Uveal Effusion Syndrome (UES) is a rare and complicated ocular condition characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the uveal tract, which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. This fluid buildup causes uveal tissue detachment, particularly of the choroid, which can result in significant visual impairment if not properly diagnosed and managed. The exact cause of UES is unknown, but it is thought to be related to abnormalities in the structure of the sclera, the eye’s outer layer, as well as problems with venous outflow or the permeability of the blood-ocular barrier.

Structure of the Uveal Tract and Sclera

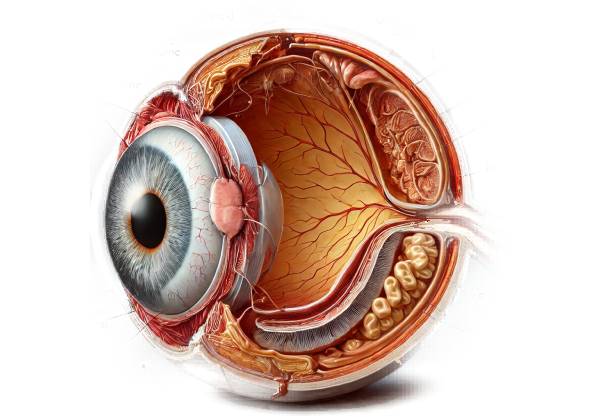

To understand Uveal Effusion Syndrome, you must first understand the anatomy of the uveal tract and its relationship to the sclera. The uveal tract is the eye’s middle vascular layer, which is responsible for nourishing the eye and maintaining its internal environment. It has three major parts:

- Iris: The iris is the colored part of the eye that regulates the amount of light entering the eye by changing the size of the pupil.

- Ciliary Body: The ciliary body produces aqueous humor, the fluid that fills the anterior chamber of the eye, and controls the shape of the lens, which aids focusing.

- Choroid: The choroid is a dense network of blood vessels that connects the retina and the sclera and provides oxygen and nutrients to the retina’s outer layers.

In contrast, the sclera is the eye’s tough, fibrous outer layer, which provides structural support and protection. It is continuous with the cornea at the front of the eye and surrounds the entire globe.

Pathophysiology Of Uveal Effusion Syndrome

The pathophysiology of Uveal Effusion Syndrome is characterized by abnormal fluid accumulation in the uveal tract, specifically in the choroid. This fluid buildup can cause choroidal detachment, retinal detachment, and a number of other complications that can impair vision.

- Scleral Abnormalities: One of the primary factors thought to contribute to UES is an abnormality in the structure of the sclera. In many cases of UES, the sclera thickens or has low collagen content, obstructing the normal flow of fluid out of the uveal tract. This abnormality can cause a bottleneck effect, accumulating fluid within the choroid and leading to detachment.

- Impaired Venous Outflow: Impaired venous outflow is another risk factor for UES. The venous drainage of the uveal tract is primarily via the vortex veins, which exit through the sclera. If the venous outflow becomes obstructed or compromised, pressure within the uveal tract rises and fluid accumulates.

- Increased Permeability of the Blood-Ocular Barrier: The blood-ocular barrier regulates the movement of substances between the blood and the ocular tissues, ensuring the integrity of the eye’s internal environment. In UES, the barrier may be more permeable, allowing fluid to leak into the uveal tract and contribute to effusion.

Clinical Features of Uveal Effusion Syndrome

The clinical presentation of Uveal Effusion Syndrome varies according to the severity of the condition and the extent of fluid accumulation. However, several key symptoms and signs are frequently associated with this condition.

- Decreased Visual Acuity: One of the most common symptoms of UES is a gradual or abrupt decrease in visual acuity. This can happen when the retina or choroid detach, disrupting normal visual information processing. Patients may experience blurred vision, visual distortion, or even complete vision loss in severe cases.

- Vitreous Floaters: Another common UES symptom is vitreous floaters. These are small, dark spots or threads that seem to float across the field of vision. Floaters form when the vitreous humor, the gel-like substance that fills the eye, becomes displaced or disturbed as a result of the underlying choroidal detachment.

- Peripheral Visual Field Defects: As the choroidal or retinal detachment progresses, patients may experience problems with their peripheral vision. These defects, known as “shadows” or “curtains,” encroach on the periphery of the visual field and may indicate that the detachment is progressing.

- Increased Intraocular Pressure (IOP): In some cases, UES causes an increase in intraocular pressure. This is especially true if the effusion causes secondary angle-closure glaucoma, in which the fluid accumulation pushes the iris forward, blocking the drainage angle and causing an increase in pressure. Increased IOP can lead to additional complications, such as optic nerve damage, if not treated promptly.

- Choroidal Folds: Choroidal folds are a common feature in UES. Ridges or wrinkles in the choroid result from underlying detachment and fluid accumulation. A dilated fundoscopic examination may reveal choroidal folds, which can cause visual distortion.

- Macular Edema: Macular edema, or swelling of the macula (the central part of the retina responsible for detailed vision), can develop in UES. Fluid leakage into the macula causes swelling, resulting in blurring and distortion of central vision. Macular edema is a severe complication that can impair visual acuity.

- Retinal Detachment: In more advanced cases of UES, fluid accumulation can cause the retina to lift or pull away from its normal position, resulting in a retinal detachment. Retinal detachment is a medical emergency that requires immediate attention to avoid permanent vision loss.

Subtypes Of Uveal Effusion Syndrome

UES can be divided into subtypes based on its underlying cause and presentation. The classification of UES contributes to the diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

- Idiopathic Uveal Effusion Syndrome: This subtype of UES has no identifiable underlying cause. Patients with idiopathic UES typically exhibit the syndrome’s classic symptoms, such as decreased visual acuity, choroidal detachment, and retinal detachment. The sclera may appear thickened, but no other systemic or ocular conditions are present.

- Secondary Uveal Effusion Syndrome: Secondary UES results from another underlying condition, such as inflammation, trauma, or a systemic disease that affects the uveal tract or sclera. Scleritis, uveitis, and sarcoidosis are all potential causes of secondary UES. In these cases, controlling the effusion requires effective management of the underlying condition.

- Nanophthalmic Uveal Effusion Syndrome: Nanophthalmia is a rare congenital condition defined by abnormally small eyes. Patients with nanophthalmia are more likely to develop UES due to structural abnormalities in the sclera and restricted space within the eye, which can impede normal fluid drainage.

Risk Factors and Epidemiology

Uveal Effusion Syndrome is a rare condition with an unknown prevalence. Several risk factors have been identified, which may increase the likelihood of developing UES.

- Age and Gender: Although UES can occur at any age, it is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged adults. There does not appear to be a significant gender bias, with males and females equally affected.

- Genetic Factors: Genetic factors may play a role in the development of UES, especially in nanophthalmic UES. There have been reports of familial cases of nanophthalmia, indicating that the condition has a hereditary component.

Key Diagnostic Methods for Uveal Effusion

Clinical Evaluation

- Comprehensive Eye Examination: The initial step in diagnosing Uveal Effusion Syndrome (UES) is to conduct a comprehensive eye examination. This examination consists of visual acuity testing to determine the extent of vision loss, slit-lamp biomicroscopy to evaluate the anterior segment of the eye, and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement to detect any increase in pressure that could indicate secondary glaucoma. During this examination, the clinician will look for signs of choroidal and retinal detachment, as well as other structural abnormalities that could indicate UES.

- Fundoscopic Examination: A thorough examination of the fundus (the back of the eye) via direct or indirect ophthalmoscopy is required to diagnose UES. The clinician will examine the retina, optic disc, and choroid for evidence of detachment, choroidal folds, or retinal abnormalities. The presence of choroidal effusion, which appears as an elevated area of the choroid, is a significant finding in UES. The retinal detachment associated with UES frequently appears as a serous detachment, with no retinal tear or hole.

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM): UBM is a high-frequency ultrasound imaging technique that can produce detailed images of the anterior segment and ciliary body. In cases of UES, UBM can detect choroidal effusion, thickened sclera, and any abnormalities in the ciliary body that may be contributing to fluid accumulation. UBM is especially useful for determining sclera thickness and the presence of abnormal scleral or ciliary structures.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) is a non-invasive imaging technique that generates cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid. OCT can detect subtle changes in the retina, such as serous retinal detachment and macular edema, which are both associated with UES. OCT can also be used to assess choroidal thickness, which is often increased in UES, as well as to monitor disease progression and treatment response.

- Fluorescein Angiography (FA) is a procedure that involves injecting fluorescein dye into the bloodstream and then imaging the retinal and choroidal vasculature serially. FA in UES can reveal areas of delayed choroidal filling, dye leakage from choroidal vessels, and dye pooling in the subretinal space, all of which indicate choroidal detachment and retinal involvement. FA is particularly effective at distinguishing UES from other causes of choroidal and retinal detachment.

- Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA): ICGA is an imaging technique similar to FA that uses indocyanine green dye to better visualize the choroidal circulation. ICGA is especially useful for detecting choroidal vascular abnormalities and distinguishing UES from other choroidal pathologies like central serous chorioretinopathy and choroidal tumors. ICGA can provide detailed images of the choroidal vessels as well as any UES-specific leakage or pooling.

Additional Diagnostic Tests

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): In some cases, an MRI of the orbit may be used to evaluate the sclera, choroid, and other orbital structures. MRI can produce detailed images of the eye’s soft tissues, assisting in the identification of structural abnormalities, such as thickened sclera, that contribute to the development of UES. MRI can also help rule out other orbital or systemic conditions that cause similar symptoms.

- Systemic Evaluation: Because UES can be associated with systemic conditions like scleritis, rheumatoid arthritis, or sarcoidosis, a comprehensive systemic evaluation may be required. This may include blood tests to check for inflammation markers (such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] and C-reactive protein [CRP]), autoimmune markers (such as antinuclear antibodies [ANA]), and imaging studies of other parts of the body to detect systemic involvement.

- Genetic Testing: In cases of nanophthalmic UES, genetic testing may be considered to identify any underlying genetic mutations associated with nanophthalmia. This is especially useful in familial cases where several members have similar ocular abnormalities.

Treatment Strategies for Uveal Effusion Syndrome

The management of Uveal Effusion Syndrome (UES) is multifaceted and depends on the underlying cause, the severity of the condition, and the specific manifestations in each patient. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce fluid accumulation in the uveal tract, reattach detached uveal and retinal tissues, and maintain or restore vision. The treatment options range from conservative medical management to more invasive surgical procedures.

Medical Management

- Corticosteroids: In cases where inflammation is a factor in the development of UES, corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce inflammation and fluid accumulation. Corticosteroids can be given orally or intravenously, or locally (as topical eye drops or periocular injections). The choice of route is determined by the severity of the inflammation and the specific structures involved. Corticosteroids, on the other hand, are generally more effective in secondary UES, where an inflammatory or autoimmune condition is to blame.

- Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: Medications like acetazolamide can help lower intraocular pressure and fluid production in the eye. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors reduce aqueous humor secretion, which may alleviate some of the pressure that causes the effusion. These drugs may be used in conjunction with other treatments, particularly when increased intraocular pressure is a concern.

- Observation: In mild cases of UES or when the condition is stable, close monitoring may be an appropriate management strategy. Regular appointments with an ophthalmologist are required to monitor any changes in the condition, such as the progression of choroidal or retinal detachment. Observation is usually considered when visual acuity is not significantly impaired and the risk of progression is low.

Surgical Management

In more severe cases of UES, surgical intervention is frequently required, especially when there is significant choroidal or retinal detachment, or when conservative medical treatment fails to control the condition.

- Scleral Thinning Procedures: One of the most common surgical treatments for UES is scleral thinning. Because scleral thickening is a common feature of UES, procedures to thin the sclera can improve fluid outflow from the uveal tract. Partial-thickness sclerectomy, which removes small pieces of the sclera, can achieve scleral thinning. This allows the trapped fluid to exit the eye more efficiently, thereby reducing the effusion.

- Scleral Windows: Scleral windows are another surgical option for treating UES. This procedure involves creating small openings or “windows” in the sclera to allow fluid to drain from the uveal tract. Scleral windows are especially effective when other surgical or medical treatments have failed to clear the effusion. The placement and size of the scleral windows are carefully considered based on the effusion’s location and extent.

- Choroidal Drainage: In cases of severe choroidal detachment, direct choroidal drainage may be used. This procedure entails making a small incision in the choroid to drain the accumulated fluid. Choroidal drainage is frequently combined with scleral thinning or scleral windows to prevent fluid buildup. This procedure is usually reserved for more severe cases in which the choroidal detachment poses a serious threat to vision.

- Retinal Reattachment Surgery: If the effusion caused a retinal detachment, surgery to reattach the retina may be required. Pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckling, and vitrectomy are all options for retinal reattachment. The location and extent of the detachment, as well as the underlying cause of the UES, determine the procedure to use. The goal of retinal reattachment surgery is to return the retina to its proper position while preventing further vision loss.

- Vitrectomy: Vitrectomy, or surgical removal of the vitreous gel from the eye, may be performed in conjunction with other procedures, particularly if there is a significant accumulation of fluid or hemorrhage in the vitreous cavity. Vitrectomy improves access to the retina and choroid during surgery and can aid in the treatment of complex cases of UES.

Post-operative Care and Follow-Up

Following surgical intervention, close postoperative monitoring is required to ensure that the effusion resolves and no new complications develop. Patients may require corticosteroids or other anti-inflammatory medications to reduce the risk of postoperative inflammation. Regular follow-up visits with an ophthalmologist are essential for tracking the success of the surgery, assessing the healing process, and detecting any signs of recurrence.

Additional treatments or surgeries may be required if the effusion recurs or if complications such as secondary glaucoma or persistent retinal detachment develop. Long-term management of UES frequently entails a combination of medical and surgical approaches tailored to each patient’s specific needs.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with Uveal Effusion Syndrome is dependent on the severity of the condition and the timing of treatment. With proper management, many patients can achieve condition stabilization and vision preservation. However, if there is a significant delay in diagnosis or treatment, or if the effusion is particularly severe, permanent vision loss may be possible.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach” by Jack J. Kanski and Brad Bowling: This comprehensive textbook offers in-depth information on various ocular conditions, including Uveal Effusion Syndrome. It is a valuable resource for both students and practicing ophthalmologists.

- “Retinal and Choroidal Disorders” edited by J. Fernando Arévalo: This book provides a detailed overview of diseases affecting the retina and choroid, with chapters dedicated to conditions like Uveal Effusion Syndrome. It is an excellent resource for clinicians looking to deepen their understanding of this complex condition.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO provides extensive resources on eye health, including educational materials on rare conditions like Uveal Effusion Syndrome. Their website offers access to the latest research, clinical guidelines, and continuing education opportunities for eye care professionals.

- The Retina Society: This organization is dedicated to advancing knowledge and treatment of retinal diseases. It offers resources for both clinicians and patients, including information on Uveal Effusion Syndrome and related conditions. The society also hosts conferences and publishes research on the latest developments in the field of retinal and choroidal disorders.