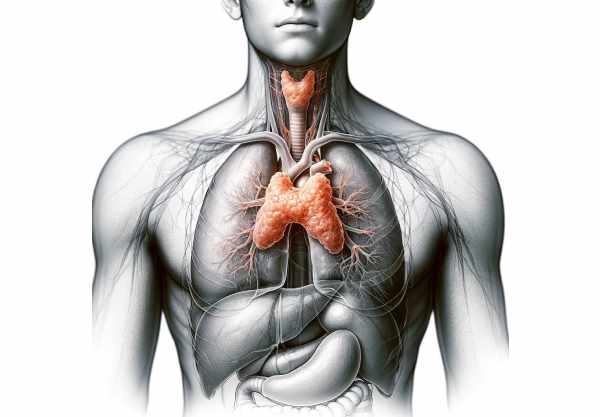

The thymus is a small, yet critically important, organ located in the upper chest, playing a central role in the development and regulation of the immune system. Responsible for the maturation of T lymphocytes, the thymus establishes immune tolerance and helps prevent autoimmune reactions. In early life, it is highly active, but it gradually shrinks with age—a process known as involution—while still maintaining immune memory. This guide explores the thymus’s intricate anatomy, physiological functions, common disorders, diagnostic methods, treatment strategies, and practical tips to support overall immune health and well-being.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Architecture

- Lobular Organization

- Thymic Microenvironment

- Vascular Supply, Innervation & Lymphatics

- Development & Involution

- Physiology and Immune Functions

- Common Thymic Disorders

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Treatment Strategies

- Supplemental & Nutritional Support

- Lifestyle & Preventative Practices

- Trusted Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Disclaimer & Sharing

Anatomical Architecture

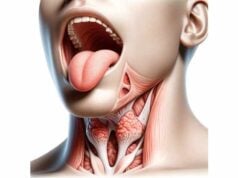

The thymus is a bilobed organ situated in the anterior superior mediastinum, just behind the sternum and above the heart. Each lobe is encapsulated in a thin fibrous capsule that sends septa into the organ, dividing it into many small lobules. These lobules are the basic functional units and contain two distinct regions—the outer cortex and the inner medulla—that provide the specialized environment needed for T cell maturation. Although the thymus is most prominent during childhood and adolescence, its structure continues to influence immune function throughout life, even as it gradually undergoes involution with age.

Lobular Organization

Within the thymus, the formation of lobules is essential for its immune functions. The fibrous septa of the capsule divide each lobe into multiple lobules, each consisting of an outer cortex and an inner medulla.

- Cortex:

The outer region, densely packed with immature T cells (thymocytes), forms a vibrant, dark-staining area. Cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) provide structural support and secrete essential cytokines, such as interleukin-7 (IL-7), to promote thymocyte proliferation and differentiation. - Medulla:

The inner region is lighter in appearance and houses more mature T cells. Medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) and specialized structures known as Hassall’s corpuscles play pivotal roles in the process of negative selection, eliminating self-reactive T cells and establishing central tolerance.

This compartmentalization is crucial, as it allows the thymus to rigorously screen developing T cells, ensuring that only those with appropriate self-tolerance enter the peripheral circulation.

Thymic Microenvironment

The thymic microenvironment is a complex network of cells and extracellular components that orchestrates the delicate process of T cell development. This environment is composed of:

- Thymic Epithelial Cells (TECs):

Both cortical and medullary TECs create a scaffold that supports thymocyte development and provide essential signals for survival, differentiation, and selection. They express a diverse range of self-antigens to aid in the elimination of autoreactive T cells. - Extracellular Matrix (ECM):

The ECM, made up of proteins such as collagen, fibronectin, and laminin, forms a supportive framework that facilitates cell adhesion, migration, and communication among thymocytes and stromal cells. - Cytokines and Chemokines:

Molecules such as IL-7, thymosin, and thymopoietin are secreted within the thymic milieu. They are critical for promoting thymocyte survival, proliferation, and differentiation, while also guiding the migration of cells between the cortex and medulla. - Hassall’s Corpuscles:

These unique structures, found within the medulla, are thought to play a role in the maturation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and in the clearance of apoptotic cells, further ensuring immune tolerance.

This finely tuned microenvironment is essential for the thymus to perform its central role in establishing a competent and self-tolerant T cell repertoire.

Vascular Supply, Innervation & Lymphatics

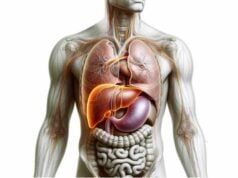

The thymus is well supported by a network of blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatic channels that facilitate nutrient delivery, waste removal, and immune cell trafficking.

Vascular Supply

- Arterial Input:

The thymus receives blood from the internal thoracic (mammary) arteries, which branch off the subclavian arteries. This robust arterial supply ensures that the thymic tissue receives adequate oxygen and essential nutrients for T cell development. - Venous Drainage:

Venous blood is collected via thymic veins, which drain into the left brachiocephalic vein, eventually entering the superior vena cava. This efficient drainage is critical for the removal of metabolic waste products from the thymus.

Innervation

- Autonomic Innervation:

The thymus is innervated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. Sympathetic nerves from the cervical and upper thoracic ganglia modulate thymic function and blood flow, while parasympathetic fibers contribute to its regulation. - Neural Regulation:

This dual autonomic control influences thymic hormone secretion and overall cellular activity within the organ.

Lymphatic Drainage

- Lymphatic Vessels:

Although the thymus lacks afferent lymphatic vessels (reflecting its primary role in T cell development rather than lymph filtration), it has an extensive network of efferent lymphatic channels. - Lymph Node Connection:

Lymph from the thymus drains into the anterior mediastinal and parasternal lymph nodes, aiding in the migration of mature T cells into the peripheral circulation.

Development and Involution

The thymus is most active during childhood and adolescence, undergoing significant changes throughout life.

Development

- Fetal Stage:

The thymus begins to develop early in fetal life from the third to fifth week, originating from the third pharyngeal pouch. By mid-gestation, the thymus is fully formed and starts to produce T cells. - Postnatal Growth:

After birth, the thymus continues to grow and function robustly, reaching its maximum size and activity during puberty. This period is crucial for establishing a diverse and self-tolerant T cell repertoire.

Involution

- Age-Related Decline:

Following puberty, the thymus gradually shrinks in a process known as involution. By middle age, much of the thymic tissue is replaced by adipose tissue, resulting in a decreased output of naive T cells. - Impact on Immunity:

Although thymic involution contributes to a reduced capacity to respond to new antigens, the immune system is partly maintained by memory T cells and peripheral proliferation of existing T cells.

Despite involution, the thymus continues to play a role in immune regulation, and strategies to preserve or even rejuvenate thymic function are active areas of research.

Physiology and Immune Functions

The thymus is central to the development and maturation of T lymphocytes, essential players in the adaptive immune system. Its physiological processes include several key stages:

T-Cell Development

- Origin of Thymocytes:

Immature T cells, known as thymocytes, migrate from the bone marrow to the thymus, where they undergo a rigorous developmental process. - Proliferation and Differentiation:

In the cortical region, thymocytes proliferate rapidly and begin to express T cell receptors (TCRs). They are then subjected to positive and negative selection to ensure that only T cells capable of recognizing self-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules—and not reacting strongly to self-antigens—survive.

Positive Selection

- Process:

Thymocytes in the cortex interact with cortical thymic epithelial cells (cTECs) that present self-peptides on MHC molecules. Thymocytes with TCRs that can recognize these complexes receive survival signals. - Outcome:

This process ensures that the emerging T cells are capable of recognizing antigens when presented by MHC molecules in peripheral tissues.

Negative Selection

- Mechanism:

In the medulla, thymocytes are exposed to a broader range of self-antigens presented by medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) and dendritic cells. Those thymocytes that bind too strongly to self-antigens undergo apoptosis. - Significance:

Negative selection is crucial for the establishment of central tolerance, preventing autoimmunity by eliminating self-reactive T cells before they enter the circulation.

Thymic Hormones

- Thymosin and Thymopoietin:

The thymus produces several hormones that influence T cell development and differentiation. Thymosin helps stimulate T cell maturation, while thymopoietin plays a role in T cell differentiation and neuromuscular regulation. - Thymulin:

Thymulin modulates immune responses and influences the secretion of other hormones involved in T cell development.

Role in Immunological Memory

While the thymus’s primary function is to generate a diverse pool of T cells during early life, it also indirectly contributes to immunological memory by shaping the T cell repertoire. Mature, self-tolerant T cells circulate in the body and provide long-term immune protection against previously encountered pathogens.

Common Disorders of the Thymus

Several disorders can affect the thymus, ranging from benign conditions to malignant tumors. These conditions can impact immune function and overall health.

Thymic Hyperplasia

- Definition:

Thymic hyperplasia is characterized by an abnormal enlargement of the thymus, often due to an increase in thymic cells or lymphoid tissue. - Associated Conditions:

Frequently seen in autoimmune diseases like myasthenia gravis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and rheumatoid arthritis. - Clinical Impact:

While often benign, thymic hyperplasia can contribute to immune dysregulation and may necessitate further evaluation.

Thymomas

- Nature:

Thymomas are tumors arising from the epithelial cells of the thymus. They are the most common thymic neoplasms and may be benign or malignant. - Subtypes:

Classified into several types (Type A, AB, B1, B2, and B3) based on the cellular composition and morphology. - Clinical Associations:

Thymomas are often associated with paraneoplastic syndromes, particularly myasthenia gravis, and require careful diagnosis and management.

Thymic Carcinomas

- Characteristics:

Thymic carcinomas are aggressive malignant tumors that arise from thymic tissue. They are less common than thymomas but have a poorer prognosis. - Management:

Treatment typically involves a combination of surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

DiGeorge Syndrome

- Definition:

A congenital disorder resulting from a 22q11.2 deletion, leading to thymic hypoplasia or aplasia. - Consequences:

Severe immunodeficiency due to a lack of T cell production, along with congenital heart defects and facial anomalies. - Treatment:

Management includes immunoglobulin replacement therapy, prophylactic antibiotics, and, in some cases, thymus transplantation or surgical interventions.

Thymic Cysts

- Nature:

Thymic cysts are fluid-filled sacs within the thymus. They are typically benign and are often discovered incidentally during imaging. - Clinical Relevance:

Although usually asymptomatic, large or symptomatic cysts may require surgical removal.

Myasthenia Gravis

- Association:

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder that is strongly linked with thymic abnormalities, such as thymic hyperplasia or thymomas. - Impact:

The thymus in these patients often exhibits structural changes that contribute to the production of autoantibodies against acetylcholine receptors, leading to muscle weakness. - Treatment:

Management involves medications, thymectomy, and supportive therapies to improve neuromuscular transmission.

Thymic Involution

- Process:

With age, the thymus gradually undergoes involution, where active thymic tissue is replaced by adipose tissue. - Effects:

This natural decline in thymic function contributes to a reduced output of naive T cells, which can impact immune responses in older individuals.

Diagnostic Approaches

An accurate diagnosis of thymic disorders involves a combination of clinical evaluations, imaging studies, laboratory tests, and sometimes genetic analysis or biopsy.

Clinical Evaluation

- History and Physical Exam:

A comprehensive medical history and physical examination are essential. Symptoms such as chest pain, respiratory issues, muscle weakness, or signs of autoimmune disorders (e.g., myasthenia gravis) guide the diagnostic process. - Self-Reporting:

Patient self-reports of fatigue, recurrent infections, or other systemic symptoms may also provide clues.

Imaging Techniques

- Chest X-ray:

Often used as an initial screening tool to detect mediastinal masses or thymic enlargement, though it has limited sensitivity. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT scans are the gold standard for evaluating thymic pathology, providing detailed images of the thymus, its structure, and any associated masses or cysts. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI is useful for differentiating tissue types and assessing the extent of thymic tumors. It offers excellent soft tissue contrast without ionizing radiation. - Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan:

PET/CT scans assess metabolic activity, which is particularly useful in staging thymic malignancies and monitoring treatment response.

Laboratory Tests

- Autoantibody Panels:

Testing for anti-acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibodies and anti-MuSK antibodies helps diagnose myasthenia gravis. - Complete Blood Count (CBC) and Inflammatory Markers:

CBC, ESR, and CRP can help assess for systemic inflammation and underlying immune disorders. - Hormonal Assessments:

Though not routinely used, thymic hormone levels (e.g., thymosin, thymulin) can provide insight into thymic function.

Biopsy and Histopathological Examination

- Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) or Core Needle Biopsy:

These minimally invasive techniques are used to obtain tissue samples from thymic masses for cytological or histopathological analysis. - Surgical Biopsy:

In cases where less invasive methods are inconclusive, a surgical biopsy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) may be performed.

Genetic Testing

- FISH and CGH:

Genetic tests such as Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) and Comparative Genomic Hybridization (CGH) can detect chromosomal abnormalities like the 22q11.2 deletion seen in DiGeorge syndrome.

Functional Assessments

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs):

In cases where thymic masses impact lung function, PFTs can help evaluate the respiratory effects. - Electromyography (EMG):

EMG may be used in patients with myasthenia gravis to assess neuromuscular transmission.

Treatment Strategies

The management of thymic disorders depends on the specific condition, its severity, and the patient’s overall health. Treatment may involve a combination of medical management, surgical intervention, and supportive therapies.

Medical Management

Pharmacologic Treatments

- Corticosteroids:

Used to reduce inflammation and suppress the immune system in autoimmune conditions such as myasthenia gravis. - Immunosuppressants:

Medications like azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine help control autoimmune reactions associated with thymic abnormalities. - Cholinesterase Inhibitors:

Agents such as pyridostigmine improve neuromuscular transmission in patients with myasthenia gravis. - Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) and Plasmapheresis:

These therapies are used in severe autoimmune conditions to reduce the circulating autoantibodies and alleviate symptoms.

Surgical Interventions

Thymectomy

- Indications:

Thymectomy is commonly performed for thymomas, thymic carcinomas, and in some cases of myasthenia gravis. Removing the thymus can alleviate symptoms and, in certain autoimmune conditions, improve neuromuscular function. - Techniques:

- Transsternal Thymectomy: Involves a vertical incision through the sternum to provide direct access.

- Video-Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS): A minimally invasive technique that reduces recovery time and postoperative pain.

- Robotic-Assisted Thymectomy: Offers enhanced precision and improved surgical outcomes.

Radiation and Chemotherapy

- Radiation Therapy:

Often used as an adjuvant treatment post-thymectomy, especially in thymic malignancies, to eradicate residual cancer cells. - Chemotherapy:

Used in advanced or aggressive thymic carcinomas, chemotherapy agents such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide are commonly administered.

Emerging and Experimental Treatments

- Targeted Therapy:

New drugs targeting specific molecular pathways in thymic tumors are being investigated to improve outcomes with fewer side effects. - Immunotherapy:

Checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, are under investigation for thymic carcinomas, offering a new avenue for treatment. - Gene Therapy and Stem Cell Approaches:

Research into gene therapy and stem cell treatments holds promise for congenital thymic disorders and for rejuvenating thymic function in immunodeficient states.

Supplemental & Nutritional Support for Thymus Health

Optimal thymic function is closely tied to overall immune health. Several supplements can help bolster thymic health, promote T cell development, and reduce inflammation.

Vitamins and Minerals

- Vitamin D:

Essential for immune regulation and T cell function, vitamin D supplementation can be beneficial for individuals with low levels. - Zinc:

Supports T cell development and overall immune function, zinc is crucial for maintaining the integrity of thymic tissue. - Vitamin C:

An antioxidant that supports the immune system and protects thymic cells from oxidative damage. - Selenium:

Important for the activity of antioxidant enzymes, selenium helps protect the thymus and other immune cells from oxidative stress.

Herbal Supplements

- Ashwagandha:

An adaptogen known for reducing stress and modulating the immune response, supporting overall thymic health. - Turmeric (Curcumin):

With potent anti-inflammatory properties, curcumin can help reduce chronic inflammation that may affect thymic function. - Green Tea Extract:

Rich in catechins, green tea extract offers antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits that support immune health.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Fish Oil and Flaxseed Oil:

These omega-3 fatty acids reduce systemic inflammation and promote a balanced immune response, indirectly supporting thymic function.

Antioxidants

- Alpha-Lipoic Acid:

A powerful antioxidant that protects thymic cells from oxidative stress and supports cellular energy production. - Resveratrol:

Found in grapes and berries, resveratrol contributes to reduced inflammation and improved immune cell function.

Lifestyle & Preventative Practices for Thymus Health

A healthy thymus is vital for a robust immune system. Adopting good lifestyle habits can help maintain thymic function and overall immune health.

Diet and Nutrition

- Balanced Diet:

Consume a variety of nutrient-rich foods, including fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains, to support immune function and thymic health. - Hydration:

Adequate water intake is essential for cellular function and nutrient transport. - Antioxidant-Rich Foods:

Foods high in antioxidants, such as berries, nuts, and green leafy vegetables, can help reduce oxidative stress on thymic cells.

Physical Activity

- Regular Exercise:

Engaging in moderate physical activity improves circulation, reduces stress, and supports overall immune function. - Consistency:

Regular exercise helps maintain a balanced immune system, which is critical for sustaining thymic output.

Stress Management

- Mindfulness and Meditation:

Techniques such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, and deep breathing exercises reduce stress hormones and support thymic function. - Adequate Sleep:

Aim for 7–9 hours of quality sleep per night to allow the body to repair and maintain immune function. - Relaxation Techniques:

Incorporate practices that promote relaxation and lower cortisol levels, as chronic stress can impair thymic function.

Weight Management and Toxin Avoidance

- Healthy Weight:

Maintaining a healthy weight reduces systemic inflammation and supports overall immune health. - Reduce Toxin Exposure:

Avoid environmental toxins and chemicals that can impair immune function by choosing organic foods and using natural personal care products.

Regular Health Check-Ups

- Preventive Care:

Regular medical check-ups help detect early signs of thymic or immune-related disorders, allowing for timely intervention. - Vaccinations and Screenings:

Keeping up with recommended vaccinations and routine health screenings supports overall immune health.

Trusted Resources for Thymus Health

For further information and the latest research on thymus health, consider the following reputable resources:

Books

- “Immunology: A Short Course” by Richard Coico and Geoffrey Sunshine

A clear and concise introduction to immunology, including detailed sections on the thymus and its role in T cell development. - “Thymus Gland Pathology: Clinical, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Features” by Corrado Lavini and Franco Cavalli

Offers an in-depth exploration of thymic disorders, diagnostic methods, and treatment strategies. - “The Immune System” by Peter Parham

Provides a comprehensive overview of immune system function, with a focus on thymic development and T cell maturation.

Academic Journals

- Journal of Clinical Investigation

Publishes high-quality research articles on immunology and thymic function. - Thymus

A specialized journal dedicated to research on the thymus, covering both basic science and clinical applications.

Mobile Apps

- MyImmuneCoach:

Provides personalized information and tracking tools for immune health, including features related to thymic function. - Immune Health Tracker:

An app designed to help users monitor their overall immune status and adopt lifestyle changes that support immune system function.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of the thymus?

The thymus is responsible for the maturation of T cells, a critical process for the development of the adaptive immune system and the establishment of central tolerance, which prevents autoimmunity.

How does the thymus contribute to immune tolerance?

Within the thymus, T cells undergo positive and negative selection. This process ensures that only T cells that properly recognize self-MHC molecules without reacting strongly to self-antigens are released into circulation, thus establishing immune tolerance.

What is thymic involution?

Thymic involution is the age-related shrinkage and replacement of active thymic tissue with adipose tissue. Although this reduces the output of naive T cells, memory T cells and peripheral expansion help maintain immunity.

How are thymic disorders diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves imaging studies (CT, MRI, PET scans), laboratory tests (autoantibody panels, hormone levels), and in some cases, biopsies or genetic tests, especially for congenital conditions like DiGeorge syndrome.

What treatments are available for thymic disorders?

Treatment varies by condition. Options include medications (corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, cholinesterase inhibitors), surgical interventions such as thymectomy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy for malignancies, and emerging therapies like targeted immunotherapy.

Disclaimer & Sharing

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for personalized diagnosis and treatment options.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social platform to help spread awareness and promote thymus health.