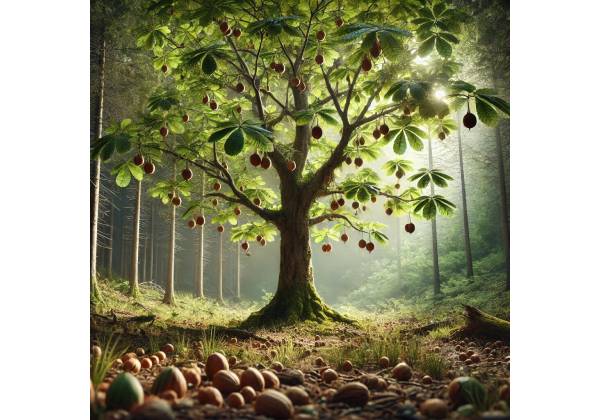

Butternut (Juglans cinerea), also known as White Walnut, is a lesser-known tree in the walnut family that grows primarily in parts of North America. Despite being overshadowed by its more famous relatives (like the black walnut), Butternut holds its own unique place in ecological systems and in certain historical herbal practices. People once cherished it for its light-colored, oily nuts as well as the potential medicinal attributes found in its bark and inner wood. You might spot a Butternut tree by its distinctive leaves and elongated, oval-shaped nuts that develop a sticky, fuzzy coating as they ripen. Over the centuries, the tree’s bark and fruit gained a small but steady reputation in folk traditions, particularly for digestive support and as a mild laxative.

Butternut’s population has faced challenges from a fungal disease called Butternut Canker, making mature trees harder to find in some regions. Yet conservationists and horticultural enthusiasts still champion the species for its ecological value—contributing nut mast for wildlife and genetic diversity among walnut trees. For those intrigued by heritage remedies or searching for a distinctive tree to cultivate, Butternut offers a mix of historical lore, subtle practical uses, and an understated presence in North American woodlands.

Here are a few of the main benefits and features often linked to Butternut:

- Historically recognized as a gentle laxative or cathartic

- Provides nutrient-rich nuts prized by wildlife (and occasionally for human consumption)

- Contributes to biodiversity in hardwood forests across the eastern United States and Canada

- Used in certain old herbal traditions for potential liver and digestive support

- Offers an attractive, slow-growing option for landscapes or woodlots

Table of Contents

- Botanical Profile and Identification of Butternut

- Butternut’s Historical Footprint and Legacy

- Phytochemistry and Active Constituents in Butternut

- Potential Health Benefits Attributed to Butternut

- Defining Properties That Give Butternut Its Character

- Common Uses and Safety Considerations Around Butternut

- Noteworthy Scientific Research and Significant Studies on Butternut

- Butternut FAQ

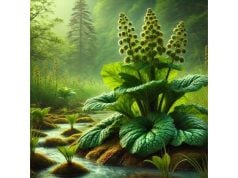

Botanical Profile and Identification of Butternut

Butternut (Juglans cinerea) is part of the Juglandaceae family, which also includes black walnut (Juglans nigra) and the widely cultivated English walnut (Juglans regia). While it shares some family traits—like producing edible nuts—it stands apart with specific characteristics, from its leaf structure to the hue and texture of its bark.

Physical Characteristics

- Leaves

- Butternut leaves are pinnately compound, typically with 11 to 17 leaflets that are sharply serrated. They often measure between 15 to 25 inches long in total.

- Each leaflet tends to be somewhat oblong and a bit fuzzy on the underside, especially when young.

- Bark and Trunk

- The bark ranges from light gray to a somewhat silvery shade, often featuring deep furrows or ridges. Young trees might have a smoother bark that gradually becomes more textured over the years.

- With time, the trunk can grow to 1–2 feet in diameter, though Butternut trees are often smaller and more short-lived than black walnuts.

- Nuts

- Butternut nuts develop in small, sticky, husk-like coverings that appear greenish and oblong. Inside is a hard, bumpy shell that encloses a sweet kernel reminiscent of walnut flavor, though smaller and more irregular in shape.

- Animals like squirrels, chipmunks, and birds typically relish these nuts—humans can enjoy them too, though collecting and shelling them can be time-consuming.

- Flowers

- As a monoecious species, Butternut produces separate male and female flowers on the same tree. The male catkins appear as greenish, drooping clusters, while female flowers bloom near the twig tips.

Native Range and Habitat

- Geographical Spread

Butternut is found mainly in the eastern United States and parts of Canada, from New England and the Great Lakes region to areas in the South, though less frequent there. - Soil Preferences

It prefers well-drained, fertile soils, often in mixed hardwood forests, ravines, or rich slopes. Like other walnuts, it can release juglone into the soil, affecting the growth of certain plants nearby.

Differentiating from Other Walnuts

- Juglans nigra (Black Walnut)

- Black walnut has darker, more corrugated bark, and the nuts have a stronger flavor. Butternut’s bark is paler, and its nuts produce an oil considered milder or sweeter.

- Leaflet Count

- Butternut usually has fewer leaflets (under 19) compared to black walnut, whose compound leaves might hold up to 23 leaflets.

Conservation Status

- Butternut Canker

A fungal disease has devastated Butternut populations in many areas, leading to concerns about the tree’s future. Conservation efforts include breeding resistant trees and establishing protective measures. - Value in Forestry

Though not as commercially prized as black walnut for wood, Butternut still has appeal for specialty woodworking or smaller-scale projects. The real emphasis now is on preserving existing wild stands.

By keeping an eye on the bark color, the distinct shape and fuzziness of the leaves, and the oblong, sticky-husked nuts, you’ll be able to spot Butternut among forest companions. Whether you find it in a wooded ravine or your backyard orchard, it’s a unique presence that signals an essential piece of North America’s natural tapestry.

Butternut’s Historical Footprint and Legacy

While Butternut might not hold the same ubiquitous recognition as black walnut, it still carries a layered past—rooted in early American frontier life, indigenous applications, and even Civil War references. Over the centuries, people have tapped its nuts, bark, and sap for various tasks, forging a heritage that merges culinary curiosity with occasional medicinal usage.

Indigenous and Early Colonial Times

- Native American Roots

- Some indigenous tribes recognized Butternut’s potential for mild laxative or cleansing uses. The bark or inner cambium might have been integrated into teas or decoctions to address minor digestive or liver ailments.

- The nuts, while less abundant than some other nuts, were occasionally collected for eating or pressed for oil. However, other tree nuts often overshadowed them in popularity.

- European Settlement

- With colonial expansion, settlers noticed that Butternut offered a smaller, sweeter nut that could be used in baking or for nut oil.

- The bark’s mild medicinal role in “tonics” or “physicks” also earned it a spot in some colonial-era home remedies, especially for gastrointestinal concerns.

Civil War Associations

- Butternut Clothing

Confusingly, “Butternut” became a nickname for Confederate soldiers during the American Civil War because their homespun uniforms often took on a brownish hue reminiscent of the stained color from butternut bark or walnut hull dyes. - Dye Usage

Indeed, at times, butternut bark could be used to create natural brown dyes, though black walnut was often more common for strong coloring.

Modern Conservation Outlook

- Decline from Canker

- By the late 20th century, Butternut canker had spread widely, drastically reducing healthy populations. This disease, caused by a fungal pathogen, can girdle the trunk and eventually kill the tree.

- Conservationists worry that without resistant cultivars or management strategies, Butternut’s presence in North American forests will keep shrinking.

- Orchard and Breeding Efforts

- Scientists and arborists have been collecting seeds from trees showing some tolerance to the fungus, hoping to create genetically robust lines.

- Private landowners sometimes cultivate Butternut for personal enjoyment—partly to maintain a living piece of regional heritage and wildlife support.

Cultural and Folk Reverence

- Regional Pride

In certain states where Butternut used to flourish, older residents recall how these trees provided occasional treats in the form of nuts or a mild remedy. This fosters a sense of local nostalgia. - Handcrafted Wood Items

Butternut’s wood, though softer than black walnut, still has a pleasing grain. Some craftsmen value it for small furniture pieces, carvings, or interior paneling, linking the tree to a sense of artisanal tradition.

All told, while Butternut might not command the same historical dominance as, say, sugar maple or hickory, it still contributed to local diets, herbal practices, and cultural identity in pockets of North America. Ongoing interest in reintroducing or preserving Butternut underscores how heritage trees can remain relevant even in changing landscapes—protecting biodiversity and reminding us of the region’s ecological and cultural depth.

Phytochemistry and Active Constituents in Butternut

Butternut, akin to its walnut relatives, carries a range of chemical compounds in its bark, leaves, and nuts that define both its potential benefits and its cautionary aspects. Traditional references mention the bark’s gentle laxative properties, pointing to certain compounds that can act on the digestive system. Let’s explore what modern insights say about these possible active elements.

1. Juglone and Related Naphthoquinones

- Allelopathic Compound

Like black walnut, Butternut produces juglone—a naphthoquinone known to inhibit growth of some neighboring plants. Juglone is found in bark, roots, and to a lesser degree, leaves, which is why many plants fail to thrive near walnut trees. - Mild Toxic or Irritant

In large concentrations, juglone can be toxic or irritating. This property helps Butternut outcompete certain vegetation in the wild but also means caution is advised for those hoping to use bark or leaves in herbal teas without a good understanding of dosage.

2. Tannins and Phenolic Acids

- Astringent Effects

Tannins, present in bark or unripe nuts, can lend an astringent property that in mild doses might help tone tissues or quell minor digestive distress. If overused, it can irritate the GI tract. - Phenolic Variation

Traces of gallic acid or ellagic acid might also appear—these polyphenols can have antioxidant or mild anti-inflammatory actions in lab studies, though real-world usage remains under-studied.

3. Fatty Acids in Nuts

- Nut Oil Composition

Butternut kernels, while not as large or oily as black walnuts, do house beneficial fatty acids (like linoleic or oleic). People occasionally used them in old-fashioned recipes or pressed them for small-scale oil production. - Taste Profile

The nuts’ flavor can be sweet and somewhat buttery, aligning with their name. However, the time-intensive shelling process discourages commercial scale usage.

4. Glycosides and Mild Laxative Components

- Potential Cathartic Elements

Historical references label butternut bark as containing glycosides or resinous substances that gently stimulate the bowel. This might be somewhat akin to other laxative shrubs or barks, though butternut’s effect is typically described as milder. - Specific Identification

Modern analysis is limited; there’s no large-scale commercial impetus to thoroughly map every compound, so we rely on old pharmacopeial notes and smaller scientific papers.

5. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Hints

- Bioactive Flavonoids

Although not heavily documented, we can infer that certain flavonoids appear in the leaves or bark, providing modest radical-scavenging abilities. - Comparison with Other Walnuts

Studies on black walnut or English walnut highlight robust polyphenolic profiles. Butternut likely shares some parallels but may differ in total content or ratio. Without dedicated research, it’s speculation.

6. Variation Due to Environment

- Soil and Climate Influence

The chemical makeup can shift with differences in soil acidity, moisture, or climate stress. Trees in harsh conditions might produce more protective compounds. - Seasonal Changes

The bark or leaf chemical levels could vary from spring growth to autumn senescence, affecting potential potency if used as an herbal resource.

All in all, the partial data we have suggests that butternut’s bark or root can contain mild laxative glycosides, astringent tannins, and certain naphthoquinones like juglone that provide some competitive advantage in nature. While these features might yield small benefits in a carefully controlled herbal context, they also emphasize why butternut’s raw usage is approached with caution. Coupled with the eco-friendly note that juglone might hamper surrounding flora, it’s clear that what works for the tree’s survival could require thoughtful application in any medicinal or horticultural scenario.

Potential Health Benefits Attributed to Butternut

Although Butternut’s not a big name in modern herbal medicine, a few recognized folk uses have persisted through the generations. Some revolve around GI support, while others hint at mild immune or hepatic roles. Let’s explore these traditions—while noting that large-scale clinical validation is scarce.

1. Gentle Laxative or Cathartic

- Historical “Cathartic” Tag

Butternut bark was often described as a gentle cathartic, meaning it could stimulate the bowels without as harsh an effect as stronger laxatives. In 19th-century American herbal texts, it was recommended for occasional constipation or “sluggish intestines.” - Dosing and Preparations

Typically, small amounts of the dried bark or an extract were used. People believed it encouraged a healthy GI flow without causing severe cramping. Overuse, however, could trigger more forceful diarrhea.

2. Liver and Gallbladder Support

- Folklore

Certain references mention butternut root or bark as “cleansing,” sometimes used in mild “spring tonics” aimed at supporting hepatic or gallbladder function. This usage was more anecdotal, lacking strong documentation. - Modern Perspective

Because robust studies are lacking, any direct effect on the liver is speculative. Still, some herbal compendiums maintain that small doses in short-term use can complement a balanced diet if you want a mild “detox” approach.

3. Potential Anti-Parasitic or Anti-Inflammatory Angles

- Old Veterinary Use

In some rural contexts, farmers used butternut-based brews for livestock as a mild vermifuge or to keep digestive issues in check. However, it’s overshadowed by more recognized anti-parasitic herbs. - Inflammation

Tannins and certain naphthoquinones might reduce mild inflammation if used topically or internally, but these claims remain mostly anecdotal in the absence of thorough research.

4. General Tonic or Immune-Boosting

- Influence of Traditional Tonics

The idea that a gentle herb can “support overall vitality” is commonplace in older texts, though the specifics for Butternut are minimal. Because the bark can have a mild stimulant effect on excretory processes, some believed it had broader immune or circulatory ramifications. - No Substantial Modern Trials

Without confirmatory trials, any statement about immune enhancement is more folkloric than evidence-based.

5. Culinary Nut Use

- Nutritious Kernel

The sweet, buttery nut was sometimes featured in pioneer cooking or confections. The notion that it’s beneficial for health parallels how all tree nuts can offer healthy fats, proteins, and micronutrients. - Limited Commercial Availability

Harvesting and shelling Butternut nuts is labor-intensive, so they never took off in the market. But in small homestead or local contexts, they can provide a natural, nutrient-dense snack.

6. Balanced View of Efficacy

- Small Effects, Possibly

The anecdotal evidence suggests that Butternut might be valuable in short spurts—for example, a mild GI push or a gentle “seasonal cleanse.” However, no one should see it as a cure-all. - Compatibility

Combining Butternut bark with other recognized GI-supportive herbs (like peppermint or ginger) could yield synergy, though that’s purely an old folk approach. Real caution about potential toxicity or strong side effects remains necessary.

In essence, the rumored or historically cited benefits revolve around mild bowel regulation, potential minor hepatic or “detox” support, and the notion of an overall “cleansing” effect. People with an interest in older American herbal traditions might explore this carefully—but it’s best approached with modern caution, acknowledging limited research and the potential for negative effects if misused.

Defining Properties That Give Butternut Its Character

Butternut’s identity stretches beyond a simple “walnut alternative.” From an ecological vantage point, it’s recognized for its place in forest biodiversity. Aesthetically, it’s a modestly sized hardwood that can yield sweet nuts and lovely, light-hued wood. Here are the defining attributes that shape Butternut’s distinct place in nature and culture.

1. Pale, Mottled Bark and Elegant Form

- Light Gray Tone

The trunk’s bark typically stands out among darker forest neighbors, with shallow furrows and a silvery to pale gray color. - Branch Structure

The branching pattern can appear somewhat wide-spreading, giving the tree a relaxed canopy. At full maturity (which is rarer now due to disease), it can reach 60 feet or so in height.

2. Sticky Green Husk and Sweet Nut

- Elongated Husk

Each Butternut husk is longer and more oblong than a typical round walnut husk, covered in sticky, fuzzy bristles that cling to your fingers if you handle them fresh. - Kernel Flavor

Tastes range from buttery to mildly sweet, reminiscent of a soft version of walnut. But they’re often smaller or more irregular, making commercial harvest less practical.

3. Juglone Influence in Soil

- Allelopathy

Like black walnut, Butternut can release juglone into the soil, inhibiting certain plants. Gardeners must plan accordingly if planting near Butternut, as susceptible species (like tomatoes or certain ornamentals) may fail or grow poorly. - Ecosystem Niche

Some plants adapt to or tolerate juglone, so the presence of Butternut can shape a unique micro-ecosystem beneath its canopy.

4. Wood Qualities

- Butternut Lumber

Woodworkers sometimes appreciate the soft, pale wood that’s easy to carve. The color is typically lighter than black walnut, with a warm, cream-to-tan hue and subtle grain patterns. - Limited Supply

Because of the canker issue and the species’ reduced presence, Butternut lumber is often scarce or reclaimed from fallen or diseased trees.

5. Old-Fashioned “Butternut Brown” Dye

- Husk or Bark

The husks can produce a yellowish-brown stain, historically used as a natural colorant for fabrics or even as a paint or stain. Confederate soldiers’ uniforms’ “butternut color” references this tradition. - Fading Over Time

Like many natural dyes, it can lighten after repeated washings or sun exposure if used on textiles.

6. Wildlife and Nut Forage

- Squirrels and Birds

The sweet nuts are a draw for woodland creatures, ensuring seeds might be scattered or partially buried, leading to natural regeneration. - Biodiversity Boost

Even though populations are diminishing, each Butternut tree that survives fosters a microhabitat, from cavities in mature trunks to the seasonal nut crop.

7. Slow Growth and Short Lifespan

- Comparative Limitations

While black walnut can achieve longevity in centuries, Butternut is known to live fewer decades, especially in modern times with disease pressures. This influences how foresters weigh it for reforestation or orchard planning. - Taproot Depth

The robust root system anchors the tree in well-drained soils, though it also complicates transplanting older saplings.

Summarizing these traits highlights how Butternut merges gentle orchard potential (with sweet nuts) with modest herbal references (like mild digestive usage) and a unique presence in local forests. While overshadowed by more common walnuts, the species’ distinct bark, nut shape, and ecological contributions preserve its identity as a noteworthy North American hardwood.

Common Uses and Safety Considerations Around Butternut

For most people, Butternut’s practical uses revolve around smaller-scale enjoyment—maybe the occasional nut harvest, a dabble in old-time folk remedies, or simply appreciating it as a backyard or forest tree. However, it’s wise to keep in mind a few guidelines if you want to dabble in horticulture or the more experimental side of herbal usage.

1. Horticultural and Landscape Uses

- Yard or Orchard Planting

- If you have space and well-drained soil, adding a Butternut tree can bring shade, wildlife interest, and potential future nut harvests. Just be mindful of juglone’s effect on nearby plants.

- Because of disease vulnerability, consider seeking disease-tolerant Butternut hybrids or cultivars if available in local nurseries.

- Reforestation or Conservation Projects

- Some landowners volunteer with organizations that try to reintroduce or protect Butternut in forest stands. You might plant saplings in carefully chosen spots to bolster local biodiversity.

- Regular monitoring for signs of canker is crucial. Removing heavily infected branches early can slow disease spread.

2. Nut Harvesting

- Collecting the Husked Fruit

Nuts typically drop in late summer to early fall. The greenish, sticky husks can be peeled away (wear gloves to avoid stain and sticky residue). Then the kernel inside the hard shell is extracted—a labor-intensive process. - Culinary Use

If you do gather enough, you can roast or chop them for baked goods. The flavor can be a mild treat, though you rarely see them sold in typical grocery stores due to the husking difficulty.

3. Historical or Folk Herbal Usage

- Mild Laxative or Digestive Aid

- Small amounts of dried bark or “Butternut bark extract” historically functioned as a gentle cathartic. Modern usage is rare and overshadowed by well-researched alternatives.

- Possible Side Effects

- Overdosing can cause diarrhea, vomiting, or potential toxicity from glycosides. If one is keen to replicate old remedies, it’s best to consult a seasoned herbalist or find safer known GI-friendly herbs (like senna or cascara) which are standardized.

4. Woodcraft and Dye

- Woodworking

Carvers appreciate the softness of Butternut wood, sometimes calling it “White Walnut.” For small projects like boxes, panels, or carvings, it can yield a pleasing finish if protected properly. - Natural Dye

Soaking or boiling husks in water produces a brownish dye. While colorfastness might be moderate at best, hobbyists find it fun for small craft or fabric experiments.

5. Potential Cautions

- Juglone Toxicity

- Avoid planting sensitive veggies (like tomatoes, peppers, or certain ornamental plants) too close to Butternut. Juglone in the soil can stunt or kill them.

- Ingestion Risks

- The bark’s strong chemicals can be harmful if used improperly. While mild amounts might be historically recognized as safe, the margin for error can be small.

- Allergies

- People allergic to walnuts or tree nuts in general might find Butternut nuts or even touching the husks triggers a reaction. Testing a small contact is wise.

6. Children and Pets

- Keep Ingestion Minimal

While small accidental nibbles of the outer husk or leaves are unlikely to be lethal, the presence of glycosides means it’s prudent to discourage children or pets from chewing on any part. - Nut Choking Hazard

If the nuts are lying around, remember they’re quite hard. That can present a choking risk for very young children or smaller animals if they try to crack them.

7. Pairing with Other Approaches

- Supplement Synergy

If exploring Butternut bark for GI support, folks sometimes combine it with gentler herbs like peppermint or chamomile to mask bitterness or moderate any harshness. However, formal synergy data are minimal. - Monarch and Pollinator Allies

If the tree is in a broader pollinator garden context, consider including local wildflowers that aren’t juglone-sensitive, ensuring you maintain a beneficial habitat for insects and birds.

In short, Butternut’s uses revolve around its mild, sweet nuts, potential for small-scale herbal references, and a strong presence in local landscapes. Where safety is concerned, the biggest watchouts are properly managing juglone effects on neighboring plants, using bark only with caution, and staying mindful of the real risk that overconsumption or misapplication can do more harm than good. For many, simply enjoying the tree for its ecological and aesthetic virtues is enough—and a far safer approach.

Noteworthy Scientific Research and Significant Studies on Butternut

Butternut’s place in academia is relatively niche. Still, some investigations, especially in forestry or plant pathology, shed light on crucial aspects of its biology, challenges, and minor medicinal potential. Here are the main highlights:

1. Butternut Canker Research

- Fungal Pathogen Characterization

A pivotal set of studies in the Canadian Journal of Forest Research during the early 2000s pinned down Ophiognomonia clavigignenti-juglandacearum (formerly Sirococcus clavigignenti-juglandacearum) as the cause of canker. These works documented the fungus’s life cycle and how it infects Butternut bark and cambium. - Conservation Genetics

Follow-up research explored genetic diversity in Butternut populations, aiming to identify trees showing natural resistance. A 2015 paper in Forest Ecology and Management recommended selective breeding strategies.

2. Ethnobotanical and Herbal References

- 19th-Century Herbal Texts

Historical reevaluations of old pharmacopeias, such as the 1860s–1880s American Eclectic volumes, confirm that Butternut bark was indeed recommended for mild laxative use. Modern meta-analyses note the lack of contemporary human trials but validate that it was recognized in that era. - Cathartic Compound Identification

Limited lab analyses from the mid-20th century (like a small 1962 Planta Medica note) isolated some anthraquinone-like substances, though not thoroughly confirming them. The consensus was that bark extracts carried “mild purgative qualities.”

3. Juglone Effects

- Allelopathy and Growth Studies

Several horticultural or agricultural bulletins, such as a 1980 article in HortScience, tested the effect of juglone from Butternut on tomato or other commonly sensitive species. Results were consistent: stunted growth or chlorosis, underscoring the plant’s allelopathic impact. - Comparisons with Black Walnut

Black walnut typically shows higher juglone concentrations, but Butternut still exhibits enough to hamper certain plant neighbors.

4. Wood Quality and Carving Potential

- Timber Analysis

A 1978 USDA study on lesser-known hardwoods described Butternut’s wood as “light, moderately soft, easily worked, and dimensionally stable,” awarding it decent marks for carving or paneling. - Sawing and Kiln Drying

Because the species is rarer, more specialized sawmills handle it. Some research in small-scale pilot projects found no unusual complexities beyond typical walnut drying protocols.

Butternut FAQ

Is Butternut the same as Butternut Squash?

No, they’re different. Butternut Squash is a type of winter squash (Cucurbita moschata), while Butternut here refers to the tree species (Juglans cinerea). The only similarity is the shared name, which can lead to confusion, but the plant family, usage, and form are entirely different.

Can I safely eat Butternut nuts?

Yes, with care. The nuts taste sweet and somewhat buttery. However, they can be tedious to shell, and the sticky husks can stain your hands. Also, ensure you correctly identify the tree and avoid nuts that appear moldy or compromised. As with all foraged foods, proceed cautiously if you have nut allergies.

How do I plant a Butternut sapling?

Choose a location with well-drained soil and full to partial sun. Dig a deep hole for the taproot, and space it away from other plants that might be juglone-sensitive (like tomatoes). Water it regularly for the first year, but be mindful not to over-saturate. Once established, it’s fairly low-maintenance.

Does Butternut bark really work as a mild laxative?

Historically, it was used as “pleurisy root” or a gentle cathartic, but it’s not commonly employed today. Overconsumption can lead to excessive purging or toxicity from certain compounds. If you’re considering it for GI support, consult a qualified health professional first. Safer, well-studied herbal laxatives exist on the market.

Disclaimer

This article is offered for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice. If you’re contemplating using Butternut (Juglans cinerea) for health reasons, especially in the form of bark or raw plant materials, please seek guidance from a qualified healthcare professional.

If you found this overview of Butternut’s background, properties, and potential uses interesting, feel free to share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your favorite social platform. Spreading knowledge about less-common native species can help preserve them—and might inspire others to learn more about our rich botanical heritage!