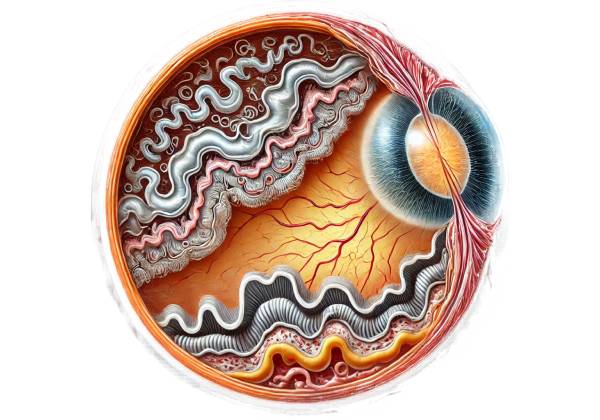

Serpiginous choroiditis, also known as serpiginous chorioretinopathy, is a rare, chronic, and progressive inflammatory disease affecting the choroid and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) of the eye. Serpentine or snake-like lesions spread from the optic disc across the retina, causing significant visual impairment if not properly managed. The disease typically affects both eyes, but it can start unilaterally, and it is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged adults.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye

Understanding serpiginous choroiditis requires a basic understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the eye, particularly the structures involved.

The choroid is a vascular layer of the eye that lies between the retina and the sclera. It contains numerous blood vessels and supplies oxygen and nutrients to the retina’s outer layers, which include the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and photoreceptors. The RPE is a pigmented cell layer located just outside the neurosensory retina that is critical to maintaining visual function. It absorbs excess light, recycles visual pigments, and serves as a barrier between the retina and the choroid, among other functions.

Serpiginous choroiditis is characterized by inflammation of the choroid and RPE, resulting in damage and subsequent visual impairment. The exact cause of this inflammation is unknown, but it is thought to be an autoimmune process in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues.

Clinical Presentation

Serpiginous choroiditis causes a wide range of symptoms, which vary depending on the stage and severity of the disease. The condition is usually chronic and marked by periods of activity and remission. The clinical course is unpredictable, with periods of inactivity followed by reactivation, frequently in previously unaffected areas of the retina.

Early Symptoms

In the early stages, serpiginous choroiditis may present with subtle visual symptoms, such as:

- Blurred Vision: Patients may notice a gradual blurring of vision, which typically begins in one eye. This blurring may be mild at first, but it can worsen as the disease progresses and affects larger areas of the retina.

- Scotomas: Scotomas, or blind spots in the visual field, are a common initial symptom. These blind spots are typically paracentral, meaning they occur near the center of the visual field, and can have a significant impact on activities like reading or driving.

- Photopsia: Patients may experience photopsia, which causes flashes of light or flickering in the affected eye(s). This symptom is more prevalent during periods of active inflammation.

- Metamorphopsia: Metamorphopsia, or vision distortion in which straight lines appear wavy, can occur when the macula, the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision, is involved.

Progressive Disease

Serpiginous choroiditis causes inflammatory lesions to spread in a serpentine pattern from the optic disc to the retina’s periphery. This progression may lead to more pronounced visual disturbances:

- Worsening Scotomas: As the disease progresses, the scotomas may enlarge and coalesce, resulting in significant areas of vision loss. If the macula is damaged, central vision may become compromised, resulting in severe visual impairment.

- Reduced Visual Acuity: Progressive involvement of the macula and surrounding retina can result in a significant reduction in visual acuity, potentially leading to legal blindness if not properly treated.

- Color Vision Changes: Patients may experience changes in color perception, particularly difficulty distinguishing between specific colors, as a result of photoreceptor and RPE damage.

- Night Vision Problems: The condition can impair night vision, making it difficult to see in low light conditions.

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of serpiginous choroiditis is unknown, but it is thought to involve an autoimmune response. For unknown reasons, the immune system targets and attacks the choroid and RPE, causing inflammation and subsequent structural damage. This autoimmune response could be triggered by environmental factors, infections, or other systemic conditions, but specific triggers have yet to be identified.

Histopathological studies have revealed that lesions associated with serpiginous choroiditis primarily affect the choriocapillaris (the choroid’s innermost layer) and the RPE. The inflammation causes atrophy and scarring in these areas, resulting in the clinically identifiable serpentine or geographic lesions.

Serpiginous choroiditis typically begins in the optic disc and spreads centrifugally to the macula and peripheral retina. This progression can take months or years, with intermittent episodes of reactivation. Each reactivation can cause new areas of choroidal and retinal damage, exacerbating the vision problems.

Differential Diagnosis

Serpiginous choroiditis’ clinical presentation can be similar to other conditions, making diagnosis difficult. Differential diagnoses that should be considered are:

- Acute Posterior Multifocal Placoid Pigment Epitheliopathy (APMPPE): APMPPE is an inflammatory condition that affects both the choroid and the RPE, resulting in multiple creamy-white placoid lesions. Unlike serpiginous choroiditis, APMPPE usually affects younger patients, has a faster onset, and often resolves spontaneously without causing significant permanent visual impairment.

- Birdshot Chorioretinopathy: Birdshot chorioretinopathy is another type of autoimmune choroiditis that causes multiple small, round, cream-colored lesions throughout the fundus. It is frequently associated with HLA-A29 positivity and has a slower progression than serpiginous choroiditis.

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Disease: VKH is an autoimmune disorder affecting the eyes, skin, and central nervous system. It can present as diffuse granulomatous choroiditis, resulting in multiple serous retinal detachments that, in the early stages, can resemble serpiginous choroiditis lesions.

- Tuberculous Choroiditis: Tuberculosis can cause choroidal inflammation, resulting in multifocal choroiditis that resembles serpiginous tissue. Tuberculous choroiditis is frequently associated with systemic symptoms and positive Mycobacterium tuberculosis tests.

- Sarcoidosis: Ocular sarcoidosis can result in granulomatous inflammation of the choroid and retina, similar to serpiginous choroiditis. It is usually associated with systemic symptoms like lymphadenopathy and high serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels.

Accurate differentiation between these conditions is critical because management strategies differ significantly. To rule out infectious and systemic causes of choroiditis, a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and laboratory tests is frequently required.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Serpiginous choroiditis is a rare condition, with an estimated incidence of less than one case per 10,000 people. It primarily affects adults aged 30 to 60, with no clear gender predilection. The disease is present all over the world, but its prevalence may differ by region.

Serpiginous choroiditis risk factors are unclear, but some studies suggest a link to autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Genetic predisposition may also be a factor, as some cases have been reported in families, implying a hereditary component.

Effects on Quality of Life

Serpiginous choroiditis can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, especially when the disease progresses to affect the macula and central vision. The disease’s chronic nature, with its cycles of activity and remission, can be discouraging for patients, who may experience periods of visual improvement followed by relapse.

Loss of central vision can severely impair a person’s ability to perform daily tasks such as reading, driving, and recognizing faces, resulting in a loss of independence. The psychological burden of the disease, such as anxiety and depression, must also be considered when managing these patients.

Diagnostic Techniques for Serpiginous Choroiditis

Serpiginous choroiditis is diagnosed using a combination of clinical examination, imaging techniques, and laboratory tests to confirm and distinguish it from other similar conditions.

Clinical Examination

A comprehensive clinical examination by an ophthalmologist is the first step in diagnosing serpiginous choroiditis. The exam typically includes:

- Fundus Examination: The ophthalmologist uses an ophthalmoscope to examine the back of the eye (fundus) for the characteristic lesions of serpiginous choroiditis. These lesions usually manifest as yellowish or grayish areas of chorioretinal atrophy with active borders that spread in a serpentine pattern from the optic disc.

- Visual Acuity Testing: This test assesses the sharpness of the patient’s vision and helps determine the disease’s impact on central vision. A decline in visual acuity could indicate macular involvement.

- **Amsler Grid *Test*: The Amsler grid test detects distortions or scotomas in the central visual field, which are common in serpiginous choroiditis, particularly when the macula is involved. Patients may notice wavy lines or missing areas on the grid, which could indicate active disease.

- Slit-Lamp Biomicroscopy: This procedure allows the ophthalmologist to examine the anterior segment of the eye and the vitreous humor. While serpiginous choroiditis typically affects the posterior segment, slit-lamp biomicroscopy can help rule out anterior segment inflammation and other coexisting conditions.

- Fluorescein Angiography (FA) is an important diagnostic tool in serpiginous choroiditis. This procedure involves injecting a fluorescent dye into an arm vein and photographing its passage through the retinal and choroidal blood vessels. In serpiginous choroiditis, FA typically shows areas of blocked fluorescence corresponding to chorioretinal lesions, as well as leakage at the borders of active lesions, indicating ongoing inflammation.

Imaging Techniques

Advanced imaging techniques are critical for diagnosing and treating serpiginous choroiditis. These imaging modalities aid in determining the extent of the disease, tracking its progression, and guiding treatment decisions.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT produces high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid, allowing for a thorough examination of the retinal layers and RPE. OCT examination of serpiginous choroiditis may reveal thinning or atrophy of the outer retinal layers, disruption of the RPE, and subretinal fluid in active inflammation. OCT is also useful for tracking treatment responses over time.

- Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA): ICGA is similar to FA but uses indocyanine green dye to better visualize the choroidal circulation. ICGA is especially useful in detecting choroidal neovascularization, a complication of serpiginous choroiditis that can result in severe vision loss. It can also help identify subclinical lesions that are not visible on FA.

- Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF): FAF imaging detects the RPE’s natural fluorescence and can identify areas of damage or dysfunction. In serpiginous choroiditis, FAF may show areas of hypoautofluorescence due to RPE atrophy and hyperautofluorescence at the margins of active lesions, indicating ongoing disease activity.

- B-Scan Ultrasonography: When the view of the fundus is obscured, such as by medial opacities, B-scan ultrasonography can be used to evaluate the posterior segment. It can also aid in detecting associated vitreous inflammation or retinal detachment.

Lab Tests

Laboratory tests are frequently used to rule out infectious or systemic causes of choroiditis that may resemble serpiginous choroiditis. These tests include:

- Tuberculosis Testing: Because tuberculous choroiditis can present with similar clinical features, tests like the Mantoux tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assays (e.g., QuantiFERON-TB Gold), and chest X-rays are frequently used to rule out tuberculosis as the underlying cause.

- Blood Tests: To identify any underlying systemic inflammatory or autoimmune disease, blood tests such as a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and autoimmune marker tests (e.g., ANA, RF) may be performed.

- Serology for Infectious Diseases: Serological tests for syphilis, toxoplasmosis, and viral infections (e.g., herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus) may be performed to rule out these infectious etiologies, which can cause similar posterior uveitis.

- Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Levels: Elevated ACE levels can indicate sarcoidosis, which can manifest as choroidal inflammation similar to serpiginous choroiditis. Additional imaging, such as a chest CT scan, may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

In some cases, especially when the diagnosis remains uncertain despite the use of standard diagnostic methods, a retinal or choroidal biopsy may be considered. This invasive procedure involves collecting a tissue sample from the affected area for histopathological analysis. While rarely used, it can provide definitive diagnostic information, especially in atypical or refractory cases.

Treatment Approaches for Serpiginous Choroiditis

Serpiginous choroiditis is difficult to manage because the disease is chronic and relapsing, and there is a risk of significant visual impairment. The primary goals of treatment are to reduce inflammation, stop the progression of lesions, and preserve vision. Treatment typically consists of systemic immunosuppressive therapies, but the exact approach may differ depending on the severity and activity of the disease, as well as the presence of any complications.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

- Corticosteroids: Corticosteroids are the primary treatment for active serpiginous choroiditis. They work by reducing the inflammatory response that causes the disease. Corticosteroids can be administered in a variety of ways:

- Oral Corticosteroids: Prednisone is commonly used as an initial treatment, with doses ranging from 40-60 mg per day and tapering over weeks to months based on clinical response.

- Intravenous Corticosteroids: In cases of severe or rapidly progressing disease, intravenous corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone may be administered in high doses (e.g., 1 gram per day for 3 days) to quickly control inflammation.

- Intravitreal Corticosteroids: For patients with unilateral disease or when systemic corticosteroids are contraindicated, intravitreal corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide) can be used to deliver high doses of the drug directly to the affected eye.

- Steroid-Sparing Agents: Long-term corticosteroid use is associated with significant side effects, including osteoporosis, hypertension, diabetes, and cataract formation. To reduce these risks, steroid-free immunosuppressive agents are frequently introduced as part of the treatment regimen.

- Azathioprine: This immunosuppressant is commonly used to treat autoimmune conditions and can help reduce the frequency and severity of disease flares in serpiginous choroiditis. It is commonly used in conjunction with corticosteroids.

- Mycophenolate Mofetil: Mycophenolate is another immunosuppressive agent that is becoming increasingly popular in the treatment of serpiginous choroiditis. It has a lower risk of side effects than some other immunosuppressants and is effective at keeping patients in remission.

- Methotrexate: Methotrexate is a commonly used immunosuppressant for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, including serpiginous choroiditis. It is commonly used as a steroid-sparing agent and can be given orally or via injection.

- Cyclosporine and Tacrolimus: These calcineurin inhibitors are effective immunosuppressants for refractory disease. They work by inhibiting T-cell activation, which is an important step in the autoimmune process that causes serpiginous choroiditis.

- Biologic Therapies: When standard immunosuppressive therapies are ineffective or poorly tolerated, biologic agents may be considered. These drugs target specific immune system components and can be extremely effective in reducing inflammation.

- Infliximab: Infliximab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), a key cytokine in inflammation. It has shown promise in treating serpiginous choroiditis, especially in patients who do not respond to conventional immunosuppressive therapy.

- Adalimumab: Adalimumab, like infliximab, is a TNF-alpha inhibitor that can help treat refractory serpiginous choroiditis. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection and has been shown to reduce the number of disease flares.

Management of Complications

Serpiginous choroiditis can cause several complications, including choroidal neovascularization (CNV) and macular edema, both of which can result in severe vision loss. Management of these complications frequently requires additional treatments:

- Anti-VEGF Therapy: For patients with CNV, intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents, such as ranibizumab, bevacizumab, or aflibercept, can be used to reduce neovascularization and prevent further retinal damage. Anti-VEGF therapy is typically administered monthly until the CNV is under control.

- Laser Photocoagulation: In some cases, focal laser photocoagulation can be used to treat CNV or active inflammation that does not respond to medical treatment. However, this method is less commonly used due to the risk of collateral damage to the surrounding retina.

- Monitoring and Regular Follow-Up: Because serpiginous choroiditis is chronic, patients require ongoing monitoring to assess disease activity and response to treatment. Regular follow-up visits, which include visual acuity testing, fundus examinations, and imaging studies like OCT and FA, are critical for detecting relapses or complications early on.

Lifestyle Changes and Support

Patients with serpiginous choroiditis may benefit from lifestyle changes that aid in managing the condition and its impact on daily life. These may include:

- Visual Aids: Magnifiers, specialized glasses, and adaptive technology can help patients with significant visual impairment perform daily tasks more effectively.

- Psychological Support: Because serpiginous choroiditis is chronic and unpredictable, patients may find it difficult to cope mentally. Psychological counseling and support groups can offer important emotional support and coping strategies.

- Sun Protection: Because UV exposure can exacerbate inflammation, patients should wear sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats outside to protect their eyes from the sun.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Uveitis: Fundamentals and Clinical Practice” by Robert B. Nussenblatt and Scott M. Whitcup: This comprehensive textbook covers all aspects of uveitis, including serpiginous choroiditis, providing in-depth information on diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies.

- “Vitreoretinal Disease: The Essentials” by David R. Chow and Suber S. Huang: This book offers a detailed overview of various retinal diseases, including serpiginous choroiditis, with a focus on clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, and treatment options.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO provides extensive resources on eye diseases, including serpiginous choroiditis. Their website offers educational materials for patients and updates on the latest research and treatment guidelines.

- The Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation (OIUF): OIUF is dedicated to providing information and support for patients with uveitis and related conditions. They offer resources on disease management, patient education, and access to support groups.

- Macular Society: The Macular Society provides resources and support for individuals with macular conditions, including those caused by serpiginous choroiditis. They offer information on coping with vision loss, treatment options, and support services for patients and their families.