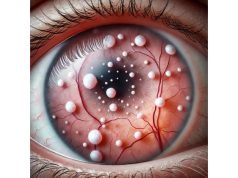

Scleral melanocytosis is a rare, benign ocular condition characterized by the presence of slate-gray or bluish pigmentation on the sclera, the white part of the eye. This pigmentation results from an increased number of melanocytes, the cells responsible for producing melanin, in the scleral tissue. Scleral melanocytosis is typically congenital, meaning it is present at birth, but it can also develop later in life. Although it is generally considered harmless and does not affect vision, its presence can be a cosmetic concern for some individuals and, in rare cases, may be associated with other ocular or systemic conditions.

Pathophysiology of Scleral Melanocytosis

To understand scleral melanocytosis, it is important to first grasp the role of melanocytes in the eye. Melanocytes are specialized cells derived from the neural crest during embryonic development. These cells are responsible for producing melanin, the pigment that gives color to the skin, hair, and eyes. In the eye, melanocytes are typically found in the uveal tract, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. However, in scleral melanocytosis, an abnormal number of melanocytes are present in the episcleral and scleral tissues.

The exact cause of scleral melanocytosis is not fully understood, but it is believed to result from a developmental anomaly during embryogenesis. During fetal development, melanocytes migrate from the neural crest to various parts of the body, including the eyes. In scleral melanocytosis, there may be an over-migration or abnormal persistence of melanocytes in the sclera, leading to the characteristic pigmentation.

Scleral melanocytosis is more common in individuals of Asian and African descent and is rarely seen in Caucasians. It is usually unilateral (affecting one eye) but can also be bilateral (affecting both eyes). The pigmentation is most often located in the sclera near the limbus, the junction between the cornea and sclera, and may extend to the surrounding conjunctiva. The coloration can vary from light gray to deep blue, depending on the depth and concentration of melanocytes.

Clinical Presentation

Scleral melanocytosis is typically asymptomatic, meaning that it does not cause any symptoms other than the visible pigmentation. The condition is usually detected during a routine eye examination or noticed by the patient or their family. The pigmentation itself is non-progressive, meaning that it does not change significantly over time. However, the appearance of scleral melanocytosis can vary depending on the lighting conditions and the angle at which the eye is viewed.

- Pigmentation: The hallmark of scleral melanocytosis is the presence of slate-gray or bluish pigmentation on the sclera. This pigmentation is usually patchy and irregular, with the affected areas appearing darker than the surrounding white sclera. The pigmentation is often most pronounced near the limbus but can extend to other parts of the sclera and conjunctiva. The color may appear more intense in natural light and may be less noticeable in dim lighting.

- Unilateral or Bilateral: Scleral melanocytosis is more commonly unilateral, affecting only one eye. However, it can also occur bilaterally, where both eyes exhibit the pigmentation. Bilateral cases are less common and may be associated with other systemic or ocular conditions.

- Congenital vs. Acquired: Scleral melanocytosis is typically congenital, meaning it is present at birth. In these cases, the pigmentation is usually noticed in infancy or early childhood. However, acquired scleral melanocytosis can develop later in life, often in response to environmental factors such as prolonged sun exposure or the use of certain medications.

- Cosmetic Concerns: While scleral melanocytosis is generally harmless, it can be a cosmetic concern for some individuals. The visible pigmentation may cause self-consciousness or lead to questions from others about the appearance of the eyes. In most cases, the pigmentation does not cause any discomfort or affect vision, but its presence may still be bothersome to the patient.

Differential Diagnosis

When scleral pigmentation is observed, it is important to differentiate scleral melanocytosis from other conditions that can cause similar appearances. These conditions include:

- Nevus of Ota: Nevus of Ota, also known as oculodermal melanocytosis, is a condition characterized by hyperpigmentation of the skin and sclera. Unlike scleral melanocytosis, nevus of Ota usually affects both the skin and the eye and is more commonly associated with other complications, such as an increased risk of glaucoma and uveal melanoma.

- Blue Sclera: Blue sclera is a condition in which the sclera appears blue due to thinning of the scleral tissue, allowing the underlying uveal tissue to show through. Blue sclera is often associated with connective tissue disorders, such as osteogenesis imperfecta, and can be distinguished from scleral melanocytosis by its diffuse, uniform appearance rather than patchy pigmentation.

- Primary Acquired Melanosis (PAM): PAM is a condition characterized by the presence of flat, pigmented lesions on the conjunctiva. Unlike scleral melanocytosis, PAM lesions are usually acquired later in life and can be a precursor to malignant melanoma of the conjunctiva. PAM requires close monitoring and, in some cases, biopsy to rule out malignancy.

- Melanoma: Ocular melanoma is a malignant tumor of the melanocytes in the eye. It can present as a pigmented lesion on the sclera, conjunctiva, or uveal tract. Melanoma is distinguished from scleral melanocytosis by its more nodular appearance, rapid growth, and potential to cause symptoms such as pain or vision changes. Any suspicious pigmented lesion should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist to rule out malignancy.

Associated Conditions

While scleral melanocytosis is generally benign, it is important to be aware of its potential associations with other ocular and systemic conditions. These associations include:

- Uveal Melanoma: Although rare, there is a slight increased risk of developing uveal melanoma in individuals with scleral melanocytosis. Uveal melanoma is a malignant tumor that arises from the melanocytes in the uveal tract, including the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Regular monitoring by an ophthalmologist is recommended for patients with scleral melanocytosis to detect any early signs of melanoma.

- Glaucoma: Scleral melanocytosis, particularly when associated with nevus of Ota, has been linked to an increased risk of glaucoma. Glaucoma is a condition characterized by increased intraocular pressure, which can lead to optic nerve damage and vision loss. Patients with scleral melanocytosis should undergo regular eye examinations to monitor intraocular pressure and assess the health of the optic nerve.

- Dermal Melanocytosis: In some cases, scleral melanocytosis may be associated with dermal melanocytosis, a condition characterized by the presence of blue or gray pigmentation on the skin. Dermal melanocytosis is more common in individuals of Asian or African descent and is usually benign. However, it can be associated with certain congenital syndromes, such as Sturge-Weber syndrome or neurofibromatosis.

- Ocular Inflammation: While scleral melanocytosis itself does not cause inflammation, the presence of abnormal melanocytes in the sclera may predispose some individuals to episodes of ocular inflammation, such as episcleritis or scleritis. These conditions can cause redness, pain, and discomfort in the eye and may require treatment with anti-inflammatory medications.

Understanding the characteristics of scleral melanocytosis and its potential associations is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management. While the condition is typically benign, regular monitoring by an ophthalmologist is recommended to ensure that no complications or associated conditions develop.

Diagnostic Methods

Diagnosing scleral melanocytosis involves a thorough clinical evaluation, including a detailed patient history, physical examination, and, in some cases, additional diagnostic tests. The goal of the diagnostic process is to confirm the presence of scleral melanocytosis, differentiate it from other pigmented ocular conditions, and identify any associated ocular or systemic conditions that may require further management.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing scleral melanocytosis is a comprehensive eye examination conducted by an ophthalmologist. The examination typically includes:

- Visual Inspection: The ophthalmologist will perform a visual inspection of the sclera to assess the presence, distribution, and color of the pigmentation. Scleral melanocytosis is characterized by slate-gray or bluish patches on the sclera, often concentrated near the limbus. The pigmentation is usually non-elevated and does not affect the cornea or iris.

- Slit-Lamp Biomicroscopy: Slit-lamp biomicroscopy is a key tool in the evaluation of scleral melanocytosis. This examination allows the ophthalmologist to closely examine the anterior segment of the eye, including the sclera, conjunctiva, and cornea. Slit-lamp examination can help confirm the diagnosis by revealing the characteristic pigmentation and assessing its depth and extent.

- Fundoscopy: Fundoscopy, also known as ophthalmoscopy, is used to examine the posterior segment of the eye, including the retina, optic disc, and choroid. Although scleral melanocytosis primarily affects the anterior sclera, fundoscopy is important for assessing the overall health of the eye and identifying any associated conditions, such as uveal melanoma.

Imaging Studies

In some cases, imaging studies may be used to further evaluate scleral melanocytosis and rule out other conditions. These imaging techniques include:

- Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM): UBM is an imaging technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to create detailed images of the anterior segment of the eye. UBM can be used to assess the depth and extent of pigmentation in scleral melanocytosis, particularly when the pigmentation is located deep within the scleral tissue. UBM can help differentiate scleral melanocytosis from other conditions such as blue sclera or anterior staphyloma, where scleral thinning is a concern.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique that provides high-resolution cross-sectional images of the eye’s tissues. While it is more commonly used to evaluate the retina and optic nerve, anterior segment OCT can be useful in assessing the layers of the sclera and conjunctiva, allowing for a better understanding of the pigmentation’s depth and structural characteristics.

- Anterior Segment Photography: High-resolution photography of the anterior segment can be useful for documenting the appearance of scleral melanocytosis over time. This can help in monitoring the stability of the pigmentation and detecting any changes that may indicate the development of an associated condition, such as melanoma.

Differential Diagnosis and Additional Tests

Given that scleral pigmentation can be a feature of several other ocular conditions, it is important to perform additional tests to rule out more serious causes, such as melanoma or primary acquired melanosis (PAM). These tests may include:

- Biopsy: In rare cases where the pigmentation is atypical, changes in size or color over time, or is associated with other suspicious features, a biopsy may be performed to obtain a tissue sample for histopathological examination. This is particularly important if there is concern about the possibility of ocular melanoma. The biopsy can help determine whether the lesion is benign or malignant and guide further management.

- Genetic Testing: In cases where scleral melanocytosis is associated with other congenital conditions, such as dermal melanocytosis or neurofibromatosis, genetic testing may be recommended. Genetic testing can provide information about the underlying syndrome and its associated risks, helping to guide long-term management and monitoring.

- Intraocular Pressure Measurement: Because scleral melanocytosis has been associated with an increased risk of glaucoma, measuring intraocular pressure (IOP) is an important part of the diagnostic workup. Elevated IOP may indicate the presence of glaucoma, necessitating further evaluation and treatment to prevent optic nerve damage and vision loss.

Monitoring and Follow-Up

While scleral melanocytosis is typically benign and non-progressive, regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist is recommended to monitor for any changes in the pigmentation or the development of associated conditions. During follow-up visits, the ophthalmologist will repeat the clinical examination and imaging studies as needed to ensure that the condition remains stable.

In patients with unilateral or bilateral scleral melanocytosis, it is particularly important to monitor for signs of uveal melanoma or glaucoma. Early detection of these conditions can significantly improve outcomes and prevent serious complications.

Scleral Melanocytosis Management

Scleral melanocytosis is generally considered a benign condition, and in most cases, it does not require active treatment. However, management strategies may vary depending on the patient’s concerns, the presence of associated conditions, and any potential risk factors that might necessitate intervention.

Observation and Monitoring

For the majority of patients with scleral melanocytosis, observation and regular monitoring are the primary management approaches. Since the pigmentation is usually stable and non-progressive, periodic eye examinations are recommended to ensure that no changes occur over time. During these follow-up visits, an ophthalmologist will evaluate the pigmentation, check for any new symptoms, and monitor for complications such as glaucoma or uveal melanoma.

- Frequency of Monitoring: The frequency of follow-up visits will depend on the individual patient’s risk factors and the presence of any associated conditions. For patients with isolated scleral melanocytosis and no other ocular abnormalities, annual eye examinations may be sufficient. However, for those with associated conditions like nevus of Ota or a family history of melanoma, more frequent monitoring may be recommended.

- Imaging and Documentation: Anterior segment photography or other imaging techniques such as ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) can be used to document the appearance of scleral melanocytosis over time. This allows for the detection of any subtle changes that might indicate the need for further evaluation or intervention.

Management of Associated Conditions

While scleral melanocytosis itself is not harmful, it can be associated with other ocular or systemic conditions that may require treatment. Addressing these associated conditions is an important aspect of managing patients with scleral melanocytosis.

- Glaucoma Management: Patients with scleral melanocytosis, particularly those with associated conditions like nevus of Ota, may be at an increased risk of developing glaucoma. Glaucoma is a serious condition that can lead to optic nerve damage and vision loss if not properly managed. In such cases, regular intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements are crucial. If elevated IOP is detected, treatment with medications such as prostaglandin analogs, beta-blockers, or carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may be initiated to lower the pressure and protect the optic nerve. In more advanced cases, surgical interventions such as trabeculectomy or laser therapy may be required.

- Monitoring for Uveal Melanoma: Although rare, scleral melanocytosis can be associated with an increased risk of uveal melanoma, particularly in individuals with extensive ocular pigmentation or nevus of Ota. Regular monitoring by an ophthalmologist is essential to detect any early signs of melanoma. If a suspicious lesion is identified, further evaluation, including biopsy or advanced imaging, may be necessary. In cases where uveal melanoma is diagnosed, treatment options may include radiation therapy, laser therapy, or surgical removal of the tumor, depending on its size and location.

- Cosmetic Concerns: While scleral melanocytosis is not harmful, some patients may be concerned about the cosmetic appearance of the pigmentation. In such cases, it is important for the ophthalmologist to provide reassurance and education about the benign nature of the condition. If the pigmentation is causing significant distress, cosmetic options such as colored contact lenses may be considered to mask the appearance of the scleral pigmentation. However, these options should be discussed carefully with the patient, considering the potential risks and benefits.

Surgical and Laser Interventions

In rare cases where scleral melanocytosis is associated with a significant cosmetic concern or if there is suspicion of malignancy, surgical or laser interventions may be considered. These interventions are generally reserved for specific cases and are not commonly required.

- Laser Therapy: Laser therapy can be used to reduce the appearance of pigmented lesions on the sclera or conjunctiva. This approach is more commonly used for conditions like primary acquired melanosis (PAM) but may be considered for scleral melanocytosis if the pigmentation is particularly prominent or bothersome. However, laser therapy carries risks, including potential damage to the surrounding ocular tissues, and should be performed by an experienced ophthalmologist.

- Surgical Excision: Surgical excision of pigmented lesions is typically reserved for cases where there is a concern about malignancy or when the pigmentation is associated with other pathological changes. This approach involves the removal of the pigmented tissue and may be followed by histopathological examination to rule out melanoma. Surgical excision is usually not necessary for benign scleral melanocytosis, but it may be considered in select cases.

Patient Education and Reassurance

One of the most important aspects of managing scleral melanocytosis is patient education and reassurance. Patients should be informed about the benign nature of the condition and the importance of regular monitoring to detect any potential complications. Providing patients with accurate information can help alleviate concerns and ensure that they understand the reasons for ongoing follow-up care.

For patients with associated conditions like nevus of Ota, it is important to educate them about the increased risks of glaucoma and uveal melanoma, as well as the signs and symptoms to watch for. Encouraging patients to report any new symptoms, such as changes in vision, pain, or noticeable changes in the appearance of the pigmentation, is crucial for early detection and intervention.

Overall, the management of scleral melanocytosis focuses on observation, monitoring for associated conditions, and addressing any cosmetic or psychological concerns that may arise. By providing comprehensive care and patient education, ophthalmologists can help ensure that individuals with scleral melanocytosis maintain good ocular health and quality of life.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach” by Jack J. Kanski: This comprehensive book provides an in-depth overview of various ocular conditions, including scleral melanocytosis. It is a valuable resource for ophthalmologists and students looking to expand their knowledge of eye diseases.

- “Color Atlas of Ophthalmology” by Amar Agarwal: This atlas offers detailed images and descriptions of ocular conditions, including scleral melanocytosis. It serves as an excellent reference for identifying and understanding different eye disorders.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO provides extensive resources and guidelines for the diagnosis and management of ocular conditions, including scleral melanocytosis. It offers educational materials for both healthcare professionals and patients.

- National Eye Institute (NEI): Part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the NEI offers comprehensive information on eye diseases, including rare conditions like scleral melanocytosis. The institute supports research and provides valuable resources for patients and clinicians alike.

- Ocular Melanoma Foundation (OMF): Although scleral melanocytosis is generally benign, the OMF provides resources and support for conditions associated with ocular melanocytes, including uveal melanoma. It offers patient education, research updates, and support networks.