Apathic-akinetic syndrome is characterized by profound reductions in motivation, spontaneous movement, and emotional responsiveness, often accompanied by slowed speech and diminished goal-directed behavior. Commonly arising from frontal-subcortical circuit disruptions—due to stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, or brain injury—it profoundly impacts daily functioning, social engagement, and quality of life. Although its presentation can mimic depression or other motor disorders, distinct clinical features and targeted interventions exist. This comprehensive article explores the syndrome’s defining characteristics, symptom patterns, contributing vulnerabilities, diagnostic strategies, and evidence-based treatments—equipping patients, caregivers, and clinicians with the knowledge to recognize, assess, and manage apathic-akinetic syndrome effectively.

Table of Contents

- A Thorough Examination of Fundamental Characteristics

- Spotlight on Clinical Presentations

- Exploring Predispositions and Preventive Strategies

- Techniques for Evaluation and Diagnosis

- Therapeutic Strategies and Management Approaches

- Key Questions and Brief Answers

A Thorough Examination of Fundamental Characteristics

Apathic-akinetic syndrome (AAS) sits at the intersection of neurology and psychiatry, presenting as a striking combination of apathy (lack of interest or motivation) and akinesia (reduced movement). While the term “apathetic-abulic syndrome” often overlaps, AAS specifically highlights both motivational and motor deficits. First described in mid-20th-century neurology literature, it gained recognition through cases of frontal lobe infarcts, progressive supranuclear palsy, and normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH). In NPH, for instance, the classic Hakim–Adams triad—gait disturbance, urinary incontinence, and cognitive decline—often includes conspicuous abulia, demonstrating how apathic-akinetic features integrate into broader syndromes.

At its core, AAS reflects dysfunction in frontal-subcortical circuits, particularly pathways linking the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and basal ganglia. These loops regulate motivation, initiation of movement, and reward processing. Disruption—through ischemic injury, neurodegeneration (as in Parkinson’s disease or Alzheimer’s), traumatic brain injury, or tumor—impairs dopamine and acetylcholine signaling, leading to flattened affect, slowed responses, and diminished goal pursuit.

Epidemiological insights vary by etiology:

- Stroke-Related AAS: Up to 30% of patients with frontal lobe infarcts develop apathy or abulia within months, often correlating with lesion size and location.

- Parkinsonian Apathy: Approximately 40% of Parkinson’s disease patients exhibit significant apathy, sometimes independent of motor severity.

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Apathy is one of the earliest neuropsychiatric symptoms, affecting 50–70% of individuals, and predicts more rapid cognitive decline.

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus: Akinetic features paired with cognitive and urinary symptoms occur in 10–20% of idiopathic NPH cases.

In clinical practice, AAS may be underrecognized, as patients and families attribute reduced initiative to depression, medication side effects, or “just getting older.” Yet apathy in AAS lacks the pervasive sadness of depression; rather, individuals appear emotionally flat, indifferent to previously enjoyed activities, and display diminished spontaneous movement even when capable. Moreover, unlike the rigidity and tremor of classic parkinsonism, akinesia in AAS focuses on initiation deficits—patients may stand motionless, unable to begin walking or speaking, until prompted.

Understanding these core features illuminates why targeted assessment and management differ from treating mood disorders or primary movement disorders alone. Recognizing AAS as a distinct clinical entity allows for tailored pharmacological and rehabilitative strategies, aiming to restore motivation, boost neurotransmitter function, and re-engage patients in meaningful activities.

Spotlight on Clinical Presentations

Apathic-akinetic syndrome manifests with a recognizable constellation of motivational, motor, and emotional signs that profoundly interfere with daily life. While presentations vary by underlying cause, common clinical features include:

Motivational and Behavioral Signs

- Avolition: Marked reduction in self-initiated activities—patients may sit for hours without engaging in tasks they once enjoyed.

- Abulia: Difficulty initiating actions—akin to “mental paralysis,” requiring external cues to start routine behaviors like dressing or eating.

- Reduced Spontaneity: Sparse spontaneous speech or social interaction; conversations may be limited to brief responses when prompted.

- Diminished Goal Pursuit: Lack of drive to complete projects, follow hobbies, or plan future events.

Motor and Psychomotor Indicators

- Akinesia: Noticeable slowness or absence of movement initiation; patients may remain frozen in posture until physically guided.

- Bradykinesia Overlap: While not classic parkinsonian bradykinesia, initiation deficits result in slow gait or prolonged reaction times.

- Speech Slowing (Hypophonia): Soft, monotone speech lacking spontaneous elaboration; conversation resembles short, one-word replies.

- Facial Masking: Reduced facial expressiveness, often misinterpreted as disinterest or sadness.

Emotional and Affective Clues

- Emotional Blunting: Diminished emotional responses to pleasant or distressing events—patients may show little reaction to news or personal stories.

- Reduced Pleasure (Anhedonia): Impaired ability to experience enjoyment, separate from lack of motivation; activities may feel neutral rather than rewarding.

Cognitive and Executive Patterns

- Impaired Planning and Organization: Difficulty sequencing tasks, managing time, or switching between activities.

- Decreased Attention Span: Struggling to sustain focus on conversations or reading, though comprehension may remain intact.

Differential Patterns

While depression shares low mood and reduced activity, key distinctions help differentiate AAS: individuals with AAS lack pervasive sadness or guilt, and antidepressants often have limited impact on motivation deficits. In contrast to catatonia—a syndrome of motor immobility and stupor—patients with AAS respond to prompts and may engage when externally motivated.

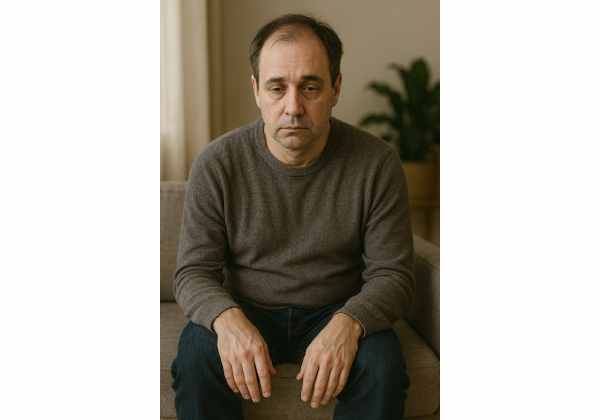

Real-World Illustrations

- A retired engineer who no longer initiates daily walks despite enjoying them before a head injury.

- A Parkinson’s patient who sits by the window, staring blankly, unable to start household chores until physically encouraged.

- An NPH patient who remains motionless on the examination table, requiring repeated instructions to follow simple commands.

Recognizing these clinical presentations—especially when multiple domains converge—allows caregivers and clinicians to move beyond mislabeling apathy as laziness or depression. Early identification of AAS sets the stage for targeted interventions that address both motor initiation and motivational deficits, improving overall engagement and quality of life.

Exploring Predispositions and Preventive Strategies

Understanding who is most susceptible to apathic-akinetic syndrome and how to lower that risk is essential for proactive care. Predisposing factors span neurological, vascular, and lifestyle domains:

Neurological and Medical Risk Factors

- Frontal Lobe Lesions: Strokes, tumors, or trauma affecting prefrontal cortex–basal ganglia circuits disrupt motivation and movement initiation.

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias frequently feature apathy and akinesia.

- Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus (NPH): Ventricular enlargement exerts pressure on periventricular white matter tracts, leading to gait apraxia, urinary symptoms, and abulia.

- Infections and Metabolic Disorders: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, hepatic encephalopathy, and B12 deficiency can impair frontal-subcortical networks.

Vascular and Cardiovascular Contributors

- Small Vessel Disease: Chronic ischemia in deep white matter increases risk for subcortical vascular dementia, often presenting with prominent apathy and psychomotor slowing.

- Hypertension and Diabetes: Poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors exacerbate microvascular damage in brain circuits critical for motivation.

Medications and Toxins

- Antipsychotics and Dopamine Antagonists: Drugs like haloperidol can induce parkinsonian features and akinesia, compounding apathy.

- Sedative Agents: Benzodiazepines or high-dose opioids may cause sedation mistaken for motivational deficits.

- Chronic Alcohol Use: Neurotoxicity from alcohol accelerates frontal lobe damage and cognitive slowing.

Preventive and Protective Measures

While complete prevention of AAS is not always possible, especially when caused by unavoidable injuries, several strategies can mitigate risk and severity:

- Optimizing Vascular Health:

- Blood Pressure and Glucose Control: Adhering to antihypertensive and antidiabetic regimens reduces small vessel damage.

- Cholesterol Management: Statin therapy and dietary modifications support vascular integrity.

- Early Rehabilitation After Brain Injury or Stroke:

- Repetitive Task Training: Engaging patients in goal-oriented activities soon after insult promotes neuroplasticity in frontal circuits.

- Motivation-Focused Therapy: Incorporating reward-based tasks and immediate feedback can counter early apathy.

- Medication Review and Adjustment:

- Minimizing Dopamine-Blocking Agents: When possible, substitute antipsychotics with lower extrapyramidal risks or use lowest effective doses.

- Avoiding Over-Sedation: Regularly assess sedative load to prevent drug-induced akinesia.

- Lifestyle and Cognitive Enrichment:

- Physical Activity: Regular aerobic and resistance exercise enhances dopaminergic tone and supports white matter health.

- Cognitive Engagement: Puzzles, social interaction, and continuing education stimulate frontal networks.

- Healthy Sleep Habits: Adequate restorative sleep aids neurotransmitter balance and motivation.

- Caregiver and Environmental Support:

- Structured Routines: Predictable schedules reduce the cognitive load of initiating tasks.

- Cueing and Prompting: Use of verbal, visual, or tactile cues can help bridge initiation gaps.

- Environmental Modifications: Simplifying living spaces and reducing clutter lowers barriers to activity.

Resilience Analogy

Think of frontal-subcortical circuits as a grooved track guiding a train (behavior and motivation). Vascular damage, neurodegeneration, or toxins add pebbles that derail momentum. Preventive measures—exercise, cognitive engagement, vascular control—act like track maintenance crews, clearing debris and keeping the train running smoothly.

By identifying those at heightened risk and employing these preventive tactics, clinicians and caregivers can delay or reduce the severity of apathic-akinetic syndrome, preserving autonomy and life satisfaction.

Techniques for Evaluation and Diagnosis

Accurate identification of apathic-akinetic syndrome relies on a multi-pronged evaluation that distinguishes its features from other conditions and quantifies severity to guide treatment.

1. Comprehensive Clinical History

- Symptom Chronology: Onset, progression, and fluctuation of motivation and movement deficits.

- Medical Background: History of stroke, trauma, neurodegenerative disease, infections, or metabolic imbalances.

- Medication Review: Identifying agents that may contribute to sedation or akinesia.

2. Neurological and Neuropsychological Examination

- Neurological Exam: Assess gait initiation, tone, reflexes, and cranial nerve function for coexisting motor signs.

- Apathy Scales: Tools like the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) and the Starkstein Apathy Scale provide validated measures of motivational deficits.

- Executive Function Tests: Trail Making Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, and verbal fluency tasks evaluate planning and initiation abilities.

3. Cognitive and Mood Assessment

- Depression Screening: Use of PHQ-9 or Hamilton Depression Rating Scale to differentiate apathy from depressive anhedonia.

- Cognitive Batteries: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) or Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to gauge global cognitive impact.

4. Neuroimaging and Electrophysiology

- MRI/CT Scans: Identify frontal lobe infarcts, hydrocephalus, white matter lesions, or tumors affecting motivation circuits.

- SPECT/PET: Functional imaging to detect hypoperfusion or metabolic deficits in frontal-subcortical pathways.

- EEG: Rule out encephalopathy or seizure disorders presenting with confusion or motor slowing.

5. Laboratory Investigations

- Blood Tests: Thyroid function, vitamin B12, liver and kidney panels to exclude reversible medical causes.

- CSF Analysis: In suspected infections or inflammatory disorders.

6. Differential Diagnosis

- Depression: Distinguished by pervasive sadness, guilt, and negative cognitions, rather than isolated motivational and motor deficits.

- Catatonia: Characterized by waxy flexibility, posturing, and echolalia—features absent in AAS.

- Parkinsonism: Classic resting tremor and rigidity predominate in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, while AAS emphasizes initiation failure.

- Locked-in Syndrome: Severe brainstem lesions cause quadriplegia with preserved consciousness; AAS patients remain mobile if prompted.

7. Functional Impact and Severity Grading

- Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scales: Barthel Index or Functional Independence Measure (FIM) quantify the degree of assistance required.

- Quality-of-Life Questionnaires: Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale or Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire to capture patient-reported outcomes.

Case Illustration

A 68-year-old man with history of NPH presents with slow gait, bladder urgency, and marked apathy. MRI confirms ventricular enlargement; AES score indicates severe apathy, while MMSE remains preserved. Following diagnosis, he undergoes CSF shunting, leading to improved gait and motivation, highlighting the importance of accurate evaluation and timely intervention.

Through these comprehensive techniques, clinicians can confirm apathic-akinetic syndrome, differentiate it from mimics, and tailor treatment plans that address the underlying causes and functional impairments.

Therapeutic Strategies and Management Approaches

Managing apathic-akinetic syndrome requires a personalized, multidisciplinary approach combining pharmacological, rehabilitative, and environmental interventions to restore motivation, improve mobility, and enhance quality of life.

1. Pharmacological Interventions

- Dopaminergic Agents:

- Levodopa/Carbidopa: Especially in Parkinsonian variants, boosting dopamine improves initiation and motivation.

- Dopamine Agonists (e.g., pramipexole): May reduce apathy in some patients, though side effects (impulse control issues) require monitoring.

- Psychostimulants:

- Methylphenidate or Modafinil: Off-label use can enhance energy, attention, and drive by increasing dopaminergic and noradrenergic tone.

- Cholinesterase Inhibitors:

- Rivastigmine or Donepezil: In Alzheimer’s-related apathy, boosting acetylcholine may partially restore motivation circuits.

- Serotonergic Modulators:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Useful when comorbid depression is present, though limited impact on pure apathy.

- Amantadine:

- NMDA receptor antagonist with dopaminergic effects, sometimes improving initiation deficits in TBI or stroke patients.

2. Rehabilitative and Behavioral Therapies

- Goal-Oriented Task Training:

- Breaking activities into small steps with clear, immediate rewards boosts engagement and counters initiation failures.

- Behavioral Activation:

- Scheduling pleasurable or meaningful activities—with caregiver support—to reconnect patients with reinforcing experiences.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy:

- Exercises targeting balance, strength, and gait initiation; environmental adaptations (grab bars, simplified layouts) reduce barriers to movement.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation:

- Executive function drills, planning exercises, and strategy training improve task initiation and sequencing.

3. Neuromodulation Techniques

- Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS):

- Targeting dorsolateral prefrontal cortex may enhance cortical excitability and motivation in treatment-resistant cases.

- Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS):

- In select Parkinsonian patients, subthalamic nucleus or nucleus accumbens stimulation has shown promise for apathy, though outcomes vary.

4. Environmental and Caregiver Strategies

- Structured Routines and Cues:

- Visual schedules, alarms, and prompts help initiate daily activities.

- Positive Reinforcement:

- Verbal praise, token systems, or simple rewards encourage engagement and persistence.

- Caregiver Education:

- Training families to recognize apathy-related behaviors, use prompting techniques, and avoid excessive assistance that undermines agency.

- Supportive Social Engagement:

- Group activities, community programs, and volunteer opportunities provide external motivation and social reinforcement.

5. Integrative Approaches

- Mind-Body Therapies:

- Tai chi, yoga, and dance movement therapy foster gentle activation and connect movement with emotional expression.

- Nutrition and Supplements:

- Omega-3 fatty acids, B-vitamins, and antioxidants may support neuronal health—adjunctive to core treatments.

6. Monitoring and Adjustment

- Regular Outcome Tracking:

- Reassessing apathy scales, motor function tests, and ADL measures every 3–6 months guides medication adjustments and therapy intensity.

- Relapse Prevention Plans:

- Identifying early warning signs—withdrawal, reduced activity—and specifying rapid-response interventions (booster rTMS, medication review).

- Long-Term Support:

- Ongoing engagement with rehabilitation services, support groups, and community resources sustains gains and prevents functional decline.

Recovery Analogy

Treating AAS is like restoring a dimmed lighthouse: pharmacological “bulbs” brighten neurotransmitter pathways, rehabilitative “keepers” polish lenses (motivation skills), and environmental “structures” ensure the light shines consistently—guiding patients safely through daily life’s waves.

By weaving together these therapeutic strands, clinicians can craft comprehensive management plans that not only alleviate apathy and akinesia but also reignite patients’ engagement, meaning, and independence.

Key Questions and Brief Answers

What causes apathic-akinetic syndrome?

Apathic-akinetic syndrome arises from disruptions in frontal-subcortical circuits—due to stroke, neurodegeneration (e.g., Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s), hydrocephalus, or brain injury—impairing dopamine and acetylcholine pathways that drive motivation and movement initiation.

How does AAS differ from depression?

Unlike depression, AAS features flat affect and initiation deficits without pervasive sadness or guilt. Antidepressants may not improve apathy, whereas dopamine-boosting treatments often restore motivation in AAS.

Can apathic-akinetic syndrome be reversed?

Reversibility depends on cause: NPH patients may improve dramatically after shunting; stroke-related cases benefit from early rehabilitation; in neurodegenerative disorders, interventions can reduce severity but not fully reverse progression.

What assessment tools measure apathy?*

Validated scales include the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) and the Starkstein Apathy Scale, which quantify motivational deficits and track treatment response over time.

Are stimulants safe for treating AAS?*

Off-label stimulants like methylphenidate can enhance drive and attention; however, careful monitoring for cardiovascular effects, insomnia, and potential overactivation is essential.

How can caregivers support initiation deficits?

Caregivers can provide structured routines, visual and verbal prompts, positive reinforcement, and simplified task breakdowns—helping patients overcome initiation blocks without fostering dependency.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and does not substitute professional medical advice. If you or a loved one experiences signs of apathic-akinetic syndrome, please consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized evaluation and treatment.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or any platform you prefer—and follow us on social media for more expert insights. Your support helps us continue creating high-quality content!