortion and impairment. As the inflammation subsides, the lesions tend to leave chorioretinal scars. These scars are caused by retinal atrophy, which occurs when retinal tissue is damaged or destroyed, resulting in permanent vision loss in the affected areas.

One of the most serious side effects of PIC is the development of choroidal neovascularization (CNV). This happens when new, abnormal blood vessels grow from the choroid into the retina, which is frequently caused by inflammatory damage to the retinal pigment epithelium and Bruch’s membrane, a thin layer of tissue that connects the retina and the choroid. CNV can cause severe and rapid vision loss due to the leakage of fluid or blood into the retina, resulting in additional retinal damage and scarring.

Differential Diagnosis

PIC must be distinguished from other conditions that may produce similar symptoms and clinical findings. Some of the conditions that can be considered in the differential diagnosis are:

- Multifocal Choroiditis (MFC): MFC, like PIC, has multiple chorioretinal lesions, but it is usually associated with significant vitritis, which PIC does not have. MFC lesions are usually larger and more widespread.

- Serpiginous Choroiditis: Unlike PIC, which has discrete, punctate lesions, this condition is characterized by more extensive and contiguous lesions with a serpentine or snake-like pattern.

- Presumed Ocular Histoplasmosis Syndrome (POHS): POHS is associated with exposure to the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum and can cause similar chorioretinal scarring. POHS, on the other hand, is more common in endemic areas and is associated with a history of systemic infection, whereas PIC does not.

- Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy (APMPPE): APMPPE also causes multiple lesions, but they are larger and more widespread in the outer retina and RPE. APMPPE is frequently associated with systemic symptoms such as flu-like illness, which do not occur in PIC.

Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology of PIC is thought to be an autoimmune response targeting the inner choroid and outer retina. This autoimmune attack destroys the retinal pigment epithelium and choroidal capillaries, producing the distinctive punctate lesions seen on clinical examination. The inflammatory process can also damage the overlying photoreceptor cells, resulting in visual symptoms like scotomata and metamorphopsia.

The inflammatory lesions eventually heal, but they frequently leave areas of atrophy where normal retinal and choroidal structures have been destroyed. These atrophic areas correspond to patients’ scotomata and are responsible for some of the permanent visual deficits observed.

CNV is a serious complication in PIC that results from the breakdown of Bruch’s membrane and the RPE, which normally act as barriers to the growth of new blood vessels. When these structures are damaged by inflammation, they lose their ability to prevent abnormal blood vessels from the choroid from growing into the retina. These new vessels are fragile and prone to leakage, causing additional retinal damage and rapid vision loss.

Clinical Variants

While PIC has a fairly consistent presentation, some clinical variations have been identified. In some cases, patients may present with larger lesions similar to those seen in MFC, while others may have a more widespread pattern of inflammation affecting larger areas of the retina and the choroid. These variants could represent a range of diseases rather than separate entities.

Furthermore, PIC can be associated with other systemic autoimmune conditions, such as multiple sclerosis or sarcoidosis, implying that it may be part of a larger autoimmune process in some patients. However, most cases of PIC occur in isolation, with no associated systemic disease.

Methods to Diagnose Punctate Inner Choroidopathy

Punctate Inner Choroidopathy (PIC) is diagnosed through a combination of clinical examination, imaging studies, and, in some cases, laboratory tests to rule out other causes. Given the rarity of PIC and its overlap with other white dot syndromes, an accurate diagnosis is critical for guiding appropriate treatment and distinguishing PIC from potentially more serious conditions.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing PIC is a thorough clinical examination that includes a detailed patient history as well as a comprehensive eye examination. The patient’s history should include information about the onset and duration of symptoms, any associated systemic symptoms, and a history of previous eye conditions or autoimmune diseases. Myopia is a common feature in PIC patients, so any history of nearsightedness should be noted.

The ophthalmologist will use slit-lamp biomicroscopy to examine the anterior segment of the eye and indirect ophthalmoscopy to assess the posterior segment, which includes the retina and choroid. The presence of multiple, small, yellow-white lesions in the posterior pole, particularly in the macular region, is the hallmark of PIC on ophthalmoscopy. These lesions are usually round or oval and can vary in size. In the acute phase, the lesions may appear more inflamed and be associated with retinal swelling or serous retinal detachments. The lesions may eventually become atrophic, resulting in chorioretinal scars.

Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT)

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid. OCT is especially useful in PIC for determining the extent of retinal and choroidal involvement, as well as tracking disease progression and response to treatment.

OCT scans of PIC patients typically reveal disruptions in the outer retinal layers, particularly the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and the photoreceptor layer. These disruptions correspond to the punctate lesions observed during clinical examination. OCT can also detect subretinal fluid, which may indicate the presence of a serous retinal detachment, which is common during the acute phase of PIC. Furthermore, OCT can detect areas of retinal thinning or atrophy, which are signs of long-term lesions that have caused chorioretinal scarring.

One of the most important applications of OCT in PIC is to detect choroidal neovascularization (CNV). OCT angiography (OCT-A), a specialized type of OCT, can visualize blood flow in the retinal and choroidal vasculature without the use of dye injection. This enables the early detection of CNV, which is critical for timely intervention and avoiding severe vision loss.

Fundal Fluorescein Angiography (FFA)

Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA) is another useful imaging tool for diagnosing PIC. FFA is performed by injecting fluorescein dye intravenously into the blood vessels of the retina and choroid. As the dye circulates, photographs are taken sequentially to show the retinal and choroidal vasculature.

In PIC, FFA can reveal early hyperfluorescence associated with active inflammatory lesions, which may later become hypofluorescent as they atrophic. FFA is especially useful for identifying CNV because abnormal blood vessels typically leak dye, resulting in late-phase hyperfluorescence. This leakage indicates active CNV and can inform treatment decisions.

Indocyanine green angiography (ICGA)

Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA) is a complementary imaging technique to FFA that improves choroidal circulation visualization. ICGA employs indocyanine green dye, which fluoresces in the infrared spectrum, allowing it to penetrate the retinal pigment epithelium and reveal deeper choroidal structures.

In PIC, ICGA can reveal choroidal lesions that would not be visible on FFA, especially when the RPE is intact and obscures the view of the underlying choroid. ICGA is also useful for detecting subclinical CNV and determining the extent of choroidal involvement in PIC.

Autofluorescence Imaging

Autofluorescence imaging is a non-invasive technique that detects the natural fluorescence of lipofuscin, a byproduct of photoreceptor cell metabolism that accumulates in the RPE. In PIC, autofluorescence imaging can detect areas of RPE damage or atrophy, which appear as decreased autofluorescence. This imaging modality is especially useful for monitoring the progression of PIC and detecting early signs of retinal damage before they become clinically noticeable.

Visual Field Testing

Visual field testing is an important diagnostic tool in PIC because it can identify and quantify scotomata, or areas of vision loss, which are a common symptom of the condition. Automated perimetry, such as Humphrey visual field testing, is commonly used to map the visual field and determine the extent and location of scotomata.

Visual field testing in PIC typically reveals central or paracentral scotomata that correspond to the location of chorioretinal lesions. Monitoring changes in the visual field over time can help assess disease progression and treatment efficacy.

Lab Tests

While PIC is primarily diagnosed based on clinical and imaging findings, laboratory tests may be used to rule out other conditions with similar symptoms. Serological tests for infectious diseases, such as syphilis or tuberculosis, may be performed to rule out these as potential causes of chorioretinitis. Tests for autoimmune markers, such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or rheumatoid factor (RF), may also be performed if an underlying systemic autoimmune disorder is suspected.

Punctate Inner Choroidopathy Treatment

Punctate Inner Choroidopathy (PIC) management is individualized based on the severity of the disease and the presence of complications such as choroidal neovascularization. The primary treatment goals are to reduce inflammation, avoid vision-threatening complications, and maintain visual function. Given the chronic nature of PIC, long-term follow-up and monitoring are frequently required.

Corticosteroid Treatment

Corticosteroids are the primary treatment for PIC, particularly during acute inflammatory episodes. They effectively reduce inflammation and protect the retina and choroid from further damage. Corticosteroids can be administered in a variety of ways:

- Oral Corticosteroids: Prednisone is a common prescription for acute inflammation. The severity of the condition determines the dose and duration of treatment. Typically, a high dose is given at first, followed by a gradual tapering over several weeks or months to reduce the risk of reoccurrence.

- Periocular or Intravitreal Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids can be injected directly into the periocular space (around the eye) or intravitreally (into the vitreous cavity) for patients who are unable to tolerate systemic steroids or for more localized treatment. These injections offer targeted treatment with fewer systemic side effects. Triamcinolone acetonide is one of the most commonly used agents.

- Topical Corticosteroids: Corticosteroid eye drops can be used to manage ocular surface inflammation in mild cases or as an adjunct to systemic therapy, but they are generally less effective for treating posterior segment inflammation associated with PIC.

Immunomodulatory Therapy

Immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) may be considered for patients with recurrent or chronic PIC who require long-term management or who suffer from significant corticosteroid side effects. IMT involves the use of immune-modulating drugs to reduce inflammation and prevent further tissue damage. Commonly used agents include:

- Azathioprine: An immunosuppressant that inhibits the proliferation of immune cells, thereby reducing inflammation.

- Mycophenolate Mofetil: Another immunosuppressant that effectively controls inflammation in PIC while reducing corticosteroid use.

- Cyclosporine: Cyclosporine is a calcineurin inhibitor that inhibits T-cell activation, thereby reducing inflammation.

- Biologic Agents: In more severe cases, biologic agents such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs (for example, infliximab, adalimumab) may be used. These agents target specific inflammatory pathways and can be extremely effective in reducing inflammation, particularly in patients with refractory PIC.

Treatment of Choroidal Neovascularization (CNV)

CNV is a serious complication of PIC that requires immediate treatment to avoid severe vision loss. The standard treatment for CNV in PIC is an intravitreal injection of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents. These medications inhibit the formation of abnormal blood vessels and reduce leakage, stabilizing vision and preventing further retinal damage.

- Anti-VEGF Therapy: Ranibizumab (Lucentis), aflibercept (Eylea), and bevacizumab (Avastin) are common treatments for CNV associated with PIC. These medications are given intravitreal injections, usually once a month, until the CNV stabilizes. Once the condition is under control, injection frequency can be reduced, but continuous monitoring is required to detect recurrences.

- Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): If anti-VEGF therapy is ineffective or contraindicated, photodynamic therapy should be considered. PDT entails administering a photosensitizing agent intravenously before activating the retina with a specific wavelength of light. This treatment selectively targets abnormal blood vessels, reducing leakage and preventing additional damage.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Long-term monitoring is critical in the management of PIC due to its chronic nature and the risk of recurrent inflammation or complications such as CNV. Regular follow-up appointments with an ophthalmologist are required to monitor disease progression and adjust treatment as needed. Visual acuity testing, OCT, and, if necessary, angiography to assess the retina and choroid are common follow-up procedures.

In addition to medical care, patients with PIC may benefit from visual aids, low vision services, and psychological support, especially if they have significant vision loss. These supportive measures can help patients improve their quality of life and cope with any visual impairments.

Patient Education and Lifestyle Modification

It is critical to educate patients about the nature of PIC, the importance of following treatment instructions, and the need for regular follow-up. Patients should be aware of the warning signs of potential complications, such as a sudden increase in floaters, flashes of light, or a decrease in vision, which could indicate the development of CNV or other issues requiring immediate medical attention.

Lifestyle changes, such as wearing protective eyewear to reduce the risk of eye trauma, quitting smoking, and managing any underlying systemic conditions, may also help manage PIC and prevent exacerbations.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “The Retinal Atlas” by Lawrence A. Yannuzzi – This comprehensive atlas covers a wide range of retinal diseases, including PIC, providing detailed images and descriptions that are invaluable for both patients and clinicians.

- “Fundamentals of Clinical Ophthalmology: Uveitis and Immunological Disorders” by C. Stephen Foster and Albert T. Vitale – This book offers an in-depth look at various inflammatory ocular conditions, including PIC, with a focus on clinical management and treatment strategies.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) – The AAO provides extensive resources on eye diseases, including PIC, offering up-to-date information for both patients and healthcare professionals. AAO Website

- National Eye Institute (NEI) – Part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the NEI offers valuable resources and information on PIC and other eye conditions, promoting research and patient education. NEI Website