Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is the most common type of glaucoma, a group of eye conditions marked by optic nerve damage and elevated intraocular pressure (IOP). This chronic and progressive condition causes gradual vision loss and, if untreated, can lead to blindness. POAG is a major public health concern because it is asymptomatic in its early stages, making regular screening and early detection critical for maintaining vision.

Pathophysiology

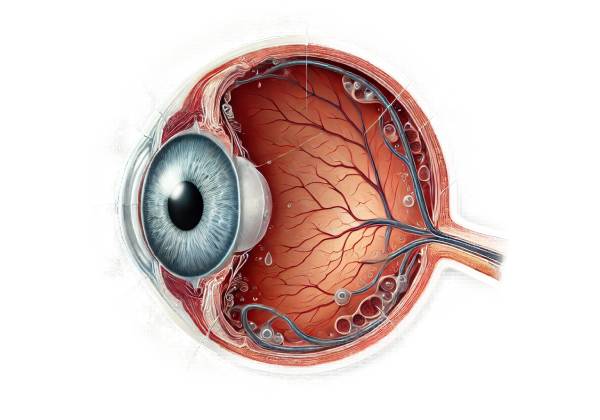

POAG’s primary pathology affects the optic nerve, which transmits visual information from the retina to the brain. POAG is characterized by the gradual and progressive loss of retinal ganglion cells and their axons, which causes characteristic changes in the optic nerve head (optic disc) and visual field defects. Elevated intraocular pressure is a major risk factor for POAG, but the exact mechanism by which IOP causes optic nerve damage is unknown.

The eye continuously produces aqueous humor, a clear fluid that nourishes and keeps the eye in shape. The ciliary body produces this fluid, which flows through the pupil into the anterior chamber before draining through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal and eventually into the bloodstream. In POAG, the trabecular meshwork becomes less effective at draining aqueous humor, resulting in an increase in IOP. However, some people with POAG have normal IOP, indicating that other factors, such as vascular dysregulation and genetic predisposition, are also involved.

Epidemiology

POAG is the leading cause of irreversible blindness globally, affecting millions of people. The prevalence of POAG varies according to age, race, and family history. It is more common in people over the age of 40 and becomes more prevalent as they age. African Americans and people of Afro-Caribbean descent are at a higher risk and develop the condition at a younger age than Caucasians. Furthermore, a family history of POAG significantly raises the risk, emphasizing the importance of genetic factors.

Risk Factors

A variety of risk factors contribute to the development and progression of POAG:

- Age: The risk of POAG increases with age, especially after 40. The prevalence increases significantly in people over the age of 60.

- Race: African Americans and people of Afro-Caribbean descent are at a higher risk and frequently experience more severe disease progression. Hispanic populations have a higher prevalence than Caucasians.

- Family History: A positive family history of POAG is a significant risk factor. First-degree relatives of affected people face a significantly higher risk.

- Elevated Intraocular Pressure: High IOP is the most important modifiable risk factor. Although not all people with elevated IOP develop POAG, and not all POAG patients have elevated IOP, it is still an important aspect of the disease.

- Corneal Thickness: A thin central corneal thickness is associated with a higher risk of POAG. Thinner corneas may cause underestimation of IOP readings and are independently associated with increased risk.

- Myopia: Severe nearsightedness is associated with a higher risk of developing POAG.

- Systemic Conditions: Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease all increase the risk of POAG. The precise mechanisms that link these conditions to glaucoma are not fully understood.

- Genetic Factors: MYOC, OPTN, and CYP1B1 are among the genes linked to POAG. These genetic factors help explain the disease’s heritability and variability.

Clinical Presentation

POAG is often asymptomatic in its early stages, earning it the nickname “the silent thief of sight.” As the disease progresses, patients may notice visual field defects, which typically begin peripherally and progress to the central vision. The loss of peripheral vision may go unnoticed until significant optic nerve damage has occurred. Common indications and symptoms include:

- Visual Field Loss: Initially, patients may notice subtle defects in their peripheral vision, which can progress to tunnel vision as the disease progresses. Central vision is usually preserved until the later stages.

- Optic Disc Changes: The optic disc shows characteristic changes such as increased cupping (enlargement of the optic cup), thinning of the neuroretinal rim, and notching. An eye care professional can detect these changes by performing a dilated fundoscopic examination.

- Elevated Intraocular Pressure: Although not all patients with POAG have elevated IOP, a significant number do. Regular IOP monitoring is critical for detecting and managing the condition.

- Asymptomatic Early Stages: In the early stages, POAG is usually asymptomatic, emphasising the importance of regular eye exams, particularly for those at higher risk.

Differential Diagnosis

POAG must be distinguished from other types of glaucoma and conditions that may mimic its symptoms. This includes:

- Normal-Tension Glaucoma (NTG): A subtype of POAG that causes optic nerve damage despite normal IOP. The pathophysiology is unclear, but it may involve vascular factors.

- Secondary Open-Angle Glaucoma: Secondary open-angle glaucoma can be caused by conditions such as pseudoexfoliation syndrome, pigment dispersion syndrome, or steroid-induced glaucoma, and it must be distinguished from POAG.

- Angle-Closure Glaucoma: Unlike POAG, angle-closure glaucoma causes a narrow or closed anterior chamber angle, resulting in sudden increases in IOP and acute symptoms such as pain and vision loss.

- Ocular Hypertension: High IOP without optic nerve damage or visual field loss. These patients are at an increased risk of developing POAG and should be monitored.

Complications

Untreated or inadequately managed POAG can cause serious complications, including:

- Severe Vision Loss and Blindness: Progressive optic nerve damage causes irreversible vision loss, which can progress to total blindness if left untreated.

- Decreased Quality of Life: POAG-related vision loss can have an impact on daily activities, independence, and overall quality of life.

- Increased Risk of Falls and Accidents: Peripheral vision loss raises the risk of falls and accidents, especially among older adults.

- Economic Burden: POAG has a significant economic impact due to the high cost of long-term treatment, frequent monitoring, and potential loss of productivity.

Prognosis

Individuals with POAG’s prognosis is determined by a number of factors, including the stage at which they are diagnosed, their response to treatment, and adherence to management plans. Early detection and consistent treatment can significantly slow disease progression while preserving vision. However, POAG is a chronic condition that necessitates ongoing monitoring and management. Advances in diagnostic techniques and treatments continue to improve the outcomes for patients with POAG.

Understanding POAG is critical for timely detection and management. Regular eye exams, particularly for high-risk individuals, are critical to preventing vision loss and maintaining eye health. Many people with POAG can maintain good vision and a high quality of life if they receive appropriate treatment and follow management plans.

Diagnostic methods

A comprehensive eye examination is required to diagnose primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), as well as a battery of diagnostic tests to assess the structure and function of the optic nerve and measure intraocular pressure (IOP). Early detection is critical for avoiding vision loss and managing the condition effectively. The following are key diagnostic methods for identifying POAG:

Tonometry

Tonometry is the primary way to measure intraocular pressure. Tonometers come in a variety of types, including:

- Goldmann Applanation Tonometry: Known as the gold standard for measuring IOP, this method involves flattening a small area of the cornea and measuring the force required to do so. It gives accurate and reliable IOP readings.

- Non-Contact Tonometry (NCT): Also known as the “air puff” test, NCT flattens the cornea with a burst of air before measuring IOP. While less precise than Goldmann tonometry, it is faster and does not involve contact with the cornea.

- Tono-Pen: A handheld device that measures IOP through brief contact with the cornea. It is useful in a variety of clinical settings, including those where Goldmann tonometry is not feasible.

Ophthalmoscopy

Ophthalmoscopy allows for direct visualization of the optic nerve head (optic disc) to detect glaucomatous damage. This examination can be carried out using:

- Direct Ophthalmoscopy is a handheld device that magnifies the optic disc. While simple to use, it has a limited field of view.

- Indirect Ophthalmoscopy: This technique offers a broader field of view and is frequently used in conjunction with a slit-lamp biomicroscope for a more thorough examination.

- Fundus Photography: High-resolution images of the optic disc are taken to record and compare over time. This method aids in monitoring changes in the optic nerve head.

Visual Field Testing

Visual field testing, also known as perimetry, evaluates the patient’s field of vision and identifies functional deficits caused by glaucoma. Common methods include:

- Automated Perimetry: Devices such as the Humphrey Field Analyzer map the visual field by presenting light stimuli at different locations and recording the patient’s responses. This test detects common patterns of vision loss associated with POAG.

- Manual Perimetry: Also known as Goldmann perimetry, this test requires a technician to manually present light stimuli and record the patient’s responses. It is helpful for patients who struggle with automated testing.

Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT)

OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina and optic nerve head. It measures the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and the ganglion cell complex (GCC), which are both affected by POAG. OCT is extremely useful for detecting early structural changes in the optic nerve and retina before functional vision loss develops.

Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy is the examination of the eye’s anterior chamber angle using a special contact lens known as a gonioscope. This test is critical for distinguishing POAG from other types of glaucoma, including angle-closure glaucoma. Gonioscopy aids in the diagnosis of open-angle glaucoma by determining the angle’s openness.

Pachymetry

Pachymetry measures corneal thickness, which is necessary for accurately interpreting IOP readings. A thinner cornea can result in an underestimation of IOP, whereas a thicker cornea can lead to an overestimation. Knowing the corneal thickness enables adjustments in IOP measurements, resulting in a more accurate assessment of the risk of POAG.

Heidelberg Retinal Tomography(HRT)

HRT is a laser imaging technique that yields a three-dimensional topographic map of the optic nerve head. This test helps to quantify optic disc parameters like cup-to-disc ratio and rim area, which are important for diagnosing and monitoring glaucoma.

Confocal Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy

This imaging technique employs a scanning laser to produce detailed images of the optic nerve head and its surrounding structures. It provides quantitative data on optic disc morphology and can detect subtle changes over time, allowing for early diagnosis and monitoring of POAG.

Electroretinography (ERG)

ERG measures the retina’s electrical responses to light stimuli. Specific patterns of retinal dysfunction can be detected in POAG, indicating additional optic nerve damage and retinal ganglion cell loss.

Genetic Testing

Although not commonly used in clinical practice, genetic testing can detect mutations associated with an increased risk of developing POAG. Understanding a patient’s genetic predisposition can help with risk assessment and individualized management strategies.

Frequency-Doubling Technology (FDT) Perimeter

FDT perimetry is a type of visual field test that employs low spatial frequency gratings to detect early glaucoma damage. It is extremely sensitive to the loss of magnocellular pathway function, which is common in the early stages of POAG.

Primary Open Angle Glaucoma Management

Managing primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) requires a multifaceted approach that focuses on lowering intraocular pressure (IOP) in order to prevent or slow optic nerve damage and preserve vision. The severity of the disease, the patient’s health status, and the patient’s response to therapy all influence treatment plans. Medication, laser therapy, and surgical interventions are the most common strategies for managing POAG.

Medications

Medications are frequently the first line of treatment for POAG, and they work by either decreasing aqueous humor production or increasing its outflow. The primary categories of medications include:

- Prostaglandin Analogues: These drugs, including latanoprost, bimatoprost, and travoprost, increase aqueous humor outflow via the uveoscleral pathway. They are highly effective at lowering IOP and are typically administered once daily.

- Beta-blockers: Drugs such as timolol and betaxolol reduce aqueous humor production. They are typically used once or twice daily and are frequently combined with prostaglandin analogues to improve efficacy.

- Alpha Agonists: Drugs like brimonidine reduce aqueous humor production while increasing uveoscleral outflow. They are usually administered twice a day.

- Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: These medications, which include dorzolamide and brinzolamide, decrease aqueous humor production. They can be used topically or systemically, with topical administration being more common due to fewer systemic side effects.

- Rho Kinase Inhibitors: Netarsudil, a relatively new glaucoma treatment, works by increasing trabecular outflow. They are commonly used in conjunction with other IOP-lowering medications.

Laser Therapy

Laser therapy is an effective treatment option for patients who do not respond well to medications or prefer a non-pharmacological approach. The main laser treatments for POAG are:

- Selective Laser Trabeculoplasty (SLT): SLT focuses on the trabecular meshwork to improve aqueous humor outflow. It employs a low-energy laser and is repeatable if necessary. SLT is frequently considered when medication is insufficient or as an initial therapy.

- Argon Laser Trabeculoplasty (ALT): Like SLT, ALT uses an argon laser to treat the trabecular meshwork. However, ALT is associated with greater thermal damage than SLT and is less widely used today.

Surgical Interventions

Surgery is considered for patients with advanced POAG or those who cannot achieve adequate IOP control with medications and laser therapy. The most common surgical procedures are:

- Trabeculectomy: This surgery removes a portion of the trabecular meshwork to create a new drainage pathway for the aqueous humor. Trabeculectomy is highly effective in lowering IOP, but it has risks such as infection, scarring, and vision changes.

- Glaucoma Drainage Devices (GDDs): Also referred to as aqueous shunts or tubes, these devices allow aqueous humor to drain through an implanted tube. Examples include the Ahmed, Baerveldt, and Molteno implants. GDDs are frequently used in patients who have failed trabeculectomy or have a specific type of glaucoma.

- Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS): MIGS procedures, including the iStent, XEN Gel Stent, and Hydrus Microstent, provide less invasive options with shorter recovery times and fewer complications. They are usually considered for patients with mild to moderate POAG.

Lifestyle and Supportive Measures

In addition to medical, laser, and surgical treatments, lifestyle changes and supportive measures play an important role in managing POAG:

- Regular Eye Exams: Frequent monitoring of IOP, optic nerve health, and visual fields is critical for detecting disease progression and adjusting treatment plans.

- Medication Adherence: Ensuring that patients understand the importance of following prescribed medication regimens is critical for effective IOP control.

- Healthy Lifestyle: Leading a healthy lifestyle, which includes regular exercise, a balanced diet, and quitting smoking, can improve overall eye health and lower the risk of glaucoma progression.

- Patient Education: Educating patients about POAG, its potential consequences, and the importance of ongoing treatment enables them to manage their condition effectively.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Glaucoma: A Patient’s Guide to the Disease” by Graham E. Trope: This book provides comprehensive information on glaucoma, including its diagnosis, treatment options, and patient management strategies.

- “The Glaucoma Handbook” by Ivan Goldberg: A thorough resource covering the various aspects of glaucoma, from understanding the condition to the latest advancements in treatment.

Organizations

- Glaucoma Research Foundation (GRF): The GRF offers extensive information on glaucoma research, treatment options, and patient support. GRF Website

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO provides resources and guidelines for eye health, including detailed information on glaucoma and its management. AAO Website

- National Eye Institute (NEI): The NEI conducts and supports research on eye diseases and provides educational resources on glaucoma and other eye conditions. NEI Website