The spinal cord is the central highway of the nervous system, responsible for transmitting signals between the brain and the rest of the body. Encased in the protective vertebral column, it orchestrates not only voluntary movement and sensory processing but also mediates critical reflexes and autonomic functions. This in-depth guide explores the intricate anatomy, diverse functions, common disorders, advanced diagnostic techniques, and cutting-edge treatment options related to the spinal cord. Whether you are a healthcare professional or someone eager to enhance your well-being, this comprehensive resource provides essential insights and practical tips for maintaining spinal cord health.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Architecture

- Internal Organization

- Spinal Nerve Distribution

- Vascularization & Blood Supply

- Reflex Mechanisms

- Functional Dynamics

- Common Disorders

- Diagnostic Techniques

- Treatment Interventions

- Nutritional & Supplementary Support

- Lifestyle & Wellness Practices

- Trusted Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Disclaimer & Sharing

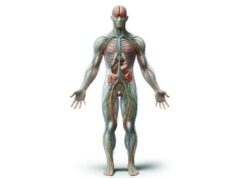

Anatomical Architecture of the Spinal Cord

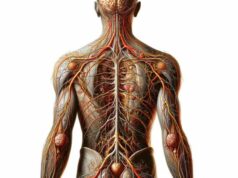

The spinal cord is a complex, elongated structure that serves as the principal conduit for neural signals between the brain and peripheral tissues. Encased within the vertebral column, its design not only provides robust protection but also ensures that the intricate network of nerve fibers remains securely insulated.

Gross Structural Overview

- Length and Segmentation:

In the adult human, the spinal cord measures approximately 45 centimeters (18 inches) in length. It is segmented into five distinct regions—cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccygeal—each corresponding to paired spinal nerves that innervate specific body regions. - Meningeal Encasement:

The spinal cord is shielded by three protective layers known as the meninges: - Dura Mater: The tough, outermost layer that forms a resilient covering.

- Arachnoid Mater: A delicate, web-like middle layer that cushions the cord.

- Pia Mater: The innermost, thin membrane that clings directly to the spinal cord surface.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF):

Residing within the subarachnoid space between the arachnoid and pia maters, cerebrospinal fluid provides both buoyancy and shock absorption, ensuring the spinal cord is cushioned from mechanical impact and helping in the removal of metabolic waste.

This robust anatomical framework is crucial not only for the protection of the spinal cord but also for its efficient functioning as a neural superhighway.

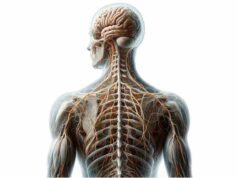

Internal Organization and White/Gray Matter Distribution

Beneath its protective outer layers, the spinal cord features a highly organized internal structure. The central region comprises gray matter, which is surrounded by white matter—each with distinct roles that facilitate neural communication.

Gray Matter Architecture

- Butterfly-Shaped Core:

The gray matter, rich in neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and unmyelinated axons, is arranged in a distinctive butterfly or H-shaped pattern. It is subdivided into: - Dorsal Horns: Primarily responsible for processing sensory information.

- Ventral Horns: Contain motor neurons that dispatch signals to skeletal muscles.

- Lateral Horns: Present mainly in the thoracic and upper lumbar regions, these are involved in autonomic regulation.

White Matter Composition

- Myelinated Axonal Tracts:

Encircling the gray matter, the white matter consists of myelinated nerve fibers that form complex ascending and descending tracts. - Ascending Tracts: These pathways relay sensory data from peripheral receptors to higher brain centers.

- Descending Tracts: They transmit motor commands from the brain to the spinal cord, enabling voluntary movement.

The precise organization of white and gray matter is essential for the rapid transmission of electrical impulses and the integration of complex neural processes.

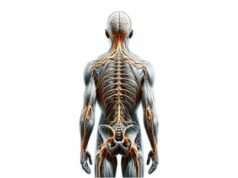

Spinal Nerve Distribution and Segmental Organization

Emerging from the spinal cord are 31 pairs of spinal nerves that form an intricate communication network, linking the central nervous system to the periphery.

Spinal Nerve Structure

- Mixed Nerves:

Each spinal nerve comprises both dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) roots. The dorsal root ganglion, a cluster of sensory neuron cell bodies, lies just outside the cord, while ventral roots carry motor fibers away from the spinal cord. - Segmental Organization:

- Cervical (C1–C8): Innervate the head, neck, shoulders, arms, and hands.

- Thoracic (T1–T12): Provide motor and sensory supply to the chest and upper abdominal regions.

- Lumbar (L1–L5): Serve the lower back, hips, and legs.

- Sacral (S1–S5): Innervate the pelvic region, buttocks, and parts of the legs.

- Coccygeal (Co1): Associated with the tailbone area.

Dermatomes and Myotomes

- Dermatomes:

Specific skin areas are innervated by sensory fibers from a single spinal nerve. Mapping these regions is crucial for diagnosing nerve injuries and localizing lesions. - Myotomes:

These are groups of muscles controlled by motor fibers from a single spinal nerve, helping clinicians assess motor function and detect neuromuscular deficits.

This segmental distribution underpins the spinal cord’s ability to localize and coordinate both sensory and motor functions throughout the body.

Vascularization and Blood Supply

A robust vascular network is essential for delivering nutrients and oxygen while removing metabolic waste from the spinal cord.

Arterial Supply

- Anterior Spinal Artery:

Originating from the vertebral arteries, the anterior spinal artery runs along the front of the spinal cord, supplying approximately the anterior two-thirds of the cord’s tissue. - Posterior Spinal Arteries:

These paired arteries, which also arise from the vertebral arteries, supply the posterior one-third of the spinal cord.

Venous Drainage

- Venous Plexus:

The spinal cord is drained by a network of veins that converge into the internal vertebral venous plexus, which subsequently empties into the systemic venous circulation.

The well-coordinated vascular system is fundamental to the spinal cord’s vitality, ensuring that neural tissue remains healthy and functionally intact.

Reflex Mechanisms and Neural Circuitry

Reflex arcs are one of the most fascinating aspects of spinal cord physiology, enabling rapid, involuntary responses that protect the body from harm.

Components of Reflex Arcs

- Basic Structure:

A typical reflex arc consists of a sensory receptor, a sensory neuron, one or more interneurons, and a motor neuron. - Monosynaptic Reflexes:

In these simple circuits, the sensory neuron directly synapses with a motor neuron. The knee-jerk reflex is the classic example of a monosynaptic reflex. - Polysynaptic Reflexes:

More complex reflexes involve additional interneurons that allow for modulation and integration of multiple signals, such as the withdrawal reflex when encountering a painful stimulus.

Functional Importance

- Protection and Homeostasis:

Reflexes are vital for immediate responses to dangerous stimuli, helping to prevent injury by bypassing slower, conscious processing. - Postural Control:

Reflex mechanisms also contribute to maintaining posture and balance, ensuring that the body responds appropriately to changes in position.

This rapid-response system underscores the spinal cord’s critical role in both protective reflexes and the fine-tuning of motor functions.

Functional Dynamics of the Spinal Cord

Beyond its structural complexity, the spinal cord plays a central role in coordinating a range of physiological functions necessary for daily life.

Signal Transmission and Neural Integration

- Sensory Pathways:

Sensory signals from peripheral receptors enter the spinal cord via the dorsal roots. These signals travel through ascending tracts in the white matter, reaching the brain where they are interpreted as touch, temperature, pain, and proprioception. - Motor Pathways:

Descending tracts, notably the corticospinal pathway, transmit motor commands from the brain’s motor cortex to the spinal cord, where they are relayed via ventral roots to the appropriate skeletal muscles.

Reflexive and Autonomous Functions

- Reflex Actions:

Reflex arcs enable the spinal cord to generate rapid, automatic responses without direct brain involvement. This is crucial for protective reflexes, such as quickly retracting a limb from a painful stimulus. - Autonomic Integration:

Although primarily associated with voluntary movement, the spinal cord also contains lateral horn regions that participate in autonomic regulation, influencing functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, and digestion.

Brain-Spinal Cord Coordination

- Bidirectional Communication:

The spinal cord acts as a relay station, ensuring that sensory information is efficiently transmitted to the brain while conveying motor commands back to the muscles. - Preprocessing of Sensory Data:

Some sensory information is processed at the spinal level, which helps filter and prioritize signals before they reach higher brain centers for conscious analysis.

The dynamic interplay between these processes ensures that the spinal cord remains integral to both rapid reflexive actions and the controlled execution of voluntary movements.

Common Spinal Cord Disorders

Given its central role in bodily functions, the spinal cord is susceptible to a range of disorders that can disrupt communication between the brain and the body. This section reviews some of the most prevalent conditions affecting the spinal cord.

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI)

- Overview:

SCI occurs when trauma—such as a car accident, fall, or sports injury—damages the spinal cord, leading to partial or complete loss of motor and sensory functions below the injury level. - Types:

- Complete Injury: Total loss of function below the level of injury.

- Incomplete Injury: Partial preservation of sensory or motor function.

- Symptoms and Treatment:

Symptoms include paralysis, loss of sensation, and impaired autonomic control. Immediate management involves stabilization, followed by rehabilitation therapies, medications, and sometimes surgery to prevent further damage.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Pathophysiology:

MS is an autoimmune condition in which the immune system attacks the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers, including those in the spinal cord, leading to inflammation and demyelination. - Clinical Manifestations:

Patients may experience muscle weakness, impaired coordination, sensory disturbances, and visual problems. - Treatment Approaches:

While there is no cure, disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), corticosteroids, and supportive physical therapy help manage symptoms and slow progression.

Spinal Stenosis

- Definition:

Spinal stenosis is characterized by a narrowing of the spinal canal, which compresses the spinal cord and nerve roots. - Symptoms:

Common signs include back pain, numbness, tingling, and in severe cases, impaired bladder or bowel function. - Management Options:

Treatment may involve physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, and, if necessary, surgical decompression procedures such as laminectomy or foraminotomy.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

- Disease Characteristics:

ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects motor neurons in both the brain and spinal cord, leading to muscle wasting and eventual paralysis. - Symptom Progression:

Early symptoms include muscle twitching and weakness, progressing to severe motor deficits and respiratory compromise. - Treatment Strategies:

Medications like riluzole and edaravone may slow disease progression, while supportive care—including physical, speech, and respiratory therapies—is essential for managing symptoms.

Herniated Disc

- Mechanism:

A herniated disc occurs when the soft, gel-like nucleus of an intervertebral disc protrudes through a tear in its outer layer, potentially compressing nearby spinal nerves. - Clinical Presentation:

Symptoms may include localized pain, radiculopathy (radiating pain), numbness, and weakness in the affected limb. - Treatment:

Initial management involves conservative measures such as physical therapy, pain relief medications, and epidural steroid injections; surgical options may be considered for refractory cases.

Spinal Tumors

- Overview:

Spinal tumors can be either primary (originating within the spinal cord) or metastatic (spreading from other parts of the body). They can compress the spinal cord and disrupt normal function. - Symptoms and Diagnosis:

Patients may present with localized pain, neurological deficits, and loss of function below the tumor level. Treatment typically involves surgical resection, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy depending on the tumor type.

Syringomyelia

- Definition:

Syringomyelia is characterized by the formation of a fluid-filled cyst, or syrinx, within the spinal cord that can expand over time and damage neural tissue. - Symptoms:

Common manifestations include pain, muscle weakness, stiffness, and sensory disturbances, particularly in the upper extremities. - Management:

Treatment may involve monitoring, pain management, and surgical interventions—such as shunting procedures—to drain the syrinx and relieve pressure.

Diagnostic Techniques for Spinal Cord Disorders

Accurate and timely diagnosis is paramount for effective management of spinal cord conditions. A multifaceted diagnostic approach is often employed, integrating clinical evaluations with advanced imaging and electrophysiological studies.

Clinical History and Physical Examination

- Detailed Medical History:

Clinicians gather comprehensive information about symptom onset, progression, previous injuries, family history, and lifestyle factors to establish a clinical context. - Neurological Examination:

A thorough assessment includes testing motor strength, sensory function, reflexes, and coordination. This evaluation helps localize the lesion and guide further diagnostic testing.

Imaging Modalities

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is the gold standard for visualizing soft tissue structures. It provides high-resolution images of the spinal cord, revealing lesions, compressive pathologies, inflammation, and demyelination. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT imaging offers detailed cross-sectional views of bony structures, helping detect fractures, degenerative changes, and spinal canal narrowing. - X-rays:

Conventional radiography is used to assess spinal alignment, detect fractures, and evaluate degenerative joint disease.

Electrophysiological Studies

- Electromyography (EMG):

EMG measures the electrical activity of muscles, identifying abnormalities in neuromuscular transmission and muscle function. It is crucial in diagnosing conditions like ALS and peripheral neuropathies. - Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS):

NCS evaluate the speed and amplitude of electrical signals along peripheral nerves, helping to detect nerve compression, demyelination, and axonal loss.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood Tests:

Routine panels and specific markers (e.g., inflammatory markers, vitamin levels, autoantibodies) can reveal underlying metabolic, autoimmune, or infectious causes. - Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap):

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) obtained via lumbar puncture can detect infections, inflammatory conditions, or malignancies affecting the spinal cord.

Biopsy Procedures

- Nerve and Muscle Biopsies:

Tissue samples obtained from affected nerves or muscles are examined microscopically to identify inflammation, degeneration, or neoplastic processes. These biopsies provide definitive pathological insights in complex cases.

Specialized Functional Tests

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs):

In disorders like ALS, PFTs assess respiratory muscle strength and lung function. - Swallowing Studies:

These evaluations help determine the integrity of the neuromuscular mechanisms involved in swallowing, particularly in patients with neuromuscular compromise.

The integration of these diagnostic modalities allows for a comprehensive evaluation of spinal cord disorders, ensuring that treatment strategies are tailored to each individual’s needs.

Treatment Approaches and Interventions

Management of spinal cord disorders requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines medical, surgical, and rehabilitative strategies. Treatments are tailored based on the specific condition, its severity, and the patient’s overall health.

Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Management

- Acute Stabilization:

Immediate immobilization of the spine is critical to prevent further damage. High-dose steroid therapy may be administered within a narrow time window to reduce inflammation. - Surgical Interventions:

Surgery may be necessary to stabilize the spine, remove bone fragments, or decompress the spinal cord. - Rehabilitation:

A comprehensive rehabilitation program—including physical and occupational therapy—is essential for maximizing functional recovery. Assistive devices and adaptive techniques are introduced gradually. - Advanced Therapies:

Emerging treatments such as stem cell therapy and neuroprosthetics are under investigation to promote neural repair and improve motor function.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Management

- Disease-Modifying Therapies (DMTs):

Medications like interferons, glatiramer acetate, and newer oral agents help reduce the frequency and severity of relapses. - Symptom Management:

Corticosteroids are used during acute exacerbations, while muscle relaxants and pain medications alleviate spasticity and discomfort. - Rehabilitation and Support:

Physical and occupational therapy, combined with lifestyle modifications, enhance mobility and quality of life.

Spinal Stenosis Treatment

- Conservative Management:

Initial treatment includes NSAIDs, muscle relaxants, and corticosteroid injections to reduce pain and inflammation. Physical therapy is used to improve flexibility and strengthen supporting muscles. - Surgical Options:

Procedures such as laminectomy, foraminotomy, or spinal fusion may be indicated for severe cases to decompress neural structures and stabilize the spine.

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Support

- Pharmacological Therapy:

Medications such as riluzole and edaravone may modestly slow the progression of ALS. - Multidisciplinary Support:

A team of neurologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and respiratory specialists work together to address the various challenges associated with ALS. - Assistive Technologies:

Adaptive devices and communication aids are introduced as the disease progresses, helping maintain quality of life.

Herniated Disc Management

- Conservative Care:

Initial treatment often involves rest, physical therapy, and pain management with NSAIDs or corticosteroids. Epidural steroid injections may be utilized to reduce inflammation. - Surgical Interventions:

In cases where conservative treatments fail, surgical options such as discectomy or laminectomy may be recommended to relieve nerve compression.

Spinal Tumors Treatment

- Surgical Resection:

Removal of the tumor is often the first step to relieve pressure on the spinal cord. - Adjuvant Therapies:

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy are used in malignant cases to control tumor growth and prevent metastasis. - Multidisciplinary Management:

Ongoing rehabilitation and supportive care are crucial in managing neurological deficits resulting from tumor treatment.

Syringomyelia Intervention

- Monitoring and Observation:

Regular imaging is used to monitor the size and progression of the syrinx. - Surgical Drainage:

Procedures such as syrinx drainage or shunting may be performed to alleviate pressure and preserve spinal cord function. - Addressing Underlying Causes:

In cases associated with Chiari malformation, decompression surgery may be necessary.

Nutritional and Supplementary Support for Spinal Health

A balanced diet combined with targeted nutritional supplements plays a significant role in supporting spinal cord health, enhancing nerve repair, and reducing inflammation.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Benefits:

Omega-3 fatty acids are renowned for their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to promote neuroprotection. They help support the integrity of nerve membranes and may slow the progression of neurodegenerative changes. - Sources:

Rich sources include fatty fish, flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts.

Vitamin B12

- Essential Role:

Vitamin B12 is critical for the maintenance of the myelin sheath and overall nerve health. Deficiencies can lead to neurological dysfunction and spinal cord degeneration. - Sources and Supplementation:

Found in animal products such as meat, dairy, and eggs, B12 supplements are especially important for individuals on a vegetarian or vegan diet.

Vitamin D

- Supportive Effects:

Vitamin D modulates immune responses and supports musculoskeletal health. It may also help reduce inflammation in conditions like MS. - Sources:

Sunlight exposure, fortified foods, and supplements can help maintain optimal vitamin D levels.

Curcumin (Turmeric)

- Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties:

Curcumin has potent anti-inflammatory effects and helps neutralize oxidative stress, thereby protecting spinal cord tissue from damage. - Usage:

It can be incorporated into the diet as a spice or taken as a supplement, often with black pepper extract to enhance absorption.

Magnesium

- Neuromuscular Function:

Magnesium is vital for proper muscle and nerve function, reducing muscle cramps and supporting overall spinal health. - Sources:

Leafy greens, nuts, seeds, and whole grains are excellent dietary sources, and supplements can be considered if necessary.

Alpha Lipoic Acid

- Antioxidant Support:

This powerful antioxidant reduces oxidative stress and improves nerve conduction. It is particularly beneficial for managing diabetic neuropathy. - Supplementation:

Alpha lipoic acid supplements are available and can be an important adjunct in nerve health maintenance.

Coenzyme Q-10 (CoQ10)

- Energy Production and Neuroprotection:

CoQ10 supports mitochondrial function and provides antioxidant protection, which is crucial for high-energy tissues like the spinal cord. - Sources:

It is available in supplement form and is also found in small amounts in foods such as fatty fish and organ meats.

Acetyl-L-Carnitine

- Nerve Regeneration and Pain Relief:

This compound aids in the regeneration of damaged nerves and helps alleviate neuropathic pain, improving overall nerve function. - Usage:

Often taken as a supplement to support energy metabolism in nerve cells.

Probiotics

- Gut-Brain Connection:

A healthy gut microbiome supports overall immune function and nutrient absorption, which indirectly benefits the nervous system. - Sources:

Yogurt, kefir, and fermented vegetables are excellent natural sources of probiotics.

L-theanine

- Calming Effects and Cognitive Support:

L-theanine promotes relaxation without sedation, reducing stress-related damage to nerves and enhancing cognitive clarity. - Supplementation:

It is commonly available in supplement form and is also found in green tea.

Lifestyle and Wellness Practices for Spinal Cord Health

Maintaining spinal cord health requires a holistic approach that combines proper nutrition, regular physical activity, and healthy lifestyle choices. Here are some best practices to support a robust and resilient spinal cord:

- Balanced Diet:

Consume a variety of fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains to ensure a steady intake of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that support nerve function. - Adequate Hydration:

Aim for at least 8 cups of water per day to facilitate optimal cellular function and maintain the health of spinal tissues. - Regular Exercise:

Engage in moderate-intensity activities such as walking, swimming, or yoga to enhance blood flow, improve flexibility, and strengthen the muscles that support the spine. - Weight Management:

Maintaining a healthy weight reduces stress on the spine and lowers the risk of degenerative conditions such as herniated discs and spinal stenosis. - Proper Ergonomics:

Use ergonomic furniture, maintain correct posture, and ensure that your work environment supports spinal alignment. Adjustable chairs, standing desks, and lumbar supports can make a significant difference. - Stress Reduction:

Chronic stress can negatively impact the nervous system. Incorporate mindfulness practices, meditation, and deep breathing exercises to manage stress effectively. - Avoid Smoking and Limit Alcohol:

Smoking restricts blood flow and accelerates degenerative processes, while excessive alcohol can contribute to nerve damage. Moderation is key. - Protect Against Injury:

Always use proper lifting techniques, wear protective gear during physical activities, and engage in exercises that enhance core stability. - Sleep Hygiene:

Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep each night. A supportive mattress and proper pillow alignment are critical for spinal recovery and overall health. - Regular Medical Check-Ups:

Routine visits to your healthcare provider allow for early detection and management of spinal conditions. Regular screenings can prevent minor issues from becoming severe.

Implementing these lifestyle practices can help preserve spinal cord function, improve overall well-being, and reduce the risk of developing chronic spinal disorders.

Trusted Resources for Spinal Cord Information

For individuals seeking to deepen their understanding of spinal cord health, numerous reputable resources are available. The following books, academic journals, and mobile applications offer authoritative insights and up-to-date research on spinal cord disorders, treatments, and rehabilitation strategies.

Books

- “The Spinal Cord Injury Handbook: For Patients and Families” by Richard C. Senelick

An essential guide that provides detailed information on spinal cord injuries, treatment options, and strategies for adapting to life after injury. - “Spinal Cord Injury: Functional Rehabilitation” by Martha Freeman Somers

Focuses on rehabilitation techniques and therapeutic strategies designed to maximize recovery and improve quality of life for individuals with spinal cord injuries. - “Back in Control: A Surgeon’s Roadmap Out of Chronic Pain” by David Hanscom

Offers insights into managing chronic pain through non-surgical methods, emphasizing lifestyle changes, stress reduction, and mindful approaches to spinal health.

Academic Journals

- Journal of Neurotrauma

Publishes cutting-edge research on spinal cord and brain injuries, providing valuable insights into novel treatment approaches and rehabilitation protocols. - Spine

A leading journal dedicated to spinal disorders, offering peer-reviewed studies on biomechanics, surgical innovations, and non-surgical management of spinal conditions.

Mobile Applications

- MyFitnessPal

A versatile app that tracks nutrition and physical activity, assisting users in maintaining a balanced diet that supports spinal and overall health. - Calm

Provides guided meditations and sleep stories, helping to manage stress and improve sleep quality—both of which are crucial for spinal recovery. - Back Pain Exercises

This app offers specific exercise routines and stretches designed to alleviate back pain and strengthen the muscles supporting the spine.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary role of the spinal cord?

The spinal cord serves as the central conduit for transmitting signals between the brain and the body. It coordinates voluntary movement, processes sensory information, and facilitates rapid reflex actions essential for protecting the body from harm.

How does the spinal cord transmit nerve signals?

Nerve signals travel along the spinal cord via ascending and descending tracts. Sensory information enters through dorsal roots and is sent to the brain, while motor commands from the brain descend through ventral roots to control muscle activity.

What are common symptoms of spinal cord disorders?

Symptoms vary by condition but may include pain, numbness, muscle weakness, loss of coordination, and impaired autonomic functions. In severe cases, paralysis and loss of bladder or bowel control may occur.

How are spinal cord conditions diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical evaluations, imaging studies such as MRI and CT scans, electrophysiological tests (EMG and nerve conduction studies), and sometimes laboratory tests or biopsies to pinpoint the underlying issue.

What lifestyle changes support spinal cord health?

Maintaining a balanced diet, regular exercise, proper ergonomics, stress management, adequate sleep, and routine medical check-ups are essential for preserving spinal cord health and preventing degenerative conditions.

Disclaimer & Sharing

The information provided in this article is intended for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized recommendations and treatment options.

Feel free to share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social platform to help spread awareness and promote spinal cord health.