The urinary bladder is a remarkable hollow muscular organ responsible for storing and expelling urine, playing a vital role in waste elimination and fluid balance. Its intricate design, featuring multiple layers and specialized regions, allows it to expand and contract efficiently, safeguarding against infections and ensuring proper continence. This guide provides a deep dive into bladder anatomy, explores its dynamic physiological functions, and discusses common disorders. It also covers advanced diagnostic techniques, modern treatment options, and lifestyle strategies—including nutritional supplements—to maintain optimal bladder health. Whether you are a medical professional or simply curious about your body, this resource is designed to inform and empower your understanding of bladder care.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Insights

- Functional Mechanisms

- Bladder Pathologies

- Diagnostic Strategies

- Treatment Interventions

- Nutritional Support

- Lifestyle and Preventive Tips

- Reliable Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

Anatomical Insights

The urinary bladder’s structure is both complex and fascinating, designed to meet the demands of continuous urine storage and subsequent expulsion. Its design involves distinct regions, specialized layers, and a network of blood vessels, nerves, and supportive tissues—all of which collaborate to maintain its function.

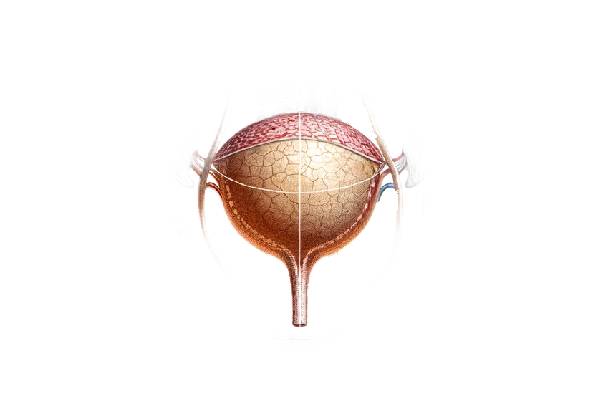

Gross Anatomy and Regional Organization

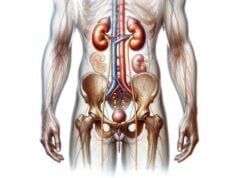

- Location and Position:

The bladder resides in the pelvic cavity. In men, it is situated anterior to the rectum and inferior to the pubic symphysis, lying above the prostate gland. In women, it is positioned anterior to the uterus and vagina. Its pelvic location is secured by several ligaments and connective tissue structures, ensuring stability despite changes in volume. - Shape and Capacity:

When empty, the bladder appears as a compressed, tetrahedral structure. As urine accumulates, it expands into a more spherical form, with a typical capacity ranging from 400 to 600 milliliters. This remarkable elasticity is essential for its role in storage. - Key Regions:

The bladder is divided into several anatomical regions: - Apex: The anterior tip pointing toward the abdominal wall.

- Body: The central, largest portion that expands with urine.

- Fundus (Base): The posterior region, adjacent to the ureters’ entry points.

- Neck: The constricted area that funnels urine into the urethra.

- Trigone: A smooth, triangular region defined by the two ureteral orifices and the internal urethral orifice, crucial for directing urine flow and maintaining continence.

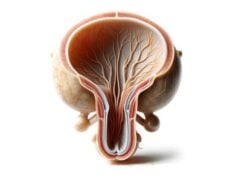

Histological Layers of the Bladder Wall

The bladder wall is composed of several layers, each contributing to its functional integrity:

- Mucosa (Urothelium):

The innermost lining is a specialized transitional epithelium that can stretch extensively as the bladder fills. Beneath the urothelium lies the lamina propria, a connective tissue layer rich in blood vessels and nerve fibers that supports the epithelium. - Submucosa:

This thin layer of connective tissue provides additional support and serves as a conduit for nerves and microvasculature. - Muscularis Propria (Detrusor Muscle):

The detrusor muscle is critical for bladder contraction. It is organized into three layers—an inner longitudinal, a middle circular, and an outer longitudinal layer. Coordinated contraction of the detrusor expels urine during micturition. - Adventitia/Serosa:

The outermost layer comprises loose connective tissue (adventitia) that anchors the bladder to surrounding pelvic structures. The superior surface of the bladder is often covered by a serous membrane (serosa), which is continuous with the peritoneum.

Vascular and Neural Support

- Blood Supply:

The bladder receives arterial blood from several sources: - Superior Vesical Arteries: Branches of the internal iliac arteries supply the bladder’s upper regions.

- Inferior Vesical Arteries: These supply the lower parts, ensuring robust perfusion.

- In women, the Vaginal Arteries also contribute. Venous drainage follows a similar pattern, with blood returning through the vesical venous plexus to the internal iliac veins.

- Nerve Supply:

Bladder function is intricately regulated by the autonomic and somatic nervous systems: - Parasympathetic Fibers: Originating from the pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-S4), they stimulate detrusor contraction to facilitate urination.

- Sympathetic Fibers: Carried by the hypogastric nerves (T11-L2), these promote urine storage by contracting the internal urethral sphincter.

- Somatic Innervation: The pudendal nerve provides voluntary control over the external urethral sphincter, essential for continence.

Lymphatic Drainage and Gender Variations

- Lymph Drainage:

Lymph from the bladder drains to the external, internal, and sacral lymph nodes, playing a crucial role in immune defense and in the staging of bladder cancers. - Gender Differences:

- Male Bladder: Positioned above the prostate, its neck and prostatic urethra are influenced by prostatic tissue, which can affect urinary flow.

- Female Bladder: Located in a more mobile pelvic environment, it is supported by the pubovesical ligaments, and its relatively shorter urethra increases the risk of urinary tract infections.

Supporting Structures

- Ligaments and Muscles:

The bladder is stabilized by supportive ligaments—pubovesical ligaments in women and puboprostatic ligaments in men. Additionally, pelvic floor muscles (such as the levator ani) provide critical support, maintaining bladder position and contributing to urinary continence.

Functional Mechanisms

The urinary bladder is not merely a passive storage container; it is a dynamic organ with critical roles in urine storage, controlled expulsion, and protection of the urinary tract. Its functions are intricately regulated by neural and muscular components that ensure efficiency and reliability.

Urine Storage

- Compliance and Elasticity:

The bladder’s capacity to store urine relies on its compliance—the ability to stretch without a significant rise in internal pressure. This property is conferred by the elasticity of the detrusor muscle and the urothelium. - Sensory Feedback:

Stretch receptors embedded in the bladder wall continuously monitor its filling state. These receptors relay signals to the central nervous system, creating the sensation of bladder fullness and triggering the micturition reflex when a threshold is reached.

Micturition (Urination) Process

Micturition is a carefully coordinated process involving several steps:

- Initiation of Voiding:

As the bladder fills, the increasing stretch of its walls sends afferent signals via the pelvic nerves to the brain. When the bladder reaches a critical volume, the brain triggers the micturition reflex. - Detrusor Contraction and Sphincter Relaxation:

The parasympathetic nervous system stimulates the detrusor muscle to contract forcefully, while the internal urethral sphincter relaxes. Simultaneously, voluntary relaxation of the external urethral sphincter (via the pudendal nerve) allows urine to flow out. - Coordination and Control:

The entire process is modulated by higher brain centers, enabling individuals to control the timing of urination, a crucial aspect of social and personal well-being.

Protective and Continence Mechanisms

- Sphincteric Control:

The internal and external urethral sphincters work in tandem to maintain continence. The internal sphincter, under involuntary control, keeps urine in the bladder during the storage phase, while the external sphincter provides additional voluntary control. - Mucosal Barrier and Immune Function:

The urothelium serves as a barrier to pathogens, while the continuous flushing action of urine minimizes the risk of bacterial colonization. Inflammatory cells within the bladder mucosa offer an additional layer of immune defense.

Interaction with the Reproductive System

In males, the bladder also plays an indirect role in reproductive function:

- Proximity to the Prostate:

The bladder neck’s relationship with the prostate influences the flow of both urine and semen. During ejaculation, the internal urethral sphincter contracts to prevent the retrograde flow of semen into the bladder, ensuring that semen is expelled through the penile urethra.

Bladder Pathologies

A range of conditions can affect the urinary bladder, leading to symptoms that significantly impact quality of life. Understanding these pathologies is key to early diagnosis and effective management.

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

UTIs are among the most prevalent bladder disorders, particularly affecting women.

- Etiology and Risk Factors:

UTIs are primarily caused by bacteria such as Escherichia coli. Risk factors include poor hygiene, sexual activity, and the use of urinary catheters. - Symptoms:

Common symptoms include burning during urination, frequent and urgent need to urinate, cloudy or foul-smelling urine, and lower abdominal pain. In severe cases, hematuria (blood in the urine) may be present. - Treatment and Prevention:

UTIs are usually managed with antibiotics. Preventive strategies include adequate hydration, proper hygiene, and, in recurrent cases, prophylactic antibiotics.

Bladder Stones

Bladder stones form when minerals in urine crystallize and aggregate.

- Causes:

They may develop due to incomplete bladder emptying, chronic UTIs, or urinary tract obstructions. Conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in men can predispose to stone formation. - Clinical Presentation:

Symptoms include lower abdominal pain, painful urination, frequent urination, and hematuria. - Management Options:

Small stones may pass spontaneously, whereas larger stones often require interventions such as cystolitholapaxy (endoscopic fragmentation and removal) or, in severe cases, open surgery.

Interstitial Cystitis (Bladder Pain Syndrome)

Interstitial cystitis (IC) is a chronic condition marked by bladder pain, pressure, and frequent urination.

- Pathophysiology:

Although its exact cause remains unclear, IC is thought to involve defects in the bladder lining, an autoimmune component, and neurogenic inflammation. - Symptoms:

Patients report persistent pelvic pain, a strong urgency to urinate, and discomfort during sexual intercourse. The severity and frequency of symptoms can vary widely. - Treatment Modalities:

IC is managed with a combination of lifestyle changes, bladder instillations, oral medications, pelvic floor physical therapy, and dietary modifications. In refractory cases, surgical intervention may be considered.

Bladder Cancer

Bladder cancer typically originates in the urothelial cells lining the bladder.

- Risk Factors:

Smoking, exposure to industrial chemicals, and chronic bladder irritation are well-known risk factors. - Clinical Signs:

Early signs include painless hematuria. As the disease progresses, patients may experience frequent urination, dysuria, and pelvic pain. - Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies:

Diagnosis involves cystoscopy, biopsy, and imaging studies (CT, MRI). Treatment options range from transurethral resection (TURBT) for non-muscle invasive cancers to radical cystectomy combined with chemotherapy or radiation for advanced stages.

Overactive Bladder (OAB)

OAB is characterized by an uncontrollable urge to urinate, often leading to incontinence.

- Etiology:

Abnormal bladder muscle contractions or neurological disorders can trigger OAB. Other factors such as infections and bladder irritation may also contribute. - Symptomatology:

Symptoms include urgency, frequency, and nocturia (waking at night to urinate). - Management:

Treatment involves lifestyle modifications, pelvic floor muscle exercises, medications (anticholinergics, beta-3 agonists), and, in refractory cases, neuromodulation therapy or intravesical Botox injections.

Bladder Prolapse (Cystocele)

Bladder prolapse, or cystocele, occurs when the bladder descends into the vaginal canal due to weakened pelvic floor muscles.

- Etiology:

Childbirth, aging, and chronic straining are common causes. - Clinical Features:

Symptoms include a feeling of pressure or fullness in the pelvis, urinary incontinence, and discomfort during intercourse. - Treatment Options:

Conservative management involves pelvic floor exercises and pessaries. Severe cases may require surgical repair to restore proper anatomical support.

Neurogenic Bladder

Neurogenic bladder results from nerve damage that disrupts normal bladder control.

- Causes:

Spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and other neurological conditions can impair the neural pathways that regulate bladder function. - Presentation:

Depending on whether the bladder is overactive or underactive, symptoms may range from urinary incontinence to urinary retention, often accompanied by frequent infections. - Therapeutic Approaches:

Management strategies include medications, intermittent catheterization, bladder training, and sometimes surgical interventions such as bladder augmentation.

Diagnostic Strategies

Effective diagnosis of bladder disorders is paramount for determining the appropriate treatment plan. A combination of clinical assessments, laboratory tests, imaging, and specialized procedures is used to evaluate bladder health.

Clinical Assessment and History

- Patient History:

A detailed medical history helps identify symptoms such as dysuria, hematuria, urgency, frequency, and pelvic pain. Information about previous urinary issues and lifestyle factors is also critical. - Physical Examination:

For men, a digital rectal exam assesses prostate influence on bladder function. For women, a pelvic examination can reveal signs of prolapse or other anatomical abnormalities.

Laboratory Investigations

- Urinalysis:

This fundamental test analyzes urine for the presence of blood, white blood cells, bacteria, and crystals, which can indicate infections, stones, or other abnormalities. - Urine Culture and Sensitivity:

Culturing urine identifies pathogenic bacteria and helps determine the most effective antibiotic treatment. - Urine Cytology:

Evaluating urine for abnormal cells is a key step in screening for bladder cancer, especially in patients with hematuria.

Imaging Modalities

- Ultrasound:

Non-invasive and radiation-free, ultrasound is commonly used to visualize the bladder’s shape, wall thickness, and to detect stones, tumors, or signs of urinary retention. - X-rays and Intravenous Pyelography (IVP):

IVP uses contrast dye to outline the urinary tract, providing detailed images that reveal structural abnormalities. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scans:

CT scans offer high-resolution cross-sectional images that are invaluable in detecting tumors, stones, and other complex structural issues. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI provides superior soft tissue contrast and is particularly useful for staging bladder cancer and assessing congenital anomalies.

Endoscopic Evaluations

- Cystoscopy:

A cystoscope is inserted through the urethra to directly visualize the interior bladder lining. This procedure is crucial for diagnosing tumors, stones, and interstitial cystitis, and allows for biopsies. - Ureteroscopy:

Occasionally, ureteroscopy is employed to evaluate the ureteral orifices and assess the upper parts of the bladder where ureteral inputs occur.

Urodynamic Testing

- Uroflowmetry:

This test measures the flow rate and volume of urine, helping to identify obstructions or dysfunctional voiding patterns. - Cystometry and Pressure-Flow Studies:

These tests evaluate the bladder’s pressure during filling and emptying, providing insights into detrusor function and bladder compliance.

Histopathological Analysis

- Bladder Biopsy:

Tissue samples obtained during cystoscopy are examined microscopically to diagnose cancers, chronic inflammation, and other pathological conditions. - Histopathology:

Detailed analysis of biopsy samples confirms the cellular characteristics of lesions and guides treatment decisions.

Advanced Techniques

- Fluoroscopy:

Real-time X-ray imaging during contrast studies aids in dynamic assessments of bladder function. - Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scans:

PET scans evaluate metabolic activity in bladder tissues, particularly useful in identifying malignant lesions and metastases.

Treatment Interventions

The management of bladder disorders is tailored to the specific condition, symptom severity, and overall health of the patient. Treatment options range from conservative measures and medication to minimally invasive procedures and advanced surgical techniques.

Medical Management

- Antibiotic Therapy:

UTIs are primarily managed with antibiotics such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, or nitrofurantoin. Treatment duration and antibiotic choice are guided by urine culture and sensitivity results. - Anticholinergics and Beta-3 Agonists:

Overactive bladder is managed with medications like oxybutynin, tolterodine, and mirabegron, which relax the detrusor muscle and increase bladder capacity. - Analgesics and Anti-inflammatory Agents:

For conditions such as interstitial cystitis, medications like phenazopyridine and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) offer symptomatic relief. - Hormonal Therapy:

Topical estrogen can be effective in postmenopausal women with bladder atrophy and prolapse, improving tissue health and reducing infection risk.

Minimally Invasive Procedures

- Bladder Instillations:

Direct instillation of therapeutic agents (e.g., dimethyl sulfoxide, heparin, lidocaine) into the bladder can reduce inflammation and relieve symptoms of interstitial cystitis. - Intravesical Botox Injections:

Botox injections help control overactive bladder symptoms by reducing involuntary detrusor contractions. - Cystolitholapaxy:

This endoscopic procedure uses a cystoscope to fragment and remove bladder stones without the need for open surgery. - Urethral Dilation and Urethrotomy:

These procedures address urethral strictures by widening the urethral lumen through gradual dilation or endoscopic incision.

Surgical Interventions

- Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumor (TURBT):

TURBT is the standard treatment for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, involving endoscopic removal of tumors from the bladder wall. - Cystectomy:

In cases of muscle-invasive bladder cancer, partial or radical cystectomy may be necessary. Urinary diversion procedures, such as the creation of an ileal conduit or neobladder, are then performed. - Bladder Augmentation:

For patients with a small or poorly compliant bladder, augmentation using a segment of intestine increases capacity and reduces intravesical pressure. - Sling Procedures and Artificial Urinary Sphincter:

These surgeries help manage stress urinary incontinence by supporting the urethra or providing mechanical control over urine flow. - Sacral Neuromodulation:

Implantation of a device to stimulate sacral nerves can improve bladder control in patients with refractory overactive bladder or neurogenic bladder.

Advanced and Innovative Approaches

- Stem Cell Therapy and Tissue Engineering:

Experimental techniques involving stem cells and bioengineered scaffolds show promise in regenerating damaged bladder tissue, particularly in neurogenic or radiation-induced bladder dysfunction. - Robotic-Assisted Surgery:

Robotic platforms enable precise and minimally invasive bladder surgeries, reducing recovery times and postoperative complications.

Conservative and Behavioral Therapies

- Bladder Training and Timed Voiding:

Establishing regular voiding schedules can enhance bladder capacity and reduce symptoms of urgency and incontinence. - Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation:

Kegel exercises strengthen the pelvic floor muscles, improving bladder support and enhancing continence. - Dietary Modifications:

Avoiding bladder irritants such as caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods can reduce symptoms in patients with overactive bladder and interstitial cystitis.

Nutritional Support

Certain nutritional supplements can enhance bladder health and support the urinary system. When combined with a balanced diet, these supplements help maintain the bladder’s environment, prevent infections, and reduce inflammation.

Key Supplements

- Cranberry Extract:

Rich in proanthocyanidins, cranberry extract helps prevent bacterial adhesion—especially of E. coli—thereby lowering the risk of urinary tract infections. - D-Mannose:

This naturally occurring sugar binds to bacterial cells, preventing them from adhering to the bladder lining and reducing infection recurrence. - Probiotics:

Beneficial bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains, support a balanced microbiome in the urinary tract, reducing infection risk. - Vitamin C:

As an antioxidant, vitamin C helps acidify urine and strengthen the immune system, making the bladder environment less conducive to bacterial growth. - Magnesium:

Magnesium aids in proper muscle and nerve function, which is critical for maintaining the tone of the bladder and urethral sphincters. - Horsetail Extract:

With diuretic and antioxidant properties, horsetail extract supports urinary tract health by increasing urine output and flushing out toxins. - Saw Palmetto and Pumpkin Seed Extract:

Often used to manage benign prostatic hyperplasia in men, these supplements also improve urine flow and reduce inflammation in the lower urinary tract. - N-acetylcysteine (NAC):

NAC acts as a powerful antioxidant that reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, promoting overall bladder health.

Integrating Supplements

It is important to consult with a healthcare provider before starting any supplement regimen. When incorporated into a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, these supplements can serve as an adjunct in promoting long-term bladder health.

Lifestyle and Preventive Tips

A proactive approach to bladder health involves adopting lifestyle practices that minimize risk factors and promote overall urinary well-being.

Daily Practices

- Hydration:

Drinking plenty of water ensures that urine is continuously flushed out, reducing the risk of infection and stone formation. - Good Hygiene:

Regular and proper genital hygiene helps prevent the introduction of pathogens into the urinary tract. - Regular Voiding:

Avoid holding urine for long periods to prevent bladder overdistension and reduce the risk of infections. - Comfortable Clothing:

Wearing loose, breathable clothing reduces moisture and friction, which can irritate the bladder. - Avoid Bladder Irritants:

Limit exposure to irritants such as caffeine, alcohol, and highly spiced foods, which may exacerbate bladder symptoms.

Pelvic Health

- Pelvic Floor Exercises:

Regularly performing Kegel exercises can strengthen the muscles that support the bladder and urethra, helping to prevent incontinence. - Weight Management:

Maintaining a healthy weight reduces pressure on the bladder and pelvic floor muscles. - Stress Reduction:

Techniques such as yoga, meditation, and regular physical activity can help manage stress, which may influence bladder function.

Regular Medical Monitoring

- Routine Check-Ups:

Regular visits to a healthcare provider allow for early detection and treatment of bladder issues. - Screening:

For individuals at risk, regular urine tests and imaging studies can help identify problems before they become severe. - Management of Chronic Conditions:

Effectively managing conditions like diabetes and hypertension is critical, as these can predispose individuals to urinary tract complications.

Reliable Resources

Staying informed with accurate, up-to-date information is essential for both patients and healthcare professionals. The following resources provide a wealth of knowledge about urinary bladder anatomy, physiology, and treatment strategies.

Books

- “Smith’s General Urology” by Emil A. Tanagho and Jack W. McAninch

A comprehensive text that covers all aspects of urology, including detailed sections on bladder diseases and their management. - “Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology” by Alan J. Wein, Louis R. Kavoussi, and Andrew C. Novick

A definitive guide in urology offering in-depth information on bladder anatomy, pathology, and treatment options. - “The Urology Textbook” by Hohenfellner, Michael, and Simon Horenblas

This textbook provides an extensive overview of urological disorders, emphasizing diagnostic and therapeutic techniques related to the bladder.

Academic Journals

- The Journal of Urology

A peer-reviewed journal published by the American Urological Association, featuring the latest research, reviews, and clinical studies on bladder and urinary tract health. - Urology

A reputable journal that focuses on innovative diagnostic methods, treatment approaches, and research findings in the field of urology.

Mobile Apps and Online Tools

- Urology Times

An app that delivers up-to-date news, clinical guidelines, and research updates in urology, keeping professionals informed about bladder health. - My Urology App

Designed for patients, this app offers educational resources, symptom tracking, and management tips for various bladder conditions. - Bladder Pal

A mobile application that helps individuals monitor their bladder health, manage symptoms, and access useful information on treatment options.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary functions of the urinary bladder?

The urinary bladder stores urine produced by the kidneys and expels it during micturition. It maintains continence through coordinated sphincter action and, in the case of women, supports pelvic organ function.

How are urinary tract infections diagnosed?

UTIs are diagnosed using urinalysis, urine culture, and sometimes urine cytology. Imaging studies may be employed if structural abnormalities are suspected.

What treatment options exist for overactive bladder?

Overactive bladder is managed with lifestyle modifications, pelvic floor exercises, medications (anticholinergics and beta-3 agonists), and minimally invasive procedures like intravesical Botox injections if needed.

How can lifestyle changes help prevent bladder conditions?

Maintaining proper hydration, practicing good hygiene, voiding regularly, and avoiding irritants like caffeine and alcohol help reduce the risk of UTIs, bladder stones, and overactive bladder symptoms.

What supplements support urinary bladder health?

Supplements such as cranberry extract, D-mannose, probiotics, vitamin C, magnesium, and horsetail extract support bladder health by preventing infections, reducing inflammation, and improving muscle function.

Disclaimer

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and is not intended as a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized recommendations and treatment options.

Please share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred platform to help promote awareness about urinary bladder health and encourage proactive urinary care.