Introduction to Dominant Optic Atrophy

Dominant Optic Atrophy (DOA) is a hereditary eye condition characterized by progressive degeneration of the optic nerves, which causes visual impairment. DOA typically manifests in the first decade of life and primarily affects the transmission of visual information from the eyes to the brain. This condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, which means that only one copy of the altered gene in each cell is required to cause the disorder. DOA is the most common hereditary optic neuropathy, and it can have a significant impact on the quality of life for those affected. Understanding the underlying mechanisms, progression, and associated factors is critical for successful management and support.

Dominant Optic Atrophy: Insights

Pathology and Etiology

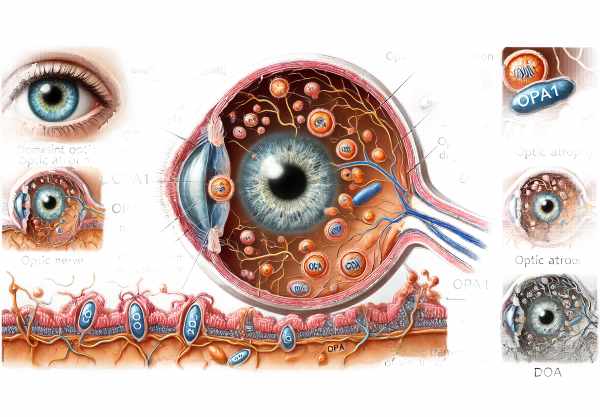

Dominant Optic Atrophy is caused by mutations in the OPA1 gene, which encodes a protein involved in mitochondria function and integrity. Mitochondria are essential for cellular energy production, and their dysfunction can cause cell death. DOA degeneration primarily affects the retinal ganglion cells and their axons, which form the optic nerve. This causes a gradual loss of vision due to the impaired transmission of visual signals from the retina to the brain.

Genetic Factors

The OPA1 gene mutation is inherited autosomally dominantly, which means that the condition can be passed down through only one defective gene from an affected parent. Affected individuals have a 50% chance of passing on the mutation to their offspring. While the OPA1 gene is the most frequently implicated, other genetic mutations can cause similar optic neuropathies, complicating the genetic landscape of DOA.

Symptoms and Presentation

The symptoms of Dominant Optic Atrophy vary between individuals, but generally include:

- Progressive Vision Loss: The hallmark of DOA is a gradual decline in visual acuity that typically begins in early childhood and lasts into adulthood. The degree of vision loss varies, with some people retaining relatively good vision and others experiencing significant impairment.

- Color Vision Deficiency: Many people with DOA have difficulty distinguishing colors, especially shades of blue and yellow. This color vision deficiency is caused by the loss of retinal ganglion cells, which process color information.

- Central Vision Loss: DOA primarily affects central vision, making it difficult to perform tasks requiring detailed vision, such as reading and recognizing faces. Peripheral vision is typically less affected, allowing people to maintain some functional vision.

- Optic Disc Pallor: An ophthalmologic examination frequently reveals optic disc pallor, which is a whitening of the optic nerve head and indicates nerve fiber loss. This is a key DOA diagnostic sign.

Associated Conditions

Individuals with Dominant Optic Atrophy may suffer from other health problems as a result of the underlying mitochondrial dysfunction. These may include:

- Hearing Loss: Sensorineural hearing loss is fairly common in people with DOA, as the same mitochondrial dysfunction that affects the optic nerves can also affect auditory pathways.

- Neuropathy: Peripheral neuropathy, or damage to the peripheral nerves, can cause muscle weakness and sensory disturbances.

- Muscle Weakness: Generalized muscle weakness and fatigue may occur as a result of impaired cell energy production.

- Other Ocular Conditions: There is a higher risk of developing glaucoma and cataracts, which can complicate the visual prognosis.

Effects on Quality of Life

Dominant Optic Atrophy can have a significant impact on quality of life, particularly for those with severe vision loss. Daily tasks like reading, driving, and recognizing faces become difficult, affecting independence and social interactions. Children with DOA may struggle in academic settings, necessitating special accommodations and support.

Progress and Prognosis

The progression of Dominant Optic Atrophy varies greatly between individuals. Some may have relatively stable vision for many years, whereas others may experience a rapid decline in visual acuity. The rate of progression can be influenced by various factors, including the specific genetic mutation and the presence of associated conditions. Despite the variability, DOA usually does not result in complete blindness, and many people retain some functional vision throughout their life.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating Dominant Optic Atrophy from other optic neuropathies and hereditary conditions is critical for effective treatment. Conditions that must be considered in the differential diagnosis are:

- Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy (LHON): Another mitochondrial disorder that causes optic neuropathy, LHON typically manifests as sudden, severe vision loss in young adults, distinguishing it from DOA’s more gradual onset.

- Glaucoma: Glaucoma is characterized by optic nerve damage, which is frequently caused by increased intraocular pressure. Although glaucoma can present with similar optic disc changes, it has distinct clinical features and risk factors.

- Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Optic neuritis, an inflammatory condition associated with MS, can result in acute vision loss and changes to the optic disc. However, the pattern of vision loss and other neurological symptoms may help distinguish it from DOA.

- Nutritional Optic Neuropathy: Deficiencies in nutrients such as vitamin B12 and folate can cause optic neuropathy. A detailed dietary history and laboratory tests can help to distinguish this condition from DOA.

Prevention Tips

- Genetic Counseling: For families with a history of Dominant Optic Atrophy, genetic counseling is critical. It explains the risk of passing the condition to offspring and discusses reproductive options.

- Regular Eye Examinations: Early detection through routine eye exams can aid in monitoring the progression of DOA and effectively managing symptoms. Ophthalmologists can offer advice on visual aids and other supportive measures.

- Healthy Lifestyle: Maintaining a healthy lifestyle, which includes a well-balanced diet high in antioxidants, can benefit overall eye health. Vitamins A, C, and E, as well as omega-3 fatty acids, can help keep your retina healthy.

- Avoid Smoking and Excessive Alcohol: Smoking and drinking too much alcohol can exacerbate oxidative stress, potentially worsening mitochondrial function. Avoiding these habits can help protect your vision.

- Protect Eyes from UV Light: Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses can protect the eyes from additional stress and damage caused by sunlight exposure.

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Proper management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension is critical, as they can affect overall health and well-being, including vision.

- Hearing Check-Ups: Given the link to hearing loss, regular audiometric evaluations can help detect and address hearing problems early on, improving overall quality of life.

- Stay Informed: Staying up to date on the latest research and advances in the understanding and treatment of Dominant Optic Atrophy can provide valuable insights and access to new therapies.

- Support Networks: Joining support groups and networks for people with hereditary optic neuropathy can provide emotional support, shared experiences, and practical advice on how to manage the condition.

Diagnostic methods

Dominant optic atrophy is diagnosed using a combination of clinical evaluation, genetic testing, and advanced imaging techniques. A correct diagnosis is critical for distinguishing DOA from other optic neuropathies and hereditary disorders.

Standard Diagnostic Techniques

- Comprehensive Eye Examination: The initial step in diagnosing DOA is to conduct a thorough eye examination. This includes visual acuity tests, color vision tests, and fundoscopy to examine the optic disc for pallor and nerve fiber layer thinning.

- Visual Field Testing: Visual field tests, such as automated perimetry, evaluate the patient’s peripheral vision and can detect specific patterns of vision loss linked to DOA.

- Color Vision Tests: Color vision deficiencies, particularly in the blue-yellow spectrum, are prevalent in DOA. Color vision loss can be quantified using tests such as the Ishihara plates and the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 hue test.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT generates high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina, allowing for a thorough examination of the retinal nerve fiber layer. In DOA, OCT typically shows RNFL thinning, particularly in the temporal quadrant.

Innovative Diagnostic Techniques

- Genetic Testing: Genetic testing is required to confirm a diagnosis of DOA. Mutations that cause the condition can be identified by sequencing the OPA1 gene. Genetic counseling should be provided alongside testing to discuss the implications of the results.

- Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF): FAF imaging detects metabolic changes in the retina by recording the natural fluorescence emitted by lipofuscin in the retinal pigment epithelium. FAF can identify areas of retinal degeneration and optic nerve damage.

- Electrophysiological Testing: VEP and ERG tests assess the functional integrity of the visual pathways. VEP can detect abnormalities in the transmission of visual signals from the retina to the brain, indicating optic nerve dysfunction in DOA.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): While MRI is primarily used to rule out other conditions, it can provide detailed images of the optic nerves and surrounding structures, assisting in the diagnosis of optic atrophy and ruling out compressive lesions or other neurological disorders.

- Advanced Imaging Techniques: Newer imaging modalities, such as adaptive optics and high-resolution OCT angiography, are being investigated for their ability to provide more detailed assessments of retinal and optic nerve health in DOA patients.

Diagnostic Criteria

By combining these diagnostic methods, clinicians can gain a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s visual function and the structural integrity of the optic nerves. DOA diagnostic criteria include a progressive decline in visual acuity, color vision deficits, optic disc pallor seen on fundoscopy, and genetic testing to confirm OPA1 gene mutations.

Effective Treatment for Dominant Optic Atrophy

The treatment for dominant optic atrophy focuses on symptom management, slowing disease progression, and improving the patient’s quality of life. While there is no cure for DOA, there are several strategies that can help manage its effects.

Standard Treatment Options

- Vision Aids: Prescription glasses or contact lenses can help correct refractive errors and improve visual acuity to some degree. Low vision aids, such as magnifying lenses and telescopic glasses, can help with daily tasks that require precise vision.

- Color Vision Filters: Specially tinted lenses can improve color discrimination in people who have significant color vision deficiencies. These lenses can enhance visual comfort and functionality in certain lighting conditions.

- Occupational Therapy: Occupational therapy helps patients adjust to vision loss by teaching them strategies for performing daily tasks. This may include instruction in the use of assistive devices and techniques for maximizing remaining vision.

Innovative and Emerging Therapies

- Gene Therapy: Gene therapy seeks to correct the underlying genetic defect in DOA. Experimental methods include delivering a normal copy of the OPA1 gene to retinal cells via viral vectors. Early-stage research is promising, but clinical applications are still being developed.

- Mitochondrial Targeted Therapies: Given the importance of mitochondrial dysfunction in DOA, therapies aimed at mitochondrial health are being investigated. This includes antioxidants, mitochondrial protectors, and compounds that improve mitochondrial function.

- Stem Cell Therapy: Stem cell therapy has the potential to regenerate damaged optic nerve cells. Researchers are working to develop methods for transplanting stem cells into the retina to restore function in DOA patients.

- Neuroprotective Agents: Researchers are looking into drugs that protect nerve cells from degeneration. These compounds either inhibit cell death pathways or promote cell survival and function.

- Visual Prosthetics: Advanced visual prosthetics, such as bionic eyes and retinal implants, are being developed to provide artificial vision to people who have severe vision loss. These devices can bypass damaged optic nerves and directly stimulate the visual cortex or healthy retinal cells.

Supportive Measures

- Regular Monitoring: Regular eye exams and visual field tests are required to monitor disease progression and adjust management strategies as necessary.

- Psychological Support: Living with progressive vision loss can be difficult. Psychological counseling and support groups can offer emotional support as well as practical advice for dealing with the effects of DOA on a daily basis.

- Education and Advocacy: Educating patients and their families about DOA, as well as advocating for accommodations in educational and occupational settings, can help people with DOA reach their full potential, regardless of their visual limitations.

Trusted Resources

Books

- “Inherited Retinal Disease: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and Management” by Stephen H. Tsang

- “Genetics for Ophthalmologists: The Molecular Genetic Basis of Ophthalmic Disorders” by Graeme C.M. Black and Melanie Hingorani

- “Optic Nerve Disorders: Diagnosis and Management” by Jane C. S. Perrin