What is scleritis?

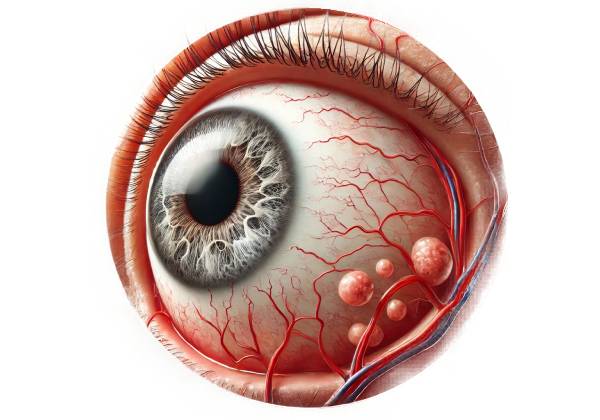

Scleritis is a serious and potentially blinding inflammatory condition affecting the sclera, the white outer coat of the eye. Unlike more superficial eye inflammations, such as episcleritis, scleritis affects deeper layers of the sclera and, if untreated, can cause significant pain, redness, and vision loss. This condition is frequently associated with systemic autoimmune diseases, but it can also develop on its own or as a result of infections or trauma. Understanding scleritis necessitates an examination of the eye’s anatomy, the various types of scleritis, potential causes, and the clinical manifestations that set this condition apart.

Anatomy and Function of the Sclera

The sclera is a thick, fibrous tissue that serves as the eye’s protective outer layer, covering the majority of its surface. It is continuous with the cornea in the front of the eye and is primarily made up of collagen and elastin fibers, which give the eye its strength and rigidity. The sclera not only keeps the eyeball in shape, but it also acts as an attachment point for the extraocular muscles that control eye movement. The episclera (the outermost layer), the stroma (the middle, thickest layer), and the lamina fusca (the innermost layer) make up the sclera.

In scleritis, inflammation can affect one or more of these layers, resulting in varying degrees of severity and clinical manifestation. Because of its proximity to the underlying uveal tract (which includes the iris, ciliary body, and choroid) and the optic nerve, scleritis can have a significant impact on both the anterior and posterior segment structures of the eye.

Classification of Scleritis

The anatomical location of the inflammation and the severity of the condition determine the classification of scleritis. The major classifications include:

- Anterior Scleritis is the most common type of scleritis, accounting for the vast majority of cases. Anterior scleritis affects the front part of the sclera and is further classified into the following subtypes:

- Diffuse Anterior Scleritis: This subtype is characterized by widespread inflammation across the anterior sclera, resulting in uniform redness and swelling. It is typically the least severe and responds well to treatment.

- Nodular Anterior Scleritis: This subtype is characterized by localized inflammation that forms distinct, tender nodules on the sclera. These nodules are immobile and can be extremely painful.

- Necrotizing Anterior Scleritis with Inflammation: This is the most severe type of anterior scleritis, characterized by excruciating pain and avascular, necrotic areas where scleral tissue is being destroyed. If not treated promptly, this form can result in serious complications, including vision loss.

- Necrotizing Anterior Scleritis without Inflammation (Scleromalacia Perforans): This uncommon type of necrotizing scleritis causes little or no pain and is most commonly seen in patients with long-standing autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. The sclera thins gradually and without visible inflammation, potentially leading to perforation.

- Posterior Scleritis: Because it affects the back of the sclera, posterior scleritis is less common and can be more difficult to diagnose. It can result in serious complications such as retinal detachment, choroidal folds, and optic nerve swelling. Unlike anterior scleritis, posterior scleritis may not cause visible redness of the eye, making it difficult to diagnose without imaging studies.

Pathophysiology of Scleritis

The pathophysiology of scleritis is characterized by an immune-mediated inflammatory process targeting scleral tissue. The precise mechanisms vary depending on the underlying cause, but in many cases, immune complexes are deposition in the sclera, causing complement activation and the recruitment of inflammatory cells such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. These cells produce a wide range of cytokines and enzymes, which contribute to tissue damage, vasculitis, and disease symptoms.

In necrotizing scleritis, the inflammatory process is especially aggressive, causing scleral tissue destruction and the formation of necrotic, avascular areas. This severe form of scleritis is frequently associated with systemic vasculitic diseases like granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis) or polyarteritis nodosa, necessitating immediate medical attention to avoid complications.

Etiology and Related Systemic Disorders

Scleritis can occur as a standalone ocular condition, but it is frequently associated with systemic autoimmune disorders. Understanding the etiology is critical for effective management, as treating the underlying systemic condition frequently reduces ocular inflammation.

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common systemic disease associated with scleritis, particularly the necrotizing type. In RA, the immune system attacks synovial tissues, causing chronic inflammation and joint damage. This same autoimmune process can affect the sclera, resulting in severe scleritis.

- Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (GPA): Previously known as Wegener’s granulomatosis, GPA is a type of vasculitis affecting small to medium-sized blood vessels. GPA frequently causes ocular involvement, and scleritis is a common manifestation, often presenting as necrotizing scleritis.

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a multisystem autoimmune disease that can affect any organ in the body, including the eyes. Scleritis is less common in SLE patients than in RA, but it can still occur, especially in those with active systemic inflammation.

- Ankylosing Spondylitis: This chronic inflammatory disease primarily affects the spine and sacroiliac joints, but can also affect the eyes, causing scleritis. Ocular involvement in ankylosing spondylitis is most commonly seen as uveitis, but scleritis can also occur, especially in severe cases.

- Relapsing Polychondritis is a rare autoimmune disease that affects body cartilage, including the ears, nose, and respiratory tract. Scleritis is a type of ocular inflammation that frequently coexists with episcleritis and uveitis.

- Infectious Causes: Although uncommon, infections can cause scleritis. Bacterial infections, particularly those involving Pseudomonas aeruginosa, are a well-known cause, especially after surgery or trauma. Fungal, viral, and parasitic infections can also cause scleritis, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

- Trauma and Surgery: Ocular trauma, such as blunt or penetrating injuries, can cause scleritis, especially if there is an associated infection. Scleritis can also develop as a complication of eye surgery, such as cataract extraction or scleral buckle procedures for retinal detachment.

- Idiopathic Scleritis: When there is no underlying cause, the condition is known as idiopathic scleritis. Even in these cases, a thorough evaluation is required to rule out any underlying systemic diseases.

Clinical Presentation

Scleritis causes a variety of symptoms, which can differ in severity depending on the type and location of the inflammation. The hallmark symptoms include:

- Severe Ocular Pain: Scleritis pain is often described as deep, boring, and intense. It frequently radiates to the forehead, brow, or jaw, and eye movement exacerbates it. The pain is usually worse in necrotizing forms of scleritis, which distinguishes it from episcleritis, which is less painful.

- Redness: Scleritis causes a deep, violaceous redness of the eye, especially in the anterior forms. The dilation of the deep episcleral vessels, as well as the underlying inflammation, cause this redness. Nodular scleritis is distinguished by discrete, raised nodules, whereas diffuse scleritis is characterized by more generalized redness and swelling.

- Visual Disturbances: Scleritis can impair visual acuity, especially if the inflammation spreads to the cornea, retina, or optic nerve. Patients may report blurred vision, reduced visual acuity, or, in severe cases, sudden vision loss.

- Photophobia and Tearing: Light sensitivity (photophobia) and increased tearing are common symptoms, particularly in anterior scleritis, which may also affect the cornea.

- Headache and Systemic Symptoms: Some patients with scleritis may have headaches, especially if the inflammation spreads to the orbit or affects the optic nerve. Systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and fatigue may also occur, especially in those who have associated systemic autoimmune diseases.

Complications

Scleritis, especially the necrotizing forms, can cause serious complications if not treated promptly. This includes:

- Scleral Thinning and Perforation: Chronic inflammation can thin the sclera, increasing the risk of scleral perforation. This is especially true for necrotizing scleritis, which causes tissue destruction.

- Keratitis and Corneal Ulcers: Inflammation in the sclera can spread to the cornea, causing keratitis and corneal ulcers. This can cause scarring and significant vision loss.

- Uveitis and Glaucoma: Scleritis can cause secondary uveitis, especially in the anterior segment. In severe cases, inflammation can also affect the trabecular meshwork, resulting in increased intraocular pressure and secondary glaucoma. Glaucoma is a potentially blinding complication that requires immediate treatment to avoid optic nerve damage.

- Retinal Detachment and Choroidal Detachment: Posterior scleritis can cause exudative retinal or choroidal detachments, which can impair vision. These detachments occur when fluid accumulates under the retina or choroid as a result of inflammation.

- Optic Neuropathy: When scleritis affects the posterior part of the eye, the optic nerve can become involved, resulting in optic neuropathy. This can manifest as loss of color vision, decreased visual acuity, or visual field defects, and if not treated, it can result in permanent vision loss.

- Orbital Involvement: Scleritis can sometimes spread to the orbit, causing inflammation (orbital cellulitis) and resulting in proptosis (eye bulging), diplopia (double vision), and restricted eye movements. Orbital involvement is a serious complication that can jeopardize the patient’s vision as well as his or her general health.

Prognosis

The prognosis of scleritis is heavily dependent on the type of scleritis, the underlying cause, and the timing of treatment. Diffuse anterior scleritis typically has a better prognosis, especially if diagnosed early and treated properly. Nodular scleritis can also be treated successfully if caught early on.

Necrotizing scleritis has a poor prognosis, particularly when combined with systemic autoimmune diseases, due to the risk of severe complications such as scleral perforation, corneal involvement, and vision loss. The prognosis for posterior scleritis varies according to the severity of posterior segment involvement and the presence of associated complications such as retinal detachment or optic neuropathy.

Overall, early diagnosis and treatment are critical in preventing disease progression and reducing the risk of permanent visual impairment.

Diagnostic Approaches for Scleritis

Scleritis diagnosis requires a thorough approach that includes a detailed patient history, clinical examination, and a battery of diagnostic tests. These methods aid in confirming the diagnosis, distinguishing scleritis from other similar conditions, and determining the extent of inflammation and its impact on surrounding ocular structures.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing scleritis is a thorough clinical examination, which usually includes the following components:

- Visual Acuity Test: Measuring visual acuity is critical for determining the impact of the inflammation on the patient’s vision. Any decrease in visual acuity, especially in posterior scleritis, may indicate involvement of the cornea, retina, or optic nerve.

- Slit-Lamp Examination: A slit-lamp examination provides a thorough examination of the anterior segment of the eye, including the sclera, episclera, and cornea. The examination may reveal the presence of scleral redness, nodules, or necrosis. It also aids in distinguishing scleritis from episcleritis, a less severe inflammation that only affects the sclera’s superficial layers.

- Fundus Examination: A fundus examination is required in cases of suspected posterior scleritis. This examination, which is frequently performed with indirect ophthalmoscopy, can reveal evidence of posterior segment involvement, such as optic disc swelling, retinal detachment, or choroidal folds.

Imaging Studies

Imaging studies are frequently required to confirm the diagnosis of scleritis, especially when posterior scleritis is suspect. The studies include:

- Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM): UBM is a high-resolution ultrasound technique that provides detailed imaging of the eye’s anterior segment, including the sclera. It can assist in visualizing scleral thickening, detecting nodules, and determining the extent of inflammation.

- B-Scan Ultrasonography: B-scan ultrasonography is especially effective at detecting posterior scleritis. It can reveal specific findings such as scleral thickening, fluid in the Tenon’s capsule (T-sign), and posterior segment complications such as retinal detachment or optic disc swelling.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining cross-sectional images of the retina and choroid. It is useful for detecting macular edema, choroidal folds, and subretinal fluid, all of which can be associated with posterior scleritis.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI can help determine the extent of orbital involvement in severe cases of scleritis. It provides detailed images of the orbital tissues, optic nerve, and extraocular muscles that are susceptible to inflammation.

Lab Tests

Laboratory tests are frequently used to detect any underlying systemic disease associated with scleritis. These tests can include:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): A CBC can detect signs of systemic inflammation, such as a high white blood cell count, which could indicate an infectious or autoimmune process.

- Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP): Both are indicators of systemic inflammation. Elevated levels of these markers may indicate an active inflammatory or autoimmune process, which is common in patients with scleritis.

- Autoantibody Testing: Specific autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) for rheumatoid arthritis, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) for granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or antinuclear antibodies (ANA) for systemic lupus erythematosus, can help identify underlying autoimmune diseases associated with scleritis.

- Infectious Workup: To identify the causative agent of scleritis, appropriate cultures, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, or serology tests for pathogens such as bacteria, fungi, or viruses may be required.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiating scleritis from other ocular conditions is critical for effective treatment. Key conditions to consider are:

- Episcleritis: A more superficial and less severe inflammation of the episclera, episcleritis is typically less painful and does not result in scleral necrosis or significant visual impairment. Episcleritis typically resolves on its own or with minimal treatment.

- Keratitis: Inflammation of the cornea, keratitis can cause pain and redness but is usually associated with corneal changes such as ulceration or opacification, which are not present in isolated scleritis.

- Uveitis: Inflammation of the uveal tract, uveitis can coexist with scleritis, but it usually affects the iris, ciliary body, or choroid, resulting in various clinical signs such as posterior synechiae, anterior chamber cells, and flare.

- Orbital Cellulitis: A bacterial infection of the orbital tissues, orbital cellulitis can cause similar symptoms of pain, redness, and proptosis, but it is frequently accompanied by systemic signs of infection, such as fever and leukocyte count.

- Retinal Detachment: When posterior scleritis is associated with retinal detachment, it is critical to identify the underlying cause. Retinal detachment without scleral inflammation would not cause the same level of pain or scleral involvement.

Best Practices for Scleritis Management

Scleritis treatment is multifaceted, with the goal of not only controlling inflammation and relieving symptoms, but also addressing any underlying systemic disease that may be contributing to the condition. Because of the potential severity and risk of complications associated with scleritis, treatment frequently necessitates a collaborative effort involving both ophthalmologists and rheumatologists, or other specialists, depending on the underlying cause. Here are the primary strategies for managing scleritis:

Medical Management

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- For mild to moderate scleritis, particularly diffuse anterior scleritis, NSAIDs are frequently the first line of treatment. Ibuprofen, indomethacin, and naproxen can all help with pain and inflammation. NSAIDs may be effective as monotherapy in cases where inflammation is mild and there is no underlying systemic disease. If the response is inadequate, NSAIDs may need to be administered in higher doses or combined with other therapies.

- Corticosteroids:

- Systemic corticosteroids are the primary treatment for more severe forms of scleritis, particularly nodular, necrotizing, and posterior scleritis. Prednisone is commonly used, typically beginning with a high dose (e.g., 1 mg/kg per day) and gradually tapering based on clinical response. Corticosteroids are effective at quickly reducing inflammation and pain, but their use should be carefully monitored due to potential side effects such as weight gain, osteoporosis, and an increased risk of infection.

- Local corticosteroid injections may be used in certain cases, particularly for nodular scleritis. However, this approach is typically reserved for situations in which systemic therapy is either contraindicated or insufficient.

- Agents that suppress the immune system

- Immunosuppressive therapy is frequently required for patients with severe, recurrent, or necrotizing scleritis, especially those with an underlying systemic autoimmune disorder. Methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide are common anti-inflammatory medications that reduce the need for long-term corticosteroid use. These medications work by inhibiting the immune response that causes the inflammatory process in scleritis.

- Biologic agents, such as infliximab or rituximab, may be considered in cases of scleritis associated with autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or granulomatosis with polyangiitis when conventional immunosuppressive therapy is ineffective. These biologics target specific immune system components, providing more targeted therapy while potentially having fewer side effects than broad immunosuppressants.

- Antibiotics and antimicrobials:

- If scleritis is caused by an infectious agent, such as bacteria, fungi, or viruses, proper antimicrobial treatment is required. The pathogen and its susceptibility profile will influence the choice of antibiotic or antiviral medication. In some cases, especially with severe infections, intravenous antibiotics or antifungals may be necessary in addition to topical treatments.

Surgical Management

While medical management is the primary approach to treating scleritis, surgical intervention may be required in certain cases, particularly when complications arise:

- Scleral Grafting:

- Scleral grafting may be necessary in cases of necrotizing scleritis with significant scleral thinning or a risk of perforation. This procedure involves transplanting healthy scleral tissue, usually from a donor, to strengthen the weakened area and prevent further complications. Scleral grafting is a specialised procedure that is usually carried out by an ophthalmic surgeon with experience in corneal and external eye diseases.

- Retina Detachment Repair:

- If posterior scleritis causes retinal detachment, surgical intervention may be required to reattach the retina. Depending on the type and severity of the detachment, techniques such as pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckling, or vitrectomy may be required. In these cases, prompt surgical treatment is critical for preserving vision.

- Treatment for Secondary Glaucoma

- Scleritis can cause secondary glaucoma due to inflammation or corticosteroid use. In such cases, surgical procedures to reduce intraocular pressure, such as trabeculectomy or implantation of a glaucoma drainage device, may be required.

Treatment of Underlying Systemic Disease

Because scleritis is frequently associated with systemic autoimmune conditions, controlling the underlying disease is an essential part of treatment. This usually entails working with a rheumatologist or another specialist who can address the systemic disease holistically. Effective underlying condition management not only improves scleritis control but also lowers the risk of recurrence and long-term complications.

Monitoring and Follow-up

Patients with scleritis, especially those on long-term immunosuppressive therapy, require regular follow-up visits. Monitoring includes assessing treatment response, adjusting medications as needed, and screening for potential therapy side effects. Patients should be educated on the warning signs of complications, such as worsening pain, vision changes, or increased redness, and advised to seek immediate medical attention if they occur.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Clinical Ophthalmology: A Systematic Approach” by Jack J. Kanski and Brad Bowling: This textbook provides comprehensive information on the diagnosis and management of scleritis and other ocular conditions.

- “Ocular Pathology” by Myron Yanoff and Joseph W. Sassani: A detailed resource on the pathological aspects of eye diseases, including scleritis, offering in-depth insights into the condition’s histopathology.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO offers extensive resources for both patients and professionals, including guidelines on the diagnosis and management of scleritis.

- The Scleritis Foundation: This organization provides support and information for individuals affected by scleritis, including access to research and patient education materials.

- National Eye Institute (NEI): Part of the NIH, the NEI offers reliable information on eye conditions, including scleritis, and supports research in ophthalmology.