What is vitritis?

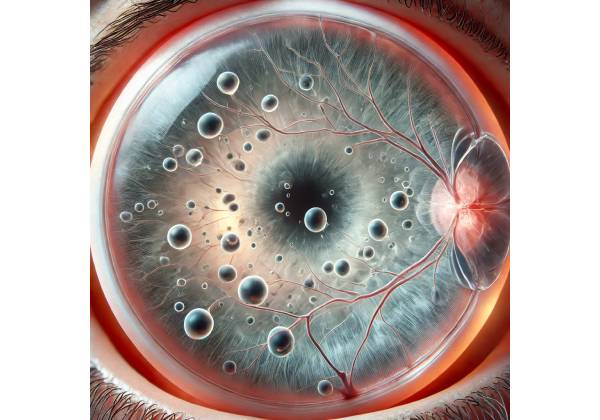

Vitritis, also known as intermediate uveitis, is an ocular condition that causes inflammation of the vitreous humor, a clear, gel-like substance that fills the space between the lens and the retina in the eye. This condition is a type of uveitis, which is defined as inflammation of the uveal tract—the middle layer of the eye that contains the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. Vitritis primarily affects the vitreous body, but it is frequently part of a larger inflammatory process that affects other parts of the eye, such as the retina or optic nerve.

Anatomy of the Vitreous Body

To fully understand vitritis, one must first understand the anatomy and function of the vitreous body. The vitreous humor accounts for approximately 80% of the eye’s volume and provides structural support to keep the eye’s shape. The vitreous is mostly water (98-99%), but it also contains collagen fibers, hyaluronic acid, and a few cells called hyalocytes. These elements give the vitreous its gel-like consistency and contribute to its role in supporting the retina as well as transmitting light from the lens to the retina, which processes visual information.

Under normal conditions, the vitreous humor is avascular, which means it lacks blood vessels. This lack of vasculature is critical to maintaining the eye’s transparency, which is required for clear vision. However, in the presence of inflammation, cells and other inflammatory mediators can infiltrate the vitreous, causing cloudiness and visual disturbances, which are characteristic of vitritis.

Causes of Vitritis

A variety of underlying conditions, ranging from infectious agents to autoimmune disorders, can cause vitritis. The inflammation may be limited to the eye or be part of a larger inflammatory process. Understanding the potential causes of vitritis is critical for a correct diagnosis and effective treatment.

- Infectious Causes: Bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites are all potential causes of vitritis. Some of the most common infectious causes are:

- Toxoplasmosis: A parasitic infection caused by Toxoplasma gondii, toxoplasmosis is one of the most common infectious causes of vitritis. The parasite can infect the retina and vitreous, resulting in ocular toxoplasmosis, a condition characterized by vitritis.

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV): CMV is a viral infection that can cause severe inflammation in immunocompromised people, including those with HIV/AIDS. CMV retinitis, a condition characterized by retinal inflammation, frequently results in vitritis as the infection spreads to the vitreous humor.

- Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, can infect the eye, resulting in tuberculous uveitis, which may include vitritis. This type of uveitis is more common in areas where tuberculosis is prevalent.

- Syphilis: The bacterium responsible for syphilis, Treponema pallidum, can cause ocular syphilis, a serious condition that can result in vitritis. This condition is usually present in the secondary or tertiary stages of syphilis and requires immediate treatment to avoid complications.

- Candida: Fungal infections such as candidiasis can cause vitritis, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Candida species can infect the eye, causing endophthalmitis, a serious inflammatory condition that can affect the vitreous.

- Autoimmune and Inflammatory Conditions: Vitritis can also be caused by autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, in which the immune system incorrectly attacks its own tissues, including the eye. These conditions include the following:

- Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease in which granulomas (clusters of inflammatory cells) form in a variety of organs, including the eyes. Ocular sarcoidosis can cause vitritis, which is often associated with other types of uveitis.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): MS is a chronic autoimmune disease that affects the central nervous system, specifically the optic nerves. While vitritis is not a direct result of MS, patients with the condition may develop intermediate uveitis, which includes vitritis as part of the inflammation.

- Behçet’s Disease: Behçet’s disease is a rare, chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by inflammation of blood vessels throughout the body, including the eyes. Ocular involvement can cause vitritis, as well as other types of uveitis.

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Syndrome is an autoimmune disease that affects the eyes, skin, and nervous system. VKH in the eyes can cause uveitis and vitritis as part of a larger inflammatory response.

- Idiopathic Vitritis: Idiopathic vitritis occurs when vitritis develops for no apparent reason. Despite extensive investigation, the underlying cause of the inflammation remains unknown. Idiopathic vitritis is frequently treated in the same way as other types of uveitis, with the goal of reducing inflammation and preserving vision.

Symptoms of Vitritis

Vitritis symptoms can vary depending on the severity of the inflammation and whether or not there are any underlying conditions. Common symptoms include:

- Floaters: One of the most common signs of vitritis is the sudden appearance of floaters—small, dark spots or threads that move across the visual field. Inflammatory cells and debris within the vitreous humor cast shadows on the retina, causing these floaters. The floaters can be especially bothersome, and their number may increase as the inflammation progresses.

- Blurred Vision: Vitritis can cause significant blurring of vision due to the cloudiness of the vitreous humor. Inflammatory cells, proteins, and other debris can obstruct light passage through the vitreous, resulting in reduced visual acuity. The severity of the inflammation determines the extent of visual impairment, which can range from mild blurring to severe vision loss.

- Photophobia (Light Sensitivity): Patients with vitritis frequently develop photophobia, a condition in which bright lights cause discomfort or pain. This light sensitivity is a common feature of uveitis, and it is thought to be caused by inflammation of the eye’s internal structures.

- Redness and Pain: Although vitritis is not usually associated with significant redness or pain, these symptoms may occur if the inflammation spreads to other parts of the eye, such as the anterior chamber or the sclera. In such cases, the eye may appear red, and patients may feel varying levels of ocular discomfort.

- Decreased Visual Field: In severe cases of vitritis, patients may notice a reduction in their visual field, especially in the peripheral areas. This can happen if the inflammation is accompanied by other ocular conditions like retinal detachment or macular edema, which can affect the entire field of vision.

- Difficulty Seeing in Low Light: Vitritis can make it difficult to see in low light because the cloudiness of the vitreous humor reduces the amount of light that reaches the retina. This symptom can be especially troubling for patients who must perform tasks in low-light conditions.

Complications of Vitritis

If left untreated, vitritis can lead to serious complications, including permanent vision loss. Some of the most concerning complications are:

- Cystoid Macular Edema (CME) is a condition in which fluid accumulates in the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp, detailed vision. Inflammatory processes associated with vitritis can lead to CME, which can cause significant vision impairment if not treated promptly.

- Retinal Detachment: In severe cases, the inflammation associated with vitritis can cause the retina to separate from its underlying layers. Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that necessitates prompt surgical intervention to avoid permanent vision loss.

- Glaucoma: Chronic inflammation in the eye can cause secondary glaucoma, which is characterized by increased intraocular pressure and optic nerve damage. If glaucoma develops as a result of vitritis, long-term management may be required to maintain vision.

- Cataract Formation: Prolonged inflammation or the use of corticosteroids to treat vitritis can increase the risk of cataract formation, which occurs when the lens of the eye becomes cloudy, causing further vision impairment.

Risk Factors for Vitritis

Several factors can raise the risk of developing vitritis, including:

- Autoimmune Disorders: People who have autoimmune conditions like sarcoidosis, multiple sclerosis, or Behçet’s disease are more likely to develop vitritis because their immune systems attack their own tissues, including the eye.

- Infectious Diseases: People with a history of infections such as toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, or syphilis are more likely to develop vitritis, especially if the infections are not properly treated.

- Immunocompromised Status: Patients with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or on immunosuppressive therapy, are more vulnerable to infections that can cause vitritis.

- Previous Eye Surgery or Trauma: People who have had eye surgery or suffered ocular trauma may be more likely to develop vitritis, especially if the surgery or injury causes inflammation or infection.

Diagnostic Tools for Vitritis Detection

Vitritis requires a thorough clinical evaluation, which includes a detailed patient history, physical examination, and specialized imaging techniques. The goal is to detect inflammation in the vitreous humor, identify the underlying cause, and evaluate any associated ocular or systemic conditions.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing vitritis is a comprehensive clinical examination by an ophthalmologist or retina specialist. The exam typically includes the following components:

- Patient History: The clinician begins by gathering a thorough patient history, concentrating on the onset, duration, and nature of symptoms such as floaters, blurred vision, and light sensitivity. The history will also include any previous eye conditions, surgeries, trauma, or systemic diseases that may be associated with vitritis, such as autoimmune disorders or infections. Understanding the patient’s medical history allows the clinician to identify possible causes and risk factors for vitritis.

- Visual Acuity Test: A visual acuity test is used to determine the level of visual impairment. This test requires reading letters from a standardized chart from a set distance. The results provide a baseline measure of the patient’s visual function, which is useful for tracking the condition’s progression and the effectiveness of therapy.

- Slit-Lamp Examination: A slit-lamp examination is a valuable diagnostic tool for evaluating the anterior structures of the eye, such as the cornea, lens, and anterior chamber. During this examination, the clinician can use special lenses to visualize the vitreous humor and detect any inflammatory cells (known as “vitreous cells”) or debris clumps that are indicative of vitritis. The slit-lamp examination provides a thorough evaluation of the eye’s internal environment, which is critical for diagnosing vitritis.

- Dilated Fundus Examination: To thoroughly examine the retina and posterior segment of the eye, the clinician will perform a dilated fundus exam. Eye drops dilate the pupil, allowing the clinician to see the back of the eye through an ophthalmoscope. This examination aids in detecting any retinal involvement, such as macular edema, retinal detachment, or vasculitis, which may coexist with vitritis.

Imaging Techniques

In addition to the clinical examination, imaging techniques are frequently used to provide a more detailed evaluation of the vitreous humor and associated ocular structures. These methods are especially useful in confirming the diagnosis of vitritis and determining any complications or underlying causes.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and vitreous. OCT is especially useful for detecting subtle changes in the retina, such as cystoid macular edema or vitreomacular traction, which can be associated with vitritis. OCT can also help assess the severity of vitreous inflammation and track treatment response over time.

- Ultrasound B-Scan: If the vitreous is too cloudy or opaque to examine directly with a slit-lamp or ophthalmoscope, an ultrasound B-scan may be performed. This imaging technique employs sound waves to generate cross-sectional images of the eye, allowing the clinician to see the vitreous humor and detect any structural abnormalities associated with vitritis, such as retinal detachment.

- Fluorescein Angiography: When retinal vasculitis or neovascularization is suspected, fluorescein angiography can be used to examine the retinal blood vessels. This procedure involves injecting a fluorescent dye into the bloodstream and photographing the dye as it circulates through the retinal vessels. Fluorescein angiography can help identify areas of leakage, blockages, or abnormal blood vessel growth that may be contributing to vitritis inflammation.

Lab Tests

Laboratory tests may be necessary to determine the underlying cause of vitritis, especially if an infectious or autoimmune etiology is suspected. These tests may include:

- Blood Tests: Blood tests can be used to look for systemic infections, autoimmune markers, or inflammatory conditions that may be related to vitritis. When syphilis, tuberculosis, or HIV are suspected, tests are frequently performed. Autoimmune markers such as antinuclear antibodies (ANA) or HLA-B27 may be tested when autoimmune diseases are suspected.

- Aqueous or Vitreous Tap: In some cases, a small sample of aqueous humor (from the anterior chamber) or vitreous humor may be taken for analysis. This procedure, known as a tap, can aid in the identification of infectious agents such as bacteria or viruses, as well as inflammatory cells found in the vitreous. A laboratory analyzes the sample to determine the specific cause of the inflammation, which guides the clinician in selecting the best treatment.

Best Practices for Vitritis Management

Vitritis treatment entails addressing both the inflammation in the vitreous humor and the underlying cause of the condition. Treatment strategies differ according to the severity of the inflammation, the presence of any associated complications, and whether the vitritis is part of a larger systemic disease. The primary goals of management are to reduce inflammation, relieve symptoms, prevent complications, and, if possible, treat the underlying cause to avoid recurrence.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the primary treatment for vitritis, especially when the inflammation is non-infectious. These potent anti-inflammatory medications can be administered in a variety of ways, depending on the severity and location of the inflammation:

- Topical Corticosteroids: In mild cases of vitritis or when inflammation is limited to the anterior segment of the eye, topical corticosteroid eye drops may be prescribed. These drops help to reduce inflammation by inhibiting the immune response within the eyes. However, due to topical steroids’ limited penetration into the posterior segment of the eye, they are frequently insufficient to treat more severe or posterior inflammation.

- Periocular or Intravitreal Injections: Corticosteroids can be given periocularly (around the eye) or intravitreally (into the vitreous humor) to treat more severe or posterior vitritis. These injections administer high concentrations of the drug directly to the site of inflammation, resulting in a more effective and targeted treatment. Triamcinolone acetonide is one of the most commonly used corticosteroids for these injections. Intravitreal injections are particularly effective in rapidly reducing inflammation and are frequently used when there is significant visual impairment.

- Oral or Systemic Corticosteroids: When vitritis is associated with a systemic inflammatory or autoimmune condition, oral or systemic corticosteroids may be necessary. These medications work throughout the body to reduce inflammation and are frequently used when other types of steroid therapy fail. Systemic steroids are typically prescribed for a limited time to control acute inflammation, with the dosage gradually tapering to reduce side effects.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

When vitritis is associated with an underlying autoimmune disorder or when corticosteroids alone are ineffective at controlling inflammation, immunosuppressive therapy may be required. These medications inhibit the immune system’s activity, lowering the inflammatory response. Common immunosuppressive agents used in the management of vitritis are:

- Methotrexate: Methotrexate is a widely used immunosuppressant that can help control chronic or severe inflammation. It is frequently used as a steroid-sparing agent, allowing lower doses of corticosteroids to be administered, lowering the risk of side effects.

- Azathioprine: Azathioprine is another immunosuppressive drug used to treat vitritis, especially when it is accompanied by systemic autoimmune conditions. It works by inhibiting immune cell proliferation, which reduces inflammation.

- Biologic Agents: In more resistant or severe cases, biologic agents like infliximab or adalimumab may be used. These drugs reduce inflammation by targeting specific immune system components, like TNF-α. Biologic agents are frequently reserved for patients who have not responded to standard immunosuppressive therapy.

Antibiotics and antivirals

When an infectious agent causes vitritis, proper antimicrobial treatment is required. The chosen antibiotic or antiviral medication depends on the identified or suspected pathogen:

- Antibiotics: For bacterial infections like tuberculosis or syphilis, specific antibiotics are prescribed based on the organism’s sensitivity. For example, tuberculosis is typically treated with a cocktail of anti-tubercular drugs, whereas syphilis is typically treated with penicillin.

- Antivirals: Antiviral medications, such as ganciclovir or valganciclovir, are used to control viral infections like cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis and reduce inflammation. These medications can be given orally, intravenously, or intravitreally, depending on the severity of the infection.

- Antifungals: Amphotericin B or voriconazole are used to treat fungal infections such as candidiasis. To effectively treat the infection, these medications are frequently given systemically or as an intravitreal injection.

Vitrectomy

In severe cases of vitritis, especially when there is a risk of complications such as retinal detachment or when the inflammation is resistant to medical treatment, a surgical procedure known as vitrectomy may be necessary. Vitrectomy is the surgical removal of the vitreous humor, as well as any inflammatory cells, debris, or infectious material from the eye. This procedure not only clears the vitreous, but it also provides direct access to the retina for treatment of any underlying conditions.

Vitrectomy is usually performed under local or general anesthesia, and it may be combined with other procedures, such as laser photocoagulation, to treat any associated retinal abnormalities. While vitrectomy can be extremely effective in treating severe vitritis, it is typically reserved for cases where medical therapy has failed or there is a significant risk to vision.

Long-Term Management and Follow-up

Managing vitritis frequently necessitates long-term monitoring and follow-up to ensure that the inflammation is under control and that it does not recur. Patients with chronic or recurrent vitritis may require ongoing immunosuppressive therapy as well as regular eye exams to check for complications like cataracts, glaucoma, or macular edema. Close collaboration between ophthalmologists and other healthcare providers, such as rheumatologists or infectious disease specialists, is frequently required to manage the underlying systemic conditions that can cause vitritis.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice” by Robert B. Nussenblatt and Scott M. Whitcup

- This authoritative text provides comprehensive coverage of uveitis, including vitritis, offering insights into the diagnosis, management, and underlying causes of ocular inflammation.

- “Ocular Immunology in Health and Disease” by Steve R. Heinemann

- A detailed exploration of the immune mechanisms involved in eye diseases, this book is an excellent resource for understanding the complex interactions that lead to conditions like vitritis.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO)

- The AAO offers a wealth of resources on vitritis and related conditions, including patient education materials, clinical guidelines, and updates on the latest research in ocular inflammation.

- Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation (OIUF)

- The OIUF is dedicated to supporting research, education, and patient care for those affected by uveitis and related ocular inflammatory conditions. Their website provides information on vitritis, support resources, and connections to specialist care.