Tendons are robust, fibrous connective tissues that attach muscles to bones, enabling the transmission of force and facilitating movement. They play an essential role in the musculoskeletal system by providing stability, storing elastic energy, and aiding in proprioception. Whether you’re an athlete, a healthcare professional, or someone interested in maintaining your physical performance, understanding tendon anatomy, common disorders, and treatment strategies is crucial for injury prevention and effective rehabilitation. This guide delves deeply into the structure, functions, common conditions, diagnostic methods, treatment options, and lifestyle tips necessary to optimize tendon health.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Structure

- Macroscopic Anatomy

- Microscopic Structure

- Tendon Attachments

- Key Functional Roles

- Common Tendon Disorders

- Diagnostic Techniques

- Treatment Approaches

- Effective Supplements

- Lifestyle & Maintenance Tips

- Trusted Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Disclaimer & Sharing

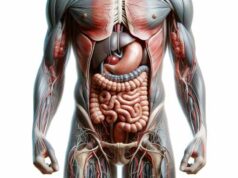

Anatomical Structure of Tendons

Tendons are critical components of the musculoskeletal system, acting as the interface between muscle and bone. They are composed primarily of collagen fibers, which provide high tensile strength, and a small percentage of elastin, which imparts flexibility. This intricate structure allows tendons to endure high mechanical loads and transmit forces generated by muscle contractions efficiently. Tendons are typically white, glistening, and vary in shape—ranging from cylindrical to flat structures—depending on their location and function. Their unique composition and organization are essential for efficient movement, injury prevention, and overall joint stability.

Macroscopic Anatomy of Tendons

At the macroscopic level, tendons exhibit distinctive features that reflect their role in force transmission and movement.

Gross Appearance

Tendons are generally white and shiny due to their high collagen content. Their appearance is influenced by the degree of hydration and the alignment of collagen fibers. In cross-section, tendons may appear as flattened bands or round, cylindrical structures depending on their anatomical location.

Tendon Sheaths

In areas where tendons pass over joints or experience significant friction, they are enclosed in tendon sheaths. These tubular structures, lined with a synovial membrane, secrete synovial fluid that lubricates the tendon and minimizes friction during movement.

Paratenon and Epitenon

Not all tendons are surrounded by a true synovial sheath. Many are instead encased in a loose connective tissue layer called the paratenon, which provides a gliding surface and houses blood vessels and nerves. Closely related is the epitenon, a thin layer of connective tissue that covers the entire tendon, merges with the paratenon, and plays a vital role in vascular supply and innervation.

Endotenon

Within the tendon, the endotenon is a delicate connective tissue that partitions the tendon into bundles known as fascicles. It contains small blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerve fibers, ensuring that each fascicle receives the nutrients required for maintenance and repair.

Microscopic Structure of Tendons

At the microscopic level, the strength and functionality of tendons are attributed to their highly organized collagen matrix and specialized cellular components.

Collagen Fibers

Collagen fibers form the primary structural framework of tendons, constituting approximately 70–80% of their dry weight. These fibers are mainly composed of type I collagen, known for its high tensile strength. Collagen molecules aggregate to form fibrils, which then bundle into fibers. The parallel alignment of these fibers is critical for efficient force transmission.

Tenocytes

Tenocytes, the specialized fibroblasts within tendons, are responsible for synthesizing and maintaining the extracellular matrix. They are spindle-shaped cells that produce collagen and other essential proteins, ensuring that the tendon’s structural integrity is preserved. Their cytoplasmic processes allow them to communicate and coordinate the repair process following injury.

Ground Substance

The ground substance is the non-fibrous component of the extracellular matrix, composed of proteoglycans, glycosaminoglycans, and water. It facilitates nutrient diffusion to tenocytes and contributes to the viscoelastic properties of tendons, allowing them to absorb and dissipate mechanical energy during movement.

Tendon Attachments: Myotendinous & Osteotendinous Junctions

Tendons anchor muscles to bones, and their attachments are highly specialized to transmit force and withstand stress.

Myotendinous Junction

The myotendinous junction is where the tendon connects to the muscle fibers. This region features an interdigitation of collagen fibers with muscle cells, forming a secure interface that efficiently transfers the force generated by muscle contraction. This junction is critical for preventing strain injuries and ensuring smooth movement.

Osteotendinous Junction

At the osteotendinous junction, tendons attach to bones. Here, the tendon fibers gradually transition into fibrocartilage and then mineralized fibrocartilage before integrating with the bone. This gradation in tissue composition minimizes stress concentration at the attachment site, thereby reducing the risk of tendon avulsion or rupture.

Key Functional Roles of Tendons

Tendons play a multifaceted role in the musculoskeletal system, crucial for movement, stability, and proprioception.

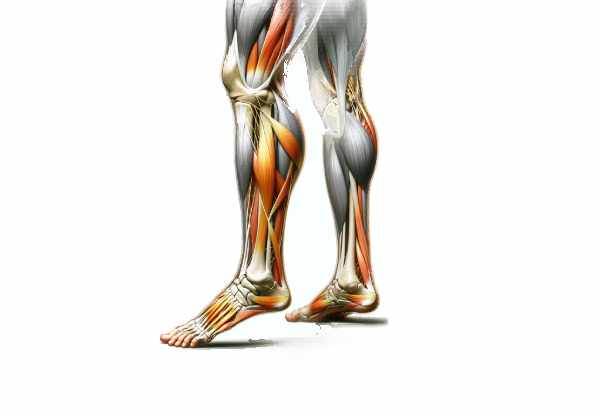

Force Transmission

The primary function of tendons is to transmit the force generated by muscle contractions to bones, enabling movement. When a muscle contracts, its tendon acts as a cable that pulls on the bone, resulting in joint movement. This process is fundamental to all voluntary movements, from simple tasks like walking to complex athletic activities.

Elastic Energy Storage

Tendons act as biological springs that store elastic energy during muscle contraction. For example, during running or jumping, tendons stretch and store energy, which is then released during the subsequent movement phase, enhancing efficiency and reducing the metabolic cost of movement.

Joint Stability

By anchoring muscles to bones, tendons contribute significantly to joint stability. They help maintain proper alignment of the skeletal system and prevent excessive or abnormal movements that could lead to dislocations or injuries. For instance, the rotator cuff tendons are essential for stabilizing the shoulder joint during dynamic movements.

Proprioception

Tendons contain specialized mechanoreceptors that provide proprioceptive feedback to the central nervous system. This information about muscle tension and joint position is critical for coordinating precise movements and maintaining balance and posture.

Healing and Repair

Although tendons have a limited capacity for healing due to their low vascularity, they do undergo repair processes following injury. Tenocytes are key players in synthesizing new collagen and extracellular matrix components to restore tendon integrity. However, the repaired tendon may form scar tissue that is less elastic and more prone to re-injury.

Adaptation to Mechanical Load

Tendons adapt to changes in mechanical load through mechanotransduction, the process by which mechanical stimuli are converted into cellular signals. Regular exercise can stimulate tendons to strengthen and become more resilient, whereas prolonged inactivity can lead to tendon degeneration and weakness.

Common Tendon Disorders

Despite their robust structure, tendons are vulnerable to various disorders, especially due to overuse, acute injuries, and degenerative changes. Here are some of the most prevalent tendon-related conditions:

Tendinitis

Tendinitis, or tendonitis, is the inflammation of a tendon typically caused by repetitive overuse or an acute injury. Common forms include:

- Achilles Tendinitis: Characterized by pain and stiffness in the heel and lower leg, common among runners.

- Patellar Tendinitis: Often known as jumper’s knee, causing pain around the kneecap, common in athletes who jump frequently.

- Rotator Cuff Tendinitis: Affects the shoulder tendons, leading to pain and limited mobility, often seen in those performing repetitive overhead activities.

- Tennis Elbow (Lateral Epicondylitis): Involves pain in the tendons of the elbow due to repetitive wrist and arm movements.

Tendinosis

Tendinosis is a chronic degenerative condition marked by the deterioration of collagen fibers in the tendon. Unlike tendinitis, tendinosis is characterized by minimal inflammation and results from repetitive strain and inadequate healing.

Tendon Rupture

A tendon rupture occurs when a tendon tears completely or partially, often due to a sudden, forceful muscle contraction or direct trauma. Common examples include:

- Achilles Tendon Rupture: Leading to a sharp pain in the heel and difficulty walking.

- Rotator Cuff Tear: Which can result from acute injury or chronic wear, impairing shoulder function.

- Biceps Tendon Rupture: Causing pain and visible deformity in the affected arm.

Tenosynovitis

Tenosynovitis is the inflammation of the synovial sheath surrounding a tendon, commonly affecting the wrists, hands, and fingers.

- De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis: Involves the tendons on the thumb side of the wrist, causing pain and swelling.

- Trigger Finger: Characterized by pain, stiffness, and a popping sensation when the finger is moved.

Calcific Tendonitis

Calcific tendonitis is marked by the deposition of calcium crystals within a tendon, leading to pain and inflammation. It is most commonly seen in the rotator cuff tendons.

Bursitis

Although bursitis affects the bursa rather than the tendon directly, it often coexists with tendon disorders. Inflammation of the bursa can exacerbate tendon pain and restrict movement.

Degenerative Tendinopathy

Degenerative tendinopathy is a chronic condition characterized by the gradual breakdown of tendon tissue due to aging, overuse, or inadequate healing from previous injuries. It results in chronic pain and reduced tendon function.

Repetitive Stress Injury (RSI)

RSI is an umbrella term for conditions caused by repetitive motions that stress the tendons. Common symptoms include pain, stiffness, and decreased function, often affecting the wrists, elbows, and shoulders.

Diagnostic Techniques for Tendon Disorders

A thorough and accurate diagnosis is essential for effective treatment of tendon disorders. A combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and specialized tests is typically employed.

Medical History and Physical Examination

- Medical History:

A detailed history is gathered to understand the onset, duration, and nature of symptoms, as well as the patient’s activity level and any previous injuries. - Physical Examination:

The clinician assesses for swelling, tenderness, range of motion limitations, and specific movements that elicit pain. Special provocative tests (e.g., Finkelstein test for De Quervain’s) can help pinpoint the affected tendon.

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasound:

A non-invasive technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce images of soft tissues. It can detect tendon tears, inflammation, calcifications, and guide injections. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI offers detailed images of soft tissues, making it ideal for diagnosing partial or complete tendon tears, tendinosis, and associated muscle or joint injuries. - X-rays:

Although less detailed for soft tissues, X-rays are useful for detecting calcific deposits and evaluating bone structures related to tendon attachments. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT scans provide cross-sectional images that are useful for complex tendon injuries or when evaluating associated bony abnormalities.

Functional and Electrophysiological Tests

- Range of Motion and Strength Tests:

These tests assess the functional impact of tendon disorders on joint movement and muscle strength. - Electromyography (EMG) and Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS):

While primarily used for evaluating nerve function, these tests can detect muscle weakness or nerve involvement in chronic tendon injuries.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood Tests:

Laboratory tests may be used to rule out systemic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis or infection, that can affect tendons. Markers like ESR and CRP can indicate inflammatory activity. - Synovial Fluid Analysis:

In cases of suspected tenosynovitis or bursitis, synovial fluid may be extracted and analyzed to check for infection, crystals, or inflammatory cells.

Biopsy and Histopathology

- Tendon Biopsy:

In rare cases where a definitive diagnosis is required, a small sample of tendon tissue can be biopsied and examined microscopically for degenerative changes, inflammation, or neoplastic processes.

Diagnostic Injections

- Anesthetic Injections:

Local anesthetic injections can temporarily relieve pain, confirming that the tendon is the source of discomfort. A positive response to corticosteroid injections can also indicate an inflammatory process.

Treatment Approaches for Tendon Disorders

Effective management of tendon disorders is highly individualized and often involves a combination of conservative measures, innovative therapies, and surgical interventions.

Conservative Management

Rest and Activity Modification

- Rest:

Minimizing use of the affected tendon is crucial to allow healing and reduce further damage. - Activity Modification:

Adjust activities to reduce repetitive strain on the tendon. Ergonomic changes and alternative exercises can help minimize stress.

Physical Therapy

- Strengthening Exercises:

Focused exercises, particularly eccentric training, help improve tendon resilience and promote proper collagen alignment. - Stretching:

Regular stretching of the affected tendon and surrounding muscles increases flexibility and reduces stiffness. - Manual Therapy:

Techniques such as massage and joint mobilization can help alleviate pain and improve range of motion.

Medications

- NSAIDs:

Over-the-counter or prescription NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce inflammation and relieve pain. - Topical Analgesics:

Gels or creams containing NSAIDs can be applied directly to the affected area for localized relief.

Injections

- Corticosteroid Injections:

When inflammation is significant, corticosteroid injections provide potent anti-inflammatory effects but should be used sparingly. - Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP):

PRP injections use the patient’s own concentrated platelets to promote healing through growth factors. This therapy is showing promise for chronic tendinopathies such as Achilles tendinosis.

Innovative Treatments

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (ESWT)

- Mechanism:

ESWT uses high-energy shock waves to stimulate tissue repair and reduce pain. - Applications:

Effective for chronic tendon conditions like plantar fasciitis and Achilles tendinopathy, ESWT can accelerate healing by promoting cellular regeneration.

Stem Cell Therapy

- Approach:

Stem cell therapy involves injecting stem cells into the damaged tendon to promote tissue regeneration. - Potential:

Although still in experimental stages, this therapy may offer a future solution for severe tendon injuries and degenerative conditions.

Surgical Interventions

Tendon Repair

- Procedure:

Surgical repair involves reattaching torn tendon ends or reconstructing damaged areas using sutures or grafts. - Indications:

Often required in cases of complete tendon rupture or severe tears that do not respond to conservative treatment.

Tendon Transfer

- Purpose:

Tendon transfer surgery involves redirecting a healthy tendon to replace the function of a damaged one. - Applications:

Commonly used when a tendon is irreparable, this procedure can restore function and improve mobility.

Debridement and Excision

- Procedure:

Removal of degenerated tendon tissue (debridement) or excision of calcific deposits can alleviate pain and promote healing. - Rehabilitation:

Postoperative physical therapy is essential to regain strength and flexibility.

Rehabilitation and Recovery

Physical Therapy

- Role:

Tailored rehabilitation programs are crucial to restoring tendon strength, flexibility, and functionality after injury or surgery. - Modalities:

Include exercises, manual therapy, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation to enhance recovery.

Gradual Return to Activity

- Guidelines:

A phased approach to returning to full activity helps prevent re-injury. Progressive loading and monitored exercise routines are key.

Effective Supplements for Tendon Health

Proper nutrition and targeted supplementation can enhance tendon repair, reduce inflammation, and support overall musculoskeletal health.

Vitamins and Minerals

- Vitamin C:

Essential for collagen synthesis, vitamin C supports tendon repair and protects connective tissue from oxidative damage. - Vitamin E:

Acts as a potent antioxidant, helping to reduce inflammation and protect tendon cells from oxidative stress. - Vitamin D:

Plays a role in calcium absorption and bone health, indirectly supporting tendon attachment and function. - Magnesium:

Important for muscle relaxation and nerve function, magnesium helps reduce muscle cramps that can strain tendons. - Zinc:

Supports protein synthesis and tissue repair, making it crucial for maintaining tendon integrity.

Herbal Supplements

- Turmeric (Curcumin):

With powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, curcumin can reduce tendon inflammation and promote healing. - Boswellia:

Known for its anti-inflammatory effects, Boswellia may help relieve pain associated with tendon disorders. - Ginger:

Its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties make ginger a beneficial supplement for reducing tendon pain and swelling.

Enzymes

- Bromelain:

Derived from pineapple, bromelain is known to reduce inflammation and facilitate tendon recovery. - Papain:

An enzyme from papaya, which may help with inflammation and aid in tissue repair.

Collagen Supplements

- Type I Collagen:

Collagen supplements provide the amino acids necessary for tendon repair and maintenance. - Hydrolyzed Collagen:

Easier to absorb, hydrolyzed collagen supports joint health and promotes the regeneration of connective tissue.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Fish Oil:

Rich in EPA and DHA, omega-3 fatty acids reduce inflammation and promote overall musculoskeletal health. - Flaxseed Oil:

A plant-based alternative that also helps reduce inflammation and supports tendon health.

Antioxidants

- Resveratrol:

This antioxidant found in grapes and berries helps protect tendon cells from oxidative stress. - Alpha-Lipoic Acid:

A potent antioxidant that reduces oxidative damage and promotes nerve and tendon health.

Amino Acids

- L-Theanine:

Known for its calming effects, L-theanine helps reduce stress that can contribute to tendon strain. - Acetyl-L-Carnitine:

Supports energy production in cells, including tenocytes, and has neuroprotective properties.

Lifestyle and Maintenance Tips for Tendon Health

Adopting healthy lifestyle habits is essential for maintaining tendon strength and preventing injuries. Here are some evidence-based practices to keep your tendons in top condition:

Warm-Up and Stretching

- Dynamic Warm-Up:

Engage in dynamic stretching before physical activity to prepare the tendons and muscles for movement. - Regular Stretching:

Incorporate both static and dynamic stretching routines into your daily regimen to maintain flexibility and reduce stiffness.

Strength Training and Conditioning

- Strengthening Exercises:

Target exercises that strengthen the muscles surrounding the tendons, thereby reducing the load on the tendons themselves. - Eccentric Training:

Eccentric exercises, where muscles lengthen under tension, are particularly effective in treating tendinopathy and improving tendon resilience.

Activity Modification and Recovery

- Avoid Overuse:

To prevent repetitive strain injuries, alternate between different types of physical activities and ensure adequate rest between workouts. - Proper Technique:

Always use correct form and technique during exercise to reduce the risk of tendon injuries. - Rest and Recovery:

Allow sufficient time for recovery after strenuous activities. Use techniques such as ice therapy, compression, and elevation to reduce inflammation after exercise.

Nutrition and Hydration

- Balanced Diet:

A diet rich in vitamins, minerals, and proteins supports tissue repair and overall tendon health. - Stay Hydrated:

Adequate water intake is essential for maintaining tissue elasticity and promoting efficient nutrient transport. - Avoid Processed Foods:

Reducing intake of processed and high-sugar foods helps minimize inflammation and supports overall musculoskeletal health.

Ergonomics and Posture

- Proper Ergonomics:

Use ergonomic tools and maintain good posture during work and daily activities to reduce undue stress on tendons. - Supportive Footwear:

Wear shoes that offer proper support and cushioning to protect tendons in the lower extremities, especially during high-impact activities.

Stress Management

- Mindfulness Practices:

Incorporate stress-reduction techniques such as meditation, yoga, or deep breathing exercises into your daily routine. Reducing overall stress can lower the risk of tendon tension and injury. - Adequate Sleep:

Aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep each night to facilitate recovery and overall musculoskeletal health.

Trusted Resources for Tendon Health

For those seeking additional information on tendon health, numerous reputable resources offer evidence-based insights and practical guidance.

Books

- “The Complete Guide to Tendon Health” by Dr. John A. Casey

An in-depth resource covering tendon anatomy, common injuries, and comprehensive treatment strategies. - “Tendon Injuries: Basic Science and Clinical Medicine” by Dr. Nicola Maffulli and Dr. Nicola Abate

A detailed examination of tendon pathology and modern approaches to treatment and rehabilitation. - “Tendinopathy: Diagnosis and Treatment” by Dr. Karim Khan

Offers a thorough overview of tendinopathy, including diagnosis, innovative treatment options, and rehabilitation protocols.

Academic Journals

- Journal of Orthopaedic Research:

Publishes high-quality research on musculoskeletal injuries, including studies on tendon repair and regeneration. - The American Journal of Sports Medicine:

Provides clinical studies, reviews, and evidence-based guidelines related to tendon injuries and sports medicine.

Mobile Applications

- MyFitnessPal:

Helps track nutritional intake and exercise routines to support overall musculoskeletal health. - Strava:

An app for athletes to track workouts and monitor physical activity, aiding in injury prevention and rehabilitation. - PhysiApp:

Offers personalized physical therapy exercises and rehabilitation programs for tendon and musculoskeletal injuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of tendons?

Tendons connect muscles to bones, transmitting the force generated by muscle contractions to produce movement. They also provide joint stability and serve as elastic energy storage units during dynamic activities.

How do tendons adapt to mechanical load?

Tendons adapt through mechanotransduction, where mechanical stimuli lead to cellular responses that strengthen the collagen matrix and improve the tendon’s ability to withstand stress.

What causes tendinitis and tendinosis?

Tendinitis is typically caused by acute overuse or injury leading to inflammation, while tendinosis is a chronic degenerative condition resulting from repetitive strain and inadequate healing.

How are tendon injuries diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a combination of patient history, physical examination, and imaging studies such as ultrasound or MRI. Functional tests and, in some cases, biopsies help confirm the extent and nature of the injury.

What treatments are available for tendon disorders?

Treatment options range from conservative measures—such as rest, physical therapy, and medications—to innovative therapies like PRP injections, ESWT, and surgical interventions like tendon repair or transfer.

Disclaimer & Sharing

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for diagnosis and treatment tailored to your individual needs.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social platform to help spread awareness and promote tendon health.