The ureters are vital, slender muscular tubes that play a crucial role in the urinary system by conveying urine from the kidneys to the bladder. These dynamic structures not only ensure the efficient transport of urine but also protect the upper urinary tract from infections and backflow. In this comprehensive guide, we explore the intricate structure, diverse functions, common disorders, diagnostic approaches, treatment modalities, and lifestyle practices essential for maintaining optimal ureteral health. Whether you’re a healthcare professional or a curious reader, this resource offers a detailed, engaging overview to help you understand and care for these essential conduits.

Table of Contents

- Ureteral Structural Overview

- Physiological Roles and Mechanisms

- Ureteral Pathologies and Disorders

- Diagnostic Modalities for Ureteral Conditions

- Management and Therapeutic Approaches

- Nutritional and Supplement Strategies

- Best Practices for Ureter and Urinary Health

- Authoritative References and Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

Ureteral Structural Overview

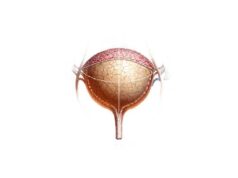

The ureters are anatomically designed to be both resilient and flexible, ensuring the uninterrupted flow of urine from the kidneys to the bladder. This section delves into the layers, segments, blood supply, and variations that define ureteral anatomy.

Detailed Layers and Composition

The wall of the ureter is composed of three principal layers, each contributing to its overall function:

- Mucosal Layer (Urothelium):

The innermost lining, known as the urothelium or transitional epithelium, is highly specialized. Its unique ability to stretch accommodates varying volumes of urine without compromising its barrier function. Beneath the urothelium lies the lamina propria—a supportive connective tissue layer enriched with blood vessels and nerve fibers, which provides nourishment and sensory input. - Muscularis Layer:

Surrounding the mucosa is the muscularis, consisting of smooth muscle fibers organized in two distinct layers. An inner longitudinal layer works in concert with an outer circular layer to generate peristaltic waves. These rhythmic contractions are fundamental to propelling urine downward. Notably, the muscularis is thicker in the upper two-thirds of the ureter than in the lower third, thereby enhancing its contractile efficiency. - Adventitial Layer:

The outermost layer, the adventitia, comprises loose connective tissue that anchors the ureter to surrounding structures. This layer also contains small blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerve endings, ensuring the ureter remains well-vascularized and integrated within the broader urinary system.

Segments and Anatomical Course

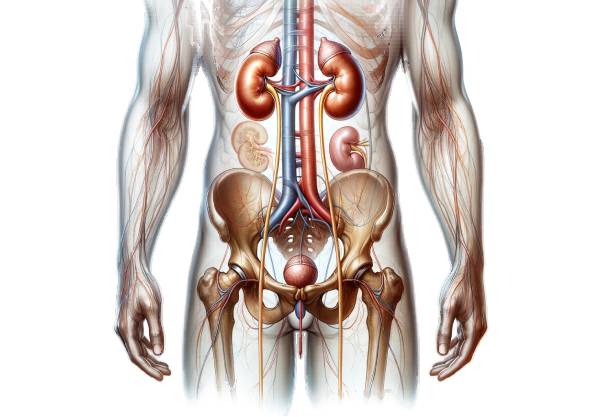

The ureter can be divided into several segments based on its anatomical course:

- Abdominal Ureter:

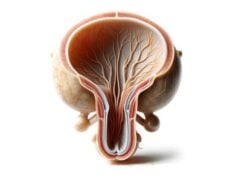

Beginning at the renal pelvis, this segment emerges as urine collects from the kidney’s collecting ducts. It descends retroperitoneally alongside the psoas major muscle, eventually reaching the pelvic brim near the common iliac artery bifurcation. This section is characterized by a robust muscular layer that initiates effective peristalsis. - Pelvic Ureter:

As the ureter enters the pelvic cavity, it curves medially and anteriorly. In males, it lies close to the seminal vesicles and ductus deferens; in females, it is positioned near the ovaries and the broad ligament of the uterus. This segment continues the journey toward the bladder while navigating the complex pelvic anatomy. - Intramural Ureter:

The final segment, embedded within the bladder wall, runs obliquely. This angled entry creates a valve-like mechanism that prevents the backflow of urine (vesicoureteral reflux) during bladder contraction, thus safeguarding the kidneys from potential infections and pressure-related damage.

Vascular Supply and Neural Connections

The ureters receive a diverse blood supply that varies along their length:

- Upper Ureter:

Blood is supplied by branches of the renal arteries, stemming directly from the abdominal aorta. - Middle Ureter:

Here, the gonadal arteries (testicular or ovarian) and branches from the abdominal aorta contribute to the vascular network. - Lower Ureter:

The inferior portion is nourished by branches from the internal iliac arteries, including the superior, uterine, and inferior vesical arteries.

Venous drainage generally mirrors arterial supply, with blood returning via the renal, gonadal, and internal iliac veins. The ureters’ innervation is primarily autonomic. Sympathetic fibers from the renal, aortic, and hypogastric plexuses facilitate peristaltic contractions, while parasympathetic fibers from the pelvic splanchnic nerves modulate muscle tone and pain perception.

Lymphatic Drainage

Efficient lymphatic drainage is critical for immune surveillance and infection prevention. Lymph from the upper ureter drains into the lumbar (aortic) lymph nodes, whereas the middle and lower segments channel lymph to the common, external, and internal iliac nodes. This drainage pattern ensures that pathogens and cellular debris are effectively removed.

Histological Characteristics

Histologically, the ureter is distinguished by its transitional epithelium, which provides both a protective barrier and remarkable elasticity. The underlying lamina propria supports this epithelium with a rich capillary network and interstitial cells. The muscularis, composed of smooth muscle, is essential for generating peristaltic movements, while the adventitia offers structural support and facilitates vascular and neural passage.

Anatomical Variations

While the described anatomy represents the typical ureteral structure, variations do occur. For instance, duplicated ureters—where two ureters drain a single kidney—are congenital anomalies that may predispose individuals to infections or obstructions. Another notable variation is the retrocaval ureter, where the ureter passes behind the inferior vena cava, potentially leading to urinary obstruction and necessitating surgical correction.

Clinical Significance

A comprehensive understanding of ureteral anatomy is vital for diagnosing and treating urological conditions. Detailed knowledge of the ureter’s structure aids in procedures such as ureteral stenting, reimplantation, and the removal of obstructive stones. Moreover, the anatomical relationships and variations of the ureter are crucial considerations in surgical planning to minimize complications and preserve renal function.

Physiological Roles and Mechanisms

The ureters perform several indispensable functions in the urinary system, ensuring the safe and efficient transport of urine while maintaining the sterility and balance of bodily fluids. This section examines the key physiological mechanisms that underlie ureteral function.

Urine Transport via Peristalsis

The primary role of the ureters is to move urine from the kidneys to the bladder. This is achieved through peristalsis—a series of coordinated, wave-like muscular contractions. The smooth muscle layers in the ureteral wall contract rhythmically, generating pressure that propels urine downward. This mechanism is finely tuned; as the ureter expands to accommodate increasing urine volume, the peristaltic waves intensify to ensure continuous flow and prevent urinary stasis.

Prevention of Vesicoureteral Reflux

A critical protective function of the ureters is to prevent the backward flow of urine into the kidneys, a phenomenon known as vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). The intramural segment of the ureter, which traverses the bladder wall at an oblique angle, acts as a one-way valve. When the bladder contracts during urination, the pressure compresses the ureteral lumen, effectively blocking any retrograde movement of urine. This valve-like action is essential for protecting the kidneys from infections and potential damage caused by elevated pressures.

Regulation of Urine Flow

Urine flow through the ureters is influenced by several factors, including the volume of urine produced, hormonal signals, and neural input. Increased fluid intake or the use of diuretics elevates urine production, which in turn enhances peristaltic activity. The autonomic nervous system plays a significant role in this regulation: sympathetic stimulation increases the force and frequency of contractions, while parasympathetic activity modulates and fine-tunes these responses. This dynamic balance ensures that urine is transported efficiently regardless of fluctuations in production.

Maintenance of Urine Sterility

The ureter’s mucosal lining, composed of transitional epithelium, is instrumental in preserving urine sterility. Tight junctions between the epithelial cells form a robust barrier that prevents the passage of bacteria and other pathogens. Additionally, the constant movement of urine acts as a flushing mechanism, reducing the likelihood of microbial colonization and infection. This protective feature is critical for maintaining the overall health of the urinary tract.

Adaptation to Volume and Pressure Variations

One of the remarkable features of the ureters is their ability to adapt to varying urine volumes and pressures. The elastic properties of the transitional epithelium allow the ureter to expand significantly when urine volume increases, without compromising its integrity. This adaptability is essential for preventing leakage and ensuring that even during periods of high urine production or transient obstructions, the flow remains continuous and effective.

Contribution to Fluid and Electrolyte Balance

While the ureters are primarily conduits for urine, they also play a subtle role in maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance within the body. Efficient urine transport ensures that waste products and excess electrolytes are removed promptly, preventing their accumulation. Conversely, any dysfunction in the ureters can lead to fluid retention, electrolyte imbalances, and, in severe cases, renal damage. Therefore, optimal ureteral function is critical for overall homeostasis and metabolic regulation.

Ureteral Pathologies and Disorders

A range of disorders can affect the ureters, impairing their function and potentially leading to significant health complications. This section provides an in-depth look at common ureteral conditions, from obstructive stones to congenital anomalies, highlighting their causes, symptoms, and treatment options.

Ureteral Stones (Urolithiasis)

Ureteral stones, or urolithiasis, are among the most frequently encountered disorders of the ureters. These calculi form in the kidneys and may migrate into the ureter, causing severe pain and obstruction.

- Pathogenesis and Composition:

Stones are composed of various substances, including calcium oxalate, uric acid, struvite, or cystine. Factors such as dehydration, dietary habits, and genetic predisposition can increase the risk of stone formation. - Clinical Presentation:

Patients typically experience renal colic—severe, intermittent flank pain that may radiate to the lower abdomen or groin. Other symptoms include hematuria (blood in the urine), nausea, vomiting, and urinary frequency. - Diagnostic Approach:

Imaging studies, particularly non-contrast computed tomography (CT), are the gold standard for identifying stones. Ultrasound and plain radiographs may also be used, especially in vulnerable populations like pregnant women and children. - Treatment Modalities:

Management ranges from conservative measures—such as increased hydration and pain control—to interventional procedures like extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy. Severe or persistent obstructions may require surgical removal.

Ureteral Strictures

Ureteral strictures are characterized by the narrowing of the ureter, which can impede urine flow and lead to hydronephrosis.

- Etiology:

Strictures may be congenital or acquired due to trauma, surgical interventions, infections, or chronic inflammatory processes. - Symptoms and Signs:

Patients often present with flank pain, recurrent urinary tract infections, and hematuria. Advanced strictures can result in kidney swelling and decreased renal function. - Diagnosis and Management:

Imaging techniques, including intravenous pyelography (IVP) and CT urography, help delineate the extent of the narrowing. Treatment options include endoscopic balloon dilation, stent placement, and, in refractory cases, surgical reconstruction (ureteroplasty).

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR)

VUR occurs when urine flows backward from the bladder into the ureters and sometimes the kidneys, increasing the risk of infections and renal scarring.

- Pathophysiology:

This condition is often congenital, arising from an abnormal ureterovesical junction that fails to form an effective one-way valve. - Clinical Manifestations:

Recurrent urinary tract infections, fever, and flank pain are common, particularly in children. Chronic reflux may lead to renal damage if left untreated. - Diagnostic and Therapeutic Strategies:

Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is used to confirm the diagnosis. Management ranges from prophylactic antibiotics to surgical reimplantation of the ureters in severe cases.

Ureteropelvic Junction (UPJ) Obstruction

UPJ obstruction refers to a blockage at the junction where the ureter meets the renal pelvis, impeding urine flow.

- Causes and Risk Factors:

This condition may be congenital or acquired due to factors such as stones, tumors, or fibrotic scarring from previous infections. - Clinical Features:

Patients may experience intermittent flank pain, particularly after fluid intake, and may present with hematuria and signs of urinary infection. - Evaluation and Management:

Diagnosis is typically confirmed through diuretic renography, ultrasound, or CT scans. Treatment options include endoscopic intervention or pyeloplasty—a surgical procedure to reconstruct the obstructed junction.

Ureteral Tumors

Tumors of the ureter, though rare, can be either benign or malignant. Transitional cell carcinoma is the most common malignant tumor affecting the ureter.

- Clinical Indicators:

Painless hematuria, unexplained flank pain, and urinary obstruction are hallmarks of ureteral tumors. Early detection is critical for improving outcomes. - Diagnostic Techniques:

Advanced imaging modalities such as CT urography and MRI, coupled with ureteroscopy and biopsy, are essential for accurate diagnosis and staging. - Treatment Approaches:

Surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment, with the extent of surgery dependent on tumor size and location. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be indicated for malignant cases.

Ureteral Injuries

Traumatic injuries to the ureter can result from surgical mishaps, external trauma, or radiation therapy. Such injuries may lead to urine leakage, infections, or complete obstruction.

- Clinical Presentation:

Signs include abdominal pain, hematuria, and sometimes symptoms of peritonitis if urine extravasates into the abdominal cavity. - Diagnosis and Management:

Imaging studies, including CT scans and retrograde pyelography, help assess the extent of injury. Treatment may involve ureteral stenting, surgical repair, or nephrostomy in severe cases.

Ureterocele

A ureterocele is a congenital malformation where the distal end of the ureter balloons as it enters the bladder, potentially causing obstruction.

- Symptomatology:

Recurrent urinary tract infections, abdominal discomfort, hematuria, and urinary incontinence are common symptoms. - Diagnostic Evaluation:

Ultrasound, VCUG, and cystoscopy are key tools for confirming the diagnosis. - Therapeutic Options:

Endoscopic incision of the ureterocele is the preferred treatment for mild cases, while more severe forms may require surgical reconstruction to restore proper urine flow.

Diagnostic Modalities for Ureteral Conditions

Timely and precise diagnosis is essential for effective management of ureteral disorders. A variety of diagnostic tools, ranging from clinical assessments to advanced imaging techniques, help clinicians pinpoint the exact nature and extent of the pathology.

Clinical Evaluation and History

The diagnostic process begins with a comprehensive clinical examination. A detailed patient history is crucial to understanding symptoms such as flank pain, hematuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Physical examination may reveal tenderness in the flank or lower abdomen, which can provide important clues regarding ureteral involvement.

Imaging Techniques

Imaging studies are indispensable in visualizing the ureters and identifying abnormalities.

- Ultrasound:

This non-invasive modality uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of the urinary tract. It is particularly effective in detecting hydronephrosis, ureteral stones, and congenital anomalies without exposing patients to radiation. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scans:

Non-contrast CT scans are considered the gold standard for diagnosing ureteral stones due to their high sensitivity and specificity. Contrast-enhanced CT urography provides detailed visualization of the entire urinary tract, making it invaluable for assessing strictures, tumors, and other pathologies. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI offers high-resolution images without ionizing radiation, making it suitable for evaluating soft tissue details and vascular involvement, particularly in complex or congenital conditions. - Intravenous Pyelography (IVP):

Although largely supplanted by CT and MRI, IVP involves the injection of contrast dye followed by serial X-rays to visualize the urinary tract. It can be useful for evaluating ureteral obstructions and anatomical anomalies.

Endoscopic Examinations

Direct visualization of the ureteral lumen provides definitive insights into the nature of the disorder.

- Ureteroscopy:

A minimally invasive procedure, ureteroscopy involves inserting a thin, flexible scope through the urethra and bladder into the ureter. It allows for real-time inspection, biopsy, and therapeutic interventions, such as stone removal or tumor ablation. - Cystoscopy:

Although primarily focused on the bladder, cystoscopy can help assess the distal ureter and the ureterovesical junction, especially when evaluating ureteroceles or reflux.

Functional and Nuclear Medicine Tests

Assessing the functional status of the urinary system is critical in conditions like UPJ obstruction.

- Diuretic Renography:

This nuclear medicine test uses a radioactive tracer and diuretics to evaluate renal function and urinary drainage. It is particularly useful for detecting obstructions at the ureteropelvic junction. - Voiding Cystourethrography (VCUG):

VCUG is used to visualize the bladder and urethra during urination, allowing for the diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux and assessment of bladder function.

Tissue Sampling and Laboratory Studies

For suspected tumors or inflammatory conditions, tissue diagnosis is essential.

- Endoscopic Biopsy:

During ureteroscopy, small tissue samples can be obtained for histological examination. This aids in diagnosing malignancies or specific inflammatory diseases. - Fine-Needle Aspiration (FNA):

Guided by imaging, FNA can extract cells from a ureteral mass for cytological evaluation. - Urinalysis and Urine Culture:

Routine urine tests help detect infections, hematuria, and crystalluria, providing essential clues about the underlying disorder. - Blood Tests:

Assessments of serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and electrolytes offer insights into overall renal function and the systemic impact of ureteral obstructions.

Management and Therapeutic Approaches

Effective management of ureteral disorders requires a personalized approach that balances conservative measures with interventional procedures. This section explores the range of therapeutic options available to restore and maintain ureteral function.

Medical Management

Non-surgical interventions are often the first line of treatment.

- Medications:

For ureteral stones, pain relief is achieved through nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and, if necessary, opioids. Alpha-blockers like tamsulosin are prescribed to relax the smooth muscles of the ureter, facilitating stone passage. - Antibiotics:

In the presence of urinary tract infections or pyelonephritis, targeted antibiotic therapy is essential. The choice of antibiotic is guided by culture results and sensitivity patterns, with common options including ciprofloxacin, amoxicillin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Endoscopic Interventions

Minimally invasive techniques have revolutionized the treatment of ureteral conditions.

- Ureteroscopy with Laser Lithotripsy:

This procedure involves inserting a ureteroscope to visualize and fragment stones using laser energy. It can also be employed to biopsy or ablate small tumors. - Balloon Dilation:

For ureteral strictures, endoscopic balloon dilation is performed to widen the narrowed segment. This is frequently followed by the placement of a ureteral stent to maintain patency during the healing process.

Percutaneous and Open Surgical Procedures

When endoscopic methods are insufficient, more invasive surgical techniques may be required.

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL):

For large or complex stones, PCNL involves creating a small incision in the back to access and remove the stone under direct vision. - Ureteral Reimplantation:

This surgical procedure is indicated for severe vesicoureteral reflux or complex strictures. The diseased segment is excised, and the remaining healthy ureter is reattached to the bladder at a new angle to prevent reflux. - Pyeloplasty:

In cases of UPJ obstruction, pyeloplasty involves the surgical reconstruction of the junction between the renal pelvis and ureter, thereby restoring unobstructed urine flow.

Advanced and Innovative Treatments

Recent advances have introduced novel approaches for managing ureteral disorders.

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL):

ESWL employs shock waves generated outside the body to fragment ureteral stones, allowing them to pass naturally. - Laser Therapy:

In addition to lithotripsy, laser ablation techniques are used to treat small tumors and remove obstructive lesions with minimal collateral damage. - Ureteral Stenting:

Temporary stents can be inserted to maintain ureteral patency after procedures or to bypass obstructions, ensuring continuous urine flow during the recovery period. - Robotic-Assisted Surgery:

For complex reconstructions, robotic-assisted laparoscopic techniques offer precision, reduced recovery times, and minimized postoperative pain.

Conservative Management Strategies

In some cases, lifestyle modifications and careful monitoring can manage ureteral conditions effectively.

- Hydration and Dietary Changes:

Adequate fluid intake is fundamental in preventing stone formation. Dietary modifications—such as reducing sodium, animal protein, and oxalate-rich foods—can also lower the risk of recurrent stones. - Regular Follow-Up:

Monitoring through periodic imaging and clinical evaluation ensures early detection of any recurrent or progressive issues.

Nutritional and Supplement Strategies for Ureteral Wellness

Beyond conventional treatments, nutritional supplements can offer additional support for ureteral health. These agents work synergistically to prevent stone formation, reduce inflammation, and maintain the overall integrity of the urinary tract.

Key Supplements and Their Benefits

- Magnesium:

Magnesium plays a critical role in inhibiting the crystallization of calcium oxalate, the most common component of ureteral stones. By binding to oxalate, magnesium reduces its concentration in urine and lowers the risk of stone formation. - Citrate (Potassium Citrate):

Citrate acts as a natural inhibitor of stone formation by binding with calcium in the urine, increasing its solubility, and preventing crystal aggregation. Supplementation can be particularly beneficial for individuals prone to recurrent stones. - Vitamin B6 (Pyridoxine):

Vitamin B6 helps reduce urinary oxalate levels by modulating its metabolic pathways. Lower oxalate levels contribute to a decreased risk of calcium oxalate stone formation. - Cranberry Extract:

Known for its urinary tract protective properties, cranberry extract prevents bacteria from adhering to the urothelium, thereby reducing the incidence of urinary tract infections—a common precursor to ureteral complications. - Probiotics:

Probiotic supplements containing strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium promote a healthy balance of intestinal and urinary microbiota. A balanced microbiome can lower the risk of infections and support overall urinary health. - D-Mannose:

D-Mannose is a naturally occurring sugar that prevents uropathogenic bacteria, particularly E. coli, from binding to the urinary tract lining. Its use is associated with a reduced frequency of urinary tract infections. - Horsetail Extract:

Rich in antioxidants and diuretic compounds, horsetail extract can help increase urine output, thereby flushing out small stones and debris from the urinary tract. - Uva Ursi (Bearberry):

Uva ursi possesses antimicrobial properties and mild diuretic effects, making it effective in treating and preventing urinary tract infections. - N-Acetylcysteine (NAC):

NAC serves as a potent antioxidant that reduces oxidative stress and inflammation in the urinary tract. Its mucolytic properties may also help in maintaining a clear urinary passage.

Integrating Supplements into a Wellness Plan

When considering supplements, it is important to adopt an individualized approach. Consultation with a healthcare provider is recommended to tailor a supplement regimen that complements dietary habits and addresses specific risk factors. Combined with a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains, these supplements can serve as a valuable adjunct in promoting long-term ureteral and urinary tract health.

Best Practices for Ureter and Urinary Health

Maintaining ureteral and overall urinary health requires a holistic approach that includes lifestyle modifications, dietary adjustments, and routine medical care. The following best practices can help reduce the risk of ureteral disorders and support long-term well-being.

Daily Lifestyle Recommendations

- Stay Hydrated:

Drinking ample water throughout the day ensures adequate urine production. This flushes out toxins and reduces the risk of stone formation. - Adopt a Balanced Diet:

A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, while low in sodium, animal protein, and oxalate-rich foods, supports optimal urinary health. - Regular Physical Activity:

Consistent exercise promotes overall well-being and can help maintain healthy kidney function and urine flow. - Avoid Smoking:

Smoking is linked to an increased risk of urinary tract cancers and other urological conditions. Quitting smoking is one of the most effective steps toward improved urinary health. - Limit Caffeine and Alcohol:

These substances can lead to dehydration and irritate the urinary tract. Moderation is key to preventing adverse effects.

Medical and Preventive Measures

- Regular Check-Ups:

Routine visits to a healthcare provider allow for early detection of potential issues. Regular imaging and laboratory tests can monitor urinary tract health effectively. - Medication Management:

Be aware of medications, including certain diuretics and calcium supplements, that may impact urinary function. Use them only under medical supervision. - Hygiene Practices:

Maintaining good genital hygiene is essential in preventing infections that could ascend to the ureters. - Chronic Condition Management:

Conditions such as diabetes and hypertension can affect kidney and urinary tract health. Managing these conditions through lifestyle and medication helps mitigate their impact. - Stress Reduction:

Chronic stress may influence overall health, including urinary function. Techniques such as mindfulness, exercise, and proper sleep hygiene contribute to improved well-being. - Use of Probiotics:

Incorporating probiotics into your diet can help maintain a healthy urinary and gut microbiome, reducing the risk of infections.

Authoritative References and Resources

For those seeking additional information on ureteral and urinary health, a wealth of authoritative resources is available. These references provide in-depth insights, evidence-based guidelines, and the latest research findings.

Recommended Books

- “Clinical Manual of Urology” by Philip M. Hanno, Alan J. Wein, and Alan W. Partin:

This manual offers comprehensive coverage of urological disorders, including detailed discussions on ureteral conditions and their management. - “Campbell-Walsh Urology” by Alan J. Wein, Louis R. Kavoussi, and Andrew C. Novick:

Recognized as a definitive resource, this textbook covers the full spectrum of urology, with extensive sections on the anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the ureters. - “Smith’s Textbook of Endourology” by Arthur D. Smith, Glenn M. Preminger, and Louis R. Kavoussi:

Focused on minimally invasive techniques, this book provides valuable insights into endoscopic procedures and novel treatments for ureteral disorders.

Peer-Reviewed Journals

- The Journal of Urology:

Published by the American Urological Association, this journal features original research, clinical studies, and reviews on a broad range of urological topics, including ureteral pathologies. - European Urology:

This peer-reviewed journal offers cutting-edge research on diagnostic methods, treatment innovations, and outcomes in urological care.

Mobile Applications and Online Tools

- Medscape:

An extensive clinical resource, Medscape provides up-to-date information, guidelines, and drug references relevant to urological practice. - MDCalc:

This app features clinical calculators and decision support tools that aid in the assessment and management of urinary tract conditions. - UpToDate:

A trusted clinical resource, UpToDate offers evidence-based articles and treatment recommendations for a variety of urological disorders, including those affecting the ureters.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary functions of the ureters?

The ureters transport urine from the kidneys to the bladder using peristaltic contractions. They also prevent backflow through an oblique insertion into the bladder and help maintain urine sterility, ensuring the kidneys remain protected from infections.

How are ureteral stones diagnosed?

Ureteral stones are primarily diagnosed using non-contrast CT scans, which provide detailed images of the urinary tract. Ultrasound and X-rays may also be used, especially in sensitive populations, to confirm the presence of calculi.

What treatment options exist for ureteral strictures?

Treatment for ureteral strictures includes endoscopic balloon dilation, stent placement, and, in severe cases, surgical reconstruction. The choice depends on the stricture’s severity, location, and underlying cause.

Can lifestyle changes help prevent ureteral disorders?

Yes, lifestyle modifications such as staying well-hydrated, following a balanced diet, exercising regularly, and avoiding smoking can significantly reduce the risk of ureteral stones and other urinary tract disorders.

How do supplements contribute to ureteral health?

Supplements such as magnesium, citrate, vitamin B6, and cranberry extract can help prevent stone formation and infections by regulating urine composition, reducing crystallization, and maintaining a healthy urinary tract environment.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is intended for educational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare professional for diagnosis, treatment, and answers to your personal health questions.

Please share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social platform to help spread awareness about ureteral and urinary health.