The appendix is a small, tube-like structure attached to the beginning of the large intestine. Though once considered a vestigial organ with little to no function, recent research suggests that it may play a role in immune regulation and maintaining gut flora. Understanding the anatomy, potential functions, common disorders, and treatment options for the appendix is essential for a comprehensive grasp of digestive health. This guide delves into its intricate structure, examines its possible contributions to immunity and gut balance, and explores current strategies for diagnosing and managing appendiceal conditions—all while offering practical tips for maintaining overall digestive wellness.

Table of Contents

- Structural Anatomy Overview

- Functional Dynamics and Roles

- Appendiceal Disorders & Complications

- Diagnostic Approaches & Evaluations

- Therapeutic Strategies & Treatments

- Nutritional and Supplementary Support

- Lifestyle Recommendations for Optimal Health

- Authoritative Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

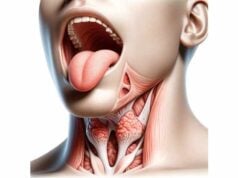

Structural Anatomy Overview

The appendix is a narrow, blind-ended tube that extends from the cecum, located in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. Its position near the ileocecal valve and within the right iliac fossa makes it an important landmark during clinical examinations. Although its length can vary widely—from 1 to 8 inches—the average appendix measures between 2 and 4 inches. Despite its diminutive size and tubular shape, the appendix is composed of several distinct layers that mirror those of the large intestine and contribute to its potential immune functions.

Location and Physical Configuration

- Positioning:

The appendix is situated in the lower right portion of the abdomen, emerging from the cecum at the junction where the small and large intestines meet. Its typical location in the right iliac fossa is crucial during diagnostic procedures, particularly when evaluating patients with suspected appendicitis. - Variability:

The appendix can adopt various positions, such as retrocecal (behind the cecum), pelvic (directed toward the pelvis), subcecal, or even preileal. This variability may affect symptom presentation and complicate the diagnosis of inflammatory conditions.

Layered Structural Composition

The wall of the appendix is organized into four main layers:

- Mucosa:

The innermost lining is similar to that of the colon, featuring a mucosal surface rich in lymphoid follicles. These collections of immune cells are believed to contribute to local gut immunity and pathogen surveillance. - Submucosa:

Beneath the mucosa lies a layer of connective tissue that houses blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. This supportive layer not only nourishes the mucosa but also facilitates the transport of immune cells. - Muscularis Externa:

The muscular layer is composed of two distinct arrangements of smooth muscle fibers—an inner circular and an outer longitudinal layer. These muscles enable modest peristaltic movements, although the appendix is not primarily involved in propulsion of intestinal contents. - Serosa:

The outermost covering is a thin serous membrane that protects the appendix and allows for smooth movement within the abdominal cavity.

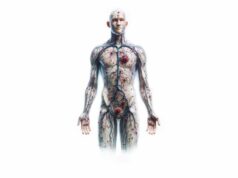

Vascular and Lymphatic Networks

- Blood Supply:

The appendicular artery, a branch of the ileocolic artery (itself a branch of the superior mesenteric artery), provides the essential blood supply to the appendix. This artery travels through the mesoappendix—a small mesentery that connects the appendix to the ileum and cecum. - Venous Drainage:

Venous return occurs through the appendicular vein, which drains into the ileocolic vein before joining the superior mesenteric vein and ultimately the portal vein. - Lymphatic Drainage:

The appendix contains abundant lymphoid tissue, and its lymphatic drainage primarily routes to the ileocolic lymph nodes. This extensive lymphatic network underlines its potential role in immune functions.

Neural Innervation

The appendix receives both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. Preganglionic sympathetic fibers, derived from the superior mesenteric plexus, and parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve innervate the structure. This dual innervation is significant in understanding the presentation of pain—initially diffuse and later localized—as inflammation progresses.

Summary of Anatomical Insights

The detailed anatomy of the appendix, from its variable position and layered wall structure to its rich vascular and lymphatic networks, highlights its complex design. Although historically labeled as vestigial, the appendix’s structure supports potential immunological and microbial reservoir functions, paving the way for a reconsideration of its role in overall digestive health.

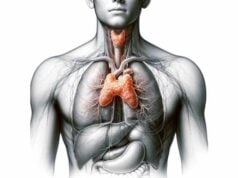

Functional Dynamics and Roles

For many years, the appendix was dismissed as a redundant organ; however, emerging evidence suggests it may play a supportive role in immune function and the maintenance of gut flora. This section explores the possible physiological functions of the appendix and its contributions to gastrointestinal health.

Immune Surveillance and Response

The appendix is densely populated with lymphoid follicles, akin to gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). This suggests that the organ may serve as a site for:

- Antibody Production:

The lymphoid cells in the mucosa help generate antibodies that are vital for neutralizing pathogens encountered in the gut. - Immune Education:

During early life, the appendix is particularly active, potentially educating the immune system to distinguish between harmful pathogens and benign or beneficial bacteria.

Reservoir for Beneficial Gut Bacteria

One of the most compelling theories regarding the appendix is its role as a safe haven for commensal bacteria:

- Microbial Reservoir:

In times of gastrointestinal distress—such as after bouts of severe diarrhea or infection—the appendix may act as a repository for beneficial bacteria. These microbes can repopulate the colon and help restore the normal balance of the gut microbiome. - Protection Against Pathogens:

By maintaining a reservoir of healthy bacteria, the appendix may prevent the overgrowth of harmful organisms, thereby supporting overall digestive and immune health.

Developmental and Evolutionary Considerations

The relative size and activity of the appendix during early life indicate its potential significance during development:

- Fetal and Early Childhood Roles:

In fetuses and young children, the appendix is proportionately larger, and its lymphoid tissue is highly active. This suggests that it may have a role in establishing the immune system’s tolerance to gut bacteria. - Evolutionary Perspective:

Some evolutionary biologists theorize that the appendix was once part of a larger cecum used by herbivorous ancestors to digest cellulose-rich plant material. As dietary habits evolved, the primary digestive role diminished, but its immunological and microbial functions may have been retained.

Protective and Regulatory Functions

Beyond its immunological role, the appendix might contribute to maintaining gut homeostasis in other ways:

- Barrier Function:

By harboring beneficial bacteria and supporting immune cell activity, the appendix may help prevent the translocation of pathogens from the gut into the bloodstream. - Regulation of Gut Motility:

Although not a primary driver of peristalsis, the appendix’s location at the junction of the small and large intestines suggests it could influence local gut motility and the flow of intestinal contents.

Recap of Functional Roles

The appendix appears to serve several important functions beyond its historical classification as vestigial. Its roles in immune surveillance, microbial storage, and possibly even in regulating gut motility underscore its potential contribution to maintaining gastrointestinal and systemic health. While research continues to clarify these roles, the evidence supports a reconsideration of the appendix as a potentially beneficial organ.

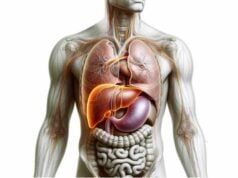

Prevalent Appendix Conditions & Complications

A range of disorders can affect the appendix, with appendicitis being the most common. This section reviews the prevalent conditions, their causes, symptoms, and clinical implications, as well as the potential complications that can arise if these conditions are not managed promptly.

Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is a sudden inflammation of the appendix and is a leading cause of abdominal surgical emergencies.

- Etiology:

The inflammation is often triggered by obstruction of the appendiceal lumen due to fecaliths (hardened stool), lymphoid hyperplasia, or, in rare cases, foreign bodies. Obstruction leads to increased intraluminal pressure, compromised blood flow, bacterial overgrowth, and subsequent infection. - Clinical Presentation:

Patients typically report initial, vague periumbilical pain that eventually localizes to the lower right quadrant (McBurney’s point). Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and low-grade fever. - Complications:

If not treated promptly, the inflamed appendix may perforate, causing peritonitis (infection of the abdominal cavity) or leading to the formation of an abscess.

Appendiceal Tumors

Though relatively rare, tumors of the appendix can range from benign carcinoid tumors to malignant adenocarcinomas and mucinous neoplasms.

- Types and Prevalence:

Carcinoid tumors are the most commonly encountered appendiceal neoplasms. They are usually small, slow-growing, and often discovered incidentally during appendectomy. More aggressive forms, such as adenocarcinomas, though uncommon, require extensive surgical intervention. - Clinical Manifestations:

Tumors may be asymptomatic or present with symptoms similar to appendicitis. Larger lesions can cause obstruction, bleeding, or even metastatic spread. - Management:

Treatment depends on tumor type and stage; small, benign tumors may be managed with simple appendectomy, whereas larger or malignant tumors might necessitate a right hemicolectomy and adjuvant therapy.

Mucocele of the Appendix

A mucocele is characterized by an abnormal accumulation of mucus within the appendix, which can be either benign or associated with neoplastic changes.

- Pathogenesis:

Obstruction of the appendiceal lumen, often due to neoplastic processes such as cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinomas, leads to mucus buildup and gradual distention of the appendix. - Clinical Features:

Some patients may remain asymptomatic, while others experience vague abdominal pain. If a mucocele ruptures, it can lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei—a condition where mucinous material disseminates throughout the abdominal cavity. - Diagnosis and Treatment:

Imaging studies (ultrasound, CT scan) can identify a fluid-filled, distended appendix. Surgical removal is the treatment of choice, with careful handling to prevent rupture.

Appendiceal Abscess

An appendiceal abscess develops when the inflamed appendix perforates, and the body attempts to contain the infection by forming a localized collection of pus.

- Pathophysiology:

The abscess forms as the immune system walls off the infection, resulting in a fluid-filled mass that may be palpable in the right lower quadrant. - Symptoms:

Patients often present with persistent abdominal pain, fever, and a palpable tender mass. A history of preceding appendicitis symptoms is common. - Management:

Initial treatment involves intravenous antibiotics and, in some cases, percutaneous drainage. Once the acute phase subsides, an interval appendectomy may be performed to prevent recurrence.

Differential Diagnoses and Special Considerations

Other conditions can mimic appendiceal disorders, including:

- Mesenteric Adenitis:

Inflammation of the lymph nodes in the mesentery can present with similar symptoms, especially in children. - Gastrointestinal Infections:

Conditions like gastroenteritis may cause diffuse abdominal pain, making clinical differentiation challenging. - Gynecological Disorders:

In females, conditions such as ovarian torsion or pelvic inflammatory disease can mimic appendicitis.

Understanding the spectrum of appendiceal conditions is crucial for accurate diagnosis and timely intervention, thereby reducing the risk of severe complications.

Diagnostic Approaches & Evaluations

Accurate diagnosis of appendix-related disorders requires a comprehensive approach that integrates clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and imaging studies. This section outlines the multifaceted strategies used to assess appendiceal health and distinguish between various conditions.

Clinical Examination and History

The diagnostic journey begins with a detailed patient history and physical examination.

- Symptom Inquiry:

Physicians ask about the onset, duration, and progression of abdominal pain, with particular attention to pain migration from the periumbilical region to the lower right quadrant. Associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, fever, and anorexia are noted. - Physical Signs:

The presence of tenderness at McBurney’s point, rebound tenderness, and signs like Rovsing’s and psoas signs can indicate appendicitis. A careful examination helps differentiate appendiceal disorders from other causes of abdominal pain.

Laboratory Investigations

Lab tests support the clinical assessment by identifying markers of inflammation and infection.

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):

An elevated white blood cell count with a left shift (increased neutrophils) is commonly observed in appendicitis. - C-Reactive Protein (CRP):

Elevated CRP levels indicate systemic inflammation and, when combined with a high CBC, can strengthen the suspicion of appendiceal infection. - Other Inflammatory Markers:

Additional markers, such as procalcitonin, may also be measured in complex cases.

Imaging Techniques

Imaging plays a pivotal role in confirming the diagnosis and assessing the severity of appendiceal conditions.

- Ultrasound:

Often the first-line imaging modality, especially in children and pregnant women, ultrasound is noninvasive and radiation-free. It may reveal an enlarged, non-compressible appendix, peri-appendiceal fluid, or the presence of an abscess or mucocele. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT scans offer high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing appendicitis. They can delineate the anatomy of the appendix, detect appendicoliths (calcified deposits), and identify complications such as perforation or abscess formation. Contrast-enhanced CT provides further detail regarding surrounding tissues. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is used as an alternative to CT in populations where radiation exposure is a concern, such as in pregnant women. It offers excellent soft tissue contrast, aiding in the diagnosis of atypical appendiceal presentations.

Advanced Diagnostic Procedures

When noninvasive methods are inconclusive, more invasive diagnostic techniques may be employed.

- Diagnostic Laparoscopy:

In uncertain cases, laparoscopy allows direct visualization of the appendix and surrounding structures. It can confirm the diagnosis and facilitate immediate surgical intervention if needed. - Histopathological Examination:

In cases where appendiceal tumors or atypical conditions are suspected, tissue samples obtained during surgery are analyzed microscopically to determine the exact pathology.

Special Considerations in Diagnosis

- Pediatric and Geriatric Populations:

The clinical presentation of appendicitis may differ in children and the elderly, often leading to atypical symptoms. In these cases, imaging and careful clinical correlation become even more critical. - Atypical Appendix Positions:

Variations in the anatomical position of the appendix (e.g., retrocecal, pelvic) can obscure typical symptoms, necessitating a high index of suspicion and the use of advanced imaging techniques.

Summary of Diagnostic Strategies

A thorough, stepwise diagnostic approach that incorporates clinical evaluation, laboratory testing, and state-of-the-art imaging is essential for accurately identifying appendiceal conditions. This comprehensive assessment not only guides appropriate treatment but also helps prevent complications through early and precise diagnosis.

Therapeutic Strategies for Appendix Conditions

Management of appendiceal disorders requires a tailored approach based on the specific condition and its severity. Treatment options range from conservative, nonsurgical management to surgical intervention and even advanced therapies in complex cases. This section discusses current strategies for effectively treating appendiceal diseases.

Management of Acute Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis remains the most common appendiceal emergency. The standard treatment is surgical removal of the inflamed appendix.

- Surgical Appendectomy:

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy:

This minimally invasive procedure involves making small incisions through which a camera and instruments are inserted to remove the appendix. Advantages include less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery. - Open Appendectomy:

An open surgical approach is sometimes necessary, particularly in cases with complications such as perforation or when laparoscopic surgery is contraindicated. - Nonsurgical Treatment:

In selected cases of uncomplicated appendicitis, antibiotic therapy may be employed as a primary treatment. This approach requires careful patient selection and close monitoring for recurrence.

Treatment of Appendiceal Abscess

When appendicitis leads to the formation of an abscess, initial management often involves nonoperative measures.

- Antibiotic Therapy:

Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are administered to control the infection. - Percutaneous Drainage:

Under imaging guidance, drainage of the abscess may be performed to remove pus and reduce inflammation. - Interval Appendectomy:

Once the acute inflammation has subsided, a delayed (interval) appendectomy might be recommended to prevent recurrence, although this strategy is subject to clinical debate.

Therapeutic Approaches for Appendiceal Tumors

Appendiceal neoplasms require management strategies that depend on the tumor type, size, and spread.

- Surgical Resection:

- Appendectomy:

Small, benign tumors such as carcinoid tumors may be treated with a simple appendectomy. - Right Hemicolectomy:

For larger or malignant tumors, especially those with lymphatic involvement, a more extensive resection involving the right colon (right hemicolectomy) may be necessary. - Adjuvant Therapies:

In cases of malignant neoplasms, chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be considered postoperatively to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Management of Appendiceal Mucocele

A mucocele involves the accumulation of mucus within the appendix and can range from benign to potentially malignant conditions.

- Surgical Excision:

Complete removal of the appendix is essential to prevent rupture, which could lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei—a serious condition where mucinous material spreads throughout the abdomen. - Preventive Measures:

Careful surgical technique is required to avoid spillage of mucinous contents and to ensure thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity.

Overview of Advanced and Emerging Therapies

While traditional surgical and medical therapies remain the mainstay, emerging treatment modalities continue to evolve.

- Minimally Invasive Techniques:

Advances in laparoscopic and robotic surgery have improved surgical outcomes and reduced recovery times. - Targeted Molecular Therapies:

For malignant conditions, particularly appendiceal adenocarcinomas, targeted therapies that inhibit specific molecular pathways are under investigation. - Immunotherapy:

Experimental approaches involving immunomodulation and checkpoint inhibitors are being explored in cases of advanced malignancies.

Summary of Treatment Insights

A multi-pronged therapeutic strategy is essential for managing the diverse spectrum of appendiceal disorders. From prompt surgical intervention in acute appendicitis to carefully tailored treatments for tumors and mucoceles, modern management emphasizes individualized care, early diagnosis, and the integration of advanced surgical and medical therapies.

Nutritional and Supplementary Support for Appendix Wellness

Beyond conventional medical treatments, dietary choices and specific supplements may play a role in maintaining overall digestive health and possibly reducing the risk of appendiceal inflammation. This section reviews nutritional strategies and natural supplements that support gut health and immune function.

Essential Nutrients and Dietary Considerations

A diet rich in fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants supports the digestive system and may help prevent gastrointestinal complications.

- Fiber-Rich Foods:

Consuming ample fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes promotes regular bowel movements, reduces constipation, and may lower the risk of appendiceal blockage. - Antioxidant Vitamins:

Vitamins C and E are potent antioxidants that can help protect gut tissues from oxidative stress and inflammation. - Hydration:

Adequate water intake is crucial for proper digestion and for keeping the intestinal contents moving smoothly, thereby reducing the risk of fecal impaction.

Herbal Supplements and Natural Compounds

Certain herbal remedies have long been used to support gastrointestinal health and may offer benefits for the appendix.

- Ginger:

Renowned for its anti-inflammatory and digestive properties, ginger may help soothe gastrointestinal discomfort and enhance digestive function. - Turmeric (Curcumin):

Curcumin, the active compound in turmeric, exhibits strong anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects that can support gut health and reduce inflammatory responses. - Probiotics:

Probiotic supplements help maintain a balanced gut microbiome, which is critical for immune function and may assist in repopulating beneficial bacteria after gastrointestinal disturbances.

Antioxidants and Enzyme Support

Antioxidants and digestive enzymes play a crucial role in protecting the digestive tract from oxidative damage and ensuring efficient digestion.

- Green Tea Extract:

Rich in polyphenols, green tea extract provides antioxidant benefits that support overall gastrointestinal health. - Digestive Enzymes:

Supplements containing enzymes like protease, amylase, and lipase can enhance digestion and reduce the burden on the gastrointestinal system, potentially benefiting appendix health.

Integrating Dietary Strategies

- Balanced Diet Approach:

Focus on a diet that emphasizes whole, unprocessed foods, a variety of fruits and vegetables, and lean proteins. Such a diet provides essential nutrients while supporting gut motility and overall digestive health. - Regular Meal Timing:

Eating at consistent intervals helps regulate digestion and prevents the overaccumulation of fecal matter, reducing the likelihood of appendiceal obstruction. - Mindful Eating:

Practicing mindful eating can improve digestion and reduce stress, further contributing to a healthy digestive system.

Recap of Nutritional Support

Optimizing nutrition and incorporating targeted supplements can enhance gastrointestinal health and may play a preventive role in appendiceal disorders. These dietary strategies, when combined with proper hydration and a balanced lifestyle, create a robust foundation for maintaining overall digestive well-being.

Lifestyle Recommendations for Optimal Appendix Health

A proactive lifestyle is integral to maintaining not only general health but also the wellness of the digestive system, including the appendix. This section provides actionable recommendations to promote optimal appendiceal function and overall gut health.

Dietary and Hydration Practices

- High-Fiber Diet:

Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes to ensure regular bowel movements and prevent constipation. - Adequate Hydration:

Drinking sufficient water throughout the day aids in digestion, softens stools, and helps maintain a healthy intestinal environment. - Limit Processed Foods:

Reducing the intake of processed, high-fat, and low-fiber foods minimizes gastrointestinal irritation and inflammation.

Physical Activity and Gut Motility

- Regular Exercise:

Engaging in moderate physical activity such as walking, jogging, or cycling stimulates intestinal motility and promotes efficient digestion. - Core Strengthening:

Exercises that target the abdominal muscles can enhance overall digestive function and support proper gut motility.

Avoidance of Harmful Substances

- Smoking Cessation:

Quitting smoking is crucial, as tobacco use is linked to numerous gastrointestinal disorders, including inflammation and impaired immune function. - Moderation of Alcohol:

Limiting alcohol consumption helps reduce gastrointestinal irritation and supports overall digestive health.

Preventive Health Measures

- Regular Medical Check-Ups:

Routine health screenings and check-ups allow for early detection and management of potential appendiceal issues. - Vaccinations:

Staying current with vaccines, such as those for influenza and other infections, can indirectly benefit digestive health by reducing the overall burden of systemic inflammation. - Stress Management:

Chronic stress can negatively impact digestion. Techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, and yoga are effective in reducing stress and supporting gut health.

Monitoring and Early Intervention

- Symptom Awareness:

Pay close attention to changes in abdominal pain, bowel habits, or overall digestive comfort. Early medical consultation can prevent complications. - Hygiene and Food Safety:

Practicing good hygiene and adhering to safe food handling practices can reduce the risk of infections that may compromise gut health.

Summary of Lifestyle Guidelines

Implementing a holistic lifestyle that incorporates healthy dietary habits, regular exercise, stress management, and preventive healthcare is essential for maintaining optimal appendix and digestive health. These proactive strategies help create a resilient gastrointestinal system capable of adapting to internal and external challenges.

Authoritative Resources for Digestive Health

Reliable, up-to-date resources are invaluable for both healthcare professionals and individuals seeking to understand and maintain digestive health. The following sources provide comprehensive insights into appendiceal and gastrointestinal wellness.

Recommended Books

- “Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ” by Giulia Enders:

This engaging and informative book explores the complexities of the digestive system, including the role of the appendix, in an accessible manner. - “The Good Gut: Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health” by Justin Sonnenburg and Erica Sonnenburg:

Focusing on the gut microbiome, this book delves into how a balanced intestinal ecosystem supports overall health. - “Fiber Fueled: The Plant-Based Gut Health Program” by Will Bulsiewicz:

This resource emphasizes the importance of dietary fiber in maintaining gut health and preventing digestive disorders.

Academic Journals

- Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology:

A peer-reviewed publication that features cutting-edge research on digestive diseases, including studies on the immune functions of the appendix. - Gut:

Recognized as one of the leading journals in gastroenterology, it covers a wide range of topics related to digestive health, microbiome research, and clinical practices.

Mobile Applications

- MyFitnessPal:

A comprehensive app that tracks nutrition and exercise, helping users maintain a balanced diet that supports digestive health. - Cara Care:

This app is designed for managing digestive conditions, offering personalized insights and symptom tracking to optimize gut wellness. - Fooducate:

Fooducate assists users in making healthier food choices by providing detailed nutritional information and personalized dietary recommendations.

Recap of Resource Value

These authoritative resources offer extensive knowledge, from detailed research articles to user-friendly mobile applications, empowering individuals and professionals to make informed decisions regarding digestive and appendiceal health.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of the appendix?

The appendix is believed to contribute to immune function and act as a reservoir for beneficial gut bacteria, supporting the reestablishment of the intestinal microbiome after gastrointestinal disturbances.

How does the appendix aid in immune response?

Rich in lymphoid follicles, the appendix may help stimulate the production of antibodies and promote the maturation of immune cells, thus contributing to gut-associated immunity.

What are the common symptoms of appendicitis?

Appendicitis typically presents with pain that begins around the navel and later localizes to the lower right quadrant, accompanied by nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and sometimes fever.

Which imaging techniques are used to diagnose appendicitis?

Ultrasound, CT scans, and sometimes MRI are used to diagnose appendicitis by visualizing an enlarged, inflamed appendix and detecting any complications such as abscesses.

How can a high-fiber diet benefit the appendix?

A fiber-rich diet promotes regular bowel movements, reducing the risk of fecal impaction and luminal obstruction, which can contribute to appendicitis and other gastrointestinal disorders.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized guidance and treatment options.

We encourage you to share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your favorite social media platform to help spread awareness about digestive health and the potential importance of the appendix!