Keratitis, an inflammation of the cornea—the transparent front part of the eye—can quickly become vision-threatening if not addressed promptly and effectively. It affects individuals of all ages, with causes ranging from infections (bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic) to trauma and immune-related disorders. Early diagnosis and tailored treatment are essential to preserve vision and prevent complications. In this in-depth guide, we’ll explore keratitis from every angle: what it is, how it develops, proven medical and surgical therapies, recent innovations, ongoing research, and actionable steps you can take to protect your eye health.

Table of Contents

- Condition Overview and Epidemiology

- Conventional and Pharmacological Therapies

- Surgical and Interventional Procedures

- Emerging Innovations and Advanced Technologies

- Clinical Trials and Future Directions

- Frequently Asked Questions

Condition Overview and Epidemiology

Keratitis refers to any inflammation of the cornea, the eye’s clear, dome-shaped surface. Because the cornea is vital for focusing vision, inflammation—even if mild—can seriously impact sight.

Types of Keratitis

- Infectious Keratitis:

- Bacterial: Most common, especially in contact lens users.

- Viral: Herpes simplex virus (HSV) and herpes zoster virus (shingles).

- Fungal: Often associated with eye trauma involving plants or soil.

- Parasitic: Acanthamoeba keratitis, frequently linked to improper contact lens care.

- Noninfectious Keratitis:

- Due to trauma, dry eye, exposure, allergies, or autoimmune conditions.

Pathophysiology

- Infections or injury cause the cornea’s protective layer to break down, allowing microorganisms or irritants to invade.

- The immune response leads to swelling, cell death, and sometimes scarring.

Epidemiology and Demographics

- Keratitis affects millions worldwide each year.

- Most common in young and middle-aged adults, but can affect all ages.

- Contact lens wearers have a significantly increased risk.

- Incidence is higher in tropical and developing regions for fungal and parasitic forms.

Risk Factors

- Poor contact lens hygiene or extended wear

- Eye trauma or surgery

- Pre-existing ocular surface disease (dry eye, eyelid disorders)

- Immunosuppression (e.g., HIV, steroids)

- Exposure to contaminated water (swimming with lenses)

Symptoms

- Eye redness, pain, tearing

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Blurred vision or decreased visual acuity

- Foreign body sensation

- Discharge (watery or purulent)

- Sometimes, a visible white spot on the cornea

Diagnosis

- Detailed history and slit-lamp examination by an eye specialist

- Corneal scraping for cultures and sensitivity (in infectious cases)

- PCR or confocal microscopy for atypical pathogens

Practical Advice

- Never ignore red, painful, or blurry eyes—seek prompt evaluation.

- If you wear contact lenses, always practice proper hygiene and never sleep in them unless prescribed.

Conventional and Pharmacological Therapies

The management of keratitis depends on its underlying cause. Early and precise treatment can prevent corneal scarring, ulceration, and even vision loss.

Bacterial Keratitis

- Antibiotic Eye Drops:

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics (e.g., fluoroquinolones) started empirically.

- Tailor therapy based on culture results when available.

- Fortified Antibiotic Drops:

- Higher-concentration preparations (e.g., vancomycin, tobramycin) for severe cases.

- Cycloplegics:

- Drops to relax the eye, reduce pain, and prevent synechiae (iris sticking to lens).

Viral Keratitis

- Herpes Simplex Keratitis:

- Topical or oral antivirals (acyclovir, ganciclovir).

- Topical steroids (with careful supervision) in stromal or immune-mediated cases.

- Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus:

- Prompt oral antivirals (within 72 hours) and lubricating drops.

- Steroids if there is significant inflammation.

Fungal Keratitis

- Antifungal Drops:

- Natamycin, amphotericin B, voriconazole, depending on pathogen.

- Treatment is typically prolonged—often several weeks.

- Adjunct Oral Therapy:

- In severe or deep infections, systemic antifungals may be added.

Acanthamoeba Keratitis

- Anti-amoebic Therapy:

- Combination of biguanides (polyhexamethylene biguanide) and diamidines (propamidine).

- Treatment can be lengthy and challenging.

Noninfectious Keratitis

- Artificial Tears:

- Frequent lubrication for dry eye–related keratitis.

- Topical Steroids or Immunomodulators:

- For inflammation due to autoimmune conditions (use under close medical supervision).

- Treat Underlying Cause:

- Correct eyelid abnormalities, manage allergies, or discontinue harmful medications.

General Principles

- Pain Management:

- Oral analgesics or cold compresses.

- Monitor Response:

- Daily follow-up for severe or infectious cases.

Preventive Measures

- Strict contact lens hygiene

- Protective eyewear for activities with risk of eye injury

- Prompt treatment of underlying systemic diseases

Practical Tips

- Never use steroid drops unless prescribed by an ophthalmologist—they can worsen infections.

- Complete the full course of treatment, even if symptoms improve.

- Keep eyes shielded from dust, smoke, and irritants during healing.

Surgical and Interventional Procedures

While most cases of keratitis can be treated medically, surgery may be needed if the infection or inflammation is severe or unresponsive to therapy.

Key Surgical and Interventional Approaches

- Corneal Debridement

- Mechanical removal of infected or necrotic tissue to enhance drug penetration.

- Performed under topical anesthesia at the slit lamp or in an operating room.

- Therapeutic Penetrating Keratoplasty (PKP)

- Emergency corneal transplant to remove infected or scarred tissue.

- Indicated for non-healing ulcers, perforation, or severe thinning.

- Lamellar Keratoplasty

- Partial-thickness transplant, sparing healthy corneal tissue.

- Used in selected cases with localized disease.

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation

- Placement of a biological membrane to promote healing, reduce inflammation, and minimize scarring.

- Tissue Adhesives and Patch Grafts

- Cyanoacrylate glue or other biological adhesives for small perforations.

- Temporary or permanent patch grafts as a bridge to transplantation.

- Intrastromal or Intracameral Injections

- Direct delivery of antifungals, antibiotics, or antivirals for deep or recalcitrant infections.

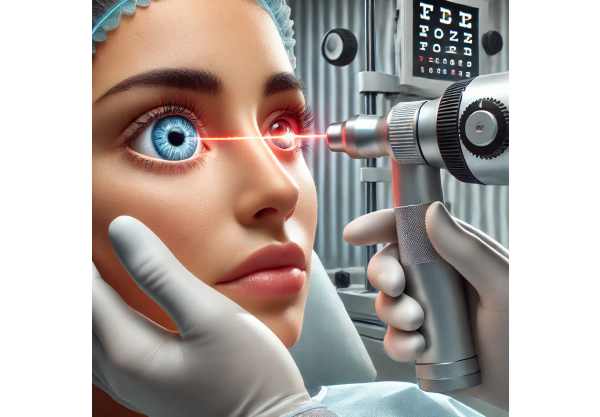

Laser Therapy

- Excimer laser phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK):

- Removes superficial opacities, scars, or infected tissue in selected cases.

Postoperative Care

- Close monitoring for graft rejection, infection, or recurrence.

- Aggressive anti-infective and anti-inflammatory regimens post-surgery.

Practical Advice for Recovery

- Avoid rubbing or touching the eye after surgery.

- Attend all follow-up appointments and report any new symptoms immediately.

- Use all prescribed drops exactly as instructed.

Emerging Innovations and Advanced Technologies

Recent years have seen significant advances in keratitis diagnosis, treatment, and prevention—offering new hope for patients with even the most severe or resistant cases.

New Diagnostic Approaches

- Rapid PCR and Next-Generation Sequencing:

- Provide pathogen identification in hours, allowing targeted therapy.

- In Vivo Confocal Microscopy:

- Noninvasive imaging to detect organisms like Acanthamoeba in real time.

Innovative Therapies

- Corneal Cross-Linking (CXL):

- Not just for keratoconus; now used as an adjunct in microbial keratitis to strengthen the cornea and reduce pathogen load.

- Antimicrobial Peptides and Nanomedicine:

- Engineered molecules and nanoparticles to overcome drug resistance.

- Biologic Eye Drops:

- Serum tears, amniotic extract, and novel growth factor formulations accelerate healing in resistant or noninfectious cases.

- Gene Therapy:

- Early research targets herpes virus and immune-modulated keratitis.

Device-Based and Remote Care Innovations

- Wearable Biosensors:

- Monitor corneal healing and detect early signs of recurrence.

- Teleophthalmology:

- Remote triage and follow-up for patients in rural or underserved areas.

Prevention and Public Health

- Smart Contact Lenses:

- Next-generation lenses incorporate antimicrobial coatings or drug delivery systems.

- Mobile Apps for Lens Hygiene:

- Digital reminders and educational tools to reduce contact lens–related keratitis.

Practical Patient Guidance

- Inquire about new diagnostic tests if traditional cultures are inconclusive.

- If you have chronic or recurrent keratitis, ask about novel therapies and clinical trials.

- Consider telemedicine for early evaluation of new symptoms, especially if access to an eye specialist is limited.

Clinical Trials and Future Directions

Ongoing research continues to push the boundaries of keratitis management, aiming to reduce vision loss, limit complications, and improve quality of life.

Current and Upcoming Clinical Trials

- Next-Generation Antimicrobials:

- Trials on new classes of antibiotics, antifungals, and antivirals with improved corneal penetration.

- Stem Cell Therapy:

- Investigating limbal stem cell transplantation for persistent epithelial defects and nonhealing ulcers.

- Biologic Agents:

- Testing recombinant growth factors, cytokine inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies for inflammatory or immune keratitis.

- Gene Editing and RNA Therapies:

- Experimental treatments targeting viral DNA or corneal repair pathways.

- Preventive Public Health Initiatives:

- Global studies on cost-effective interventions for reducing keratitis incidence, especially in high-risk regions.

How to Find and Join Clinical Trials

- Visit clinicaltrials.gov and major eye hospital websites for the latest opportunities.

- Discuss with your ophthalmologist if you’re a candidate for investigational treatments.

- Patient advocacy groups may offer additional resources and support.

Looking Ahead

- Early diagnosis and personalized medicine will increasingly guide treatment decisions.

- Smart drug delivery, biosensors, and telehealth are expected to become standard in keratitis care.

- Advances in public health education and access will reduce the global burden of corneal blindness.

Empowering Patients and Families

- Stay proactive with regular eye exams, especially if you wear contact lenses or have had keratitis before.

- Join patient forums or local support groups to share experiences and stay informed about new research.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is keratitis and what causes it?

Keratitis is inflammation of the cornea, usually caused by infection (bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic), trauma, or immune disorders. Poor contact lens hygiene and eye injuries are leading risk factors.

How is keratitis treated?

Treatment depends on the cause. Most cases require prescription eye drops—antibiotics, antivirals, or antifungals. Severe or resistant cases may need surgery. Never use steroid drops unless prescribed by an eye doctor.

Is keratitis contagious?

Some forms, especially those caused by viruses or bacteria, can be contagious. Good hygiene, not sharing personal items, and careful contact lens practices help prevent spread.

What are the warning signs of keratitis?

Symptoms include red eyes, pain, tearing, blurred vision, light sensitivity, and sometimes discharge. Seek urgent care for sudden changes or if symptoms persist more than a day.

Can keratitis cause permanent vision loss?

Yes, untreated or severe keratitis can cause corneal scarring or perforation, leading to irreversible vision loss. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are critical.

Can I prevent keratitis if I wear contact lenses?

Yes—practice excellent lens hygiene, avoid sleeping in lenses unless approved, never use tap water on contacts, and replace cases regularly.

Are there new treatments for keratitis?

Yes, recent advances include rapid diagnostic tests, cross-linking, nanomedicine, and stem cell therapies. Ask your eye specialist about new options and ongoing clinical trials.

Disclaimer:

This article is for informational purposes only and does not substitute for professional medical advice. If you have symptoms of keratitis or vision changes, seek care from an eye specialist promptly. Early treatment is the best way to preserve your vision.

If you found this article helpful, please consider sharing it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your favorite platform. Your support helps us continue providing expert eye health content to others—thank you for spreading awareness!