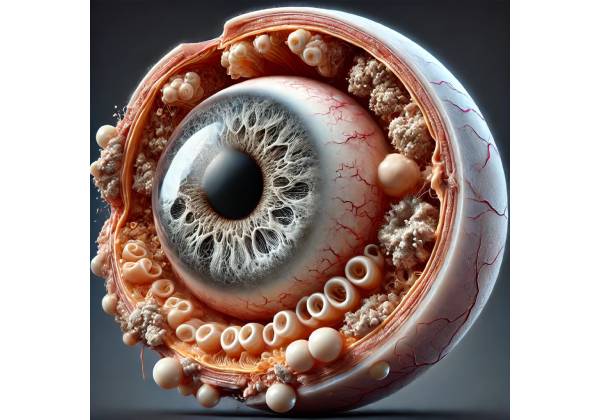

Uveal metastasis is the most common type of intraocular malignancy, which occurs when cancer cells from a primary tumor elsewhere in the body spread to the uveal tract in the eye. The three main components of the uveal tract are the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. The choroid is the most common site for metastatic deposits due to its abundant vascular supply, making it an ideal target for circulating cancer cells. Uveal metastasis is a serious condition that can cause significant visual impairment and signal advanced systemic disease.

Anatomy of the Uveal Tract

To understand uveal metastasis, one must first understand the anatomy of the uveal tract, which plays an important role in eye health and function.

- Iris: The iris is the colored part of the eye that regulates the amount of light that enters the eye by changing the size of the pupil.

- Ciliary Body: The ciliary body, located behind the iris, is responsible for the production of aqueous humor, the fluid that nourishes the eye and regulates intraocular pressure. It also houses the ciliary muscle, which adjusts the lens for focus.

- Choroid: The choroid is a vascular layer that exists between the retina and the sclera. It provides oxygen and nutrients to the retina’s outer layers and is essential for maintaining retinal health. The choroid’s extensive blood supply makes it especially vulnerable to metastatic deposits from other parts of the body.

Pathophysiology of Uveal Metastasis

Uveal metastasis occurs when malignant cells from a primary cancer in another part of the body travel through the bloodstream and settle in the uveal tract, most commonly the choroid. These cancer cells multiply, forming metastatic tumors that can disrupt the normal function of the eye and cause a variety of ocular symptoms.

- Primary Causes of Uveal Metastasis: The most common primary cancers that metastasize to the uveal tract are breast cancer and lung cancer. Together, these two cancers cause the vast majority of uveal metastases. Other cancers that can spread to the uvea include melanoma, gastrointestinal cancers, renal cell carcinoma, and thyroid cancer. Breast cancer is the most common cause of uveal metastasis in women, whereas lung cancer is more commonly the primary site in men.

- Metastasis Mechanism: Metastasis is a multi-step process. First, cancer cells must separate from the primary tumor and invade nearby blood vessels (a process known as intravasation). Once in the bloodstream, these cells must withstand the immune response and physical forces of circulation. Eventually, the cells leave the bloodstream (extravasation) and settle in a new location, where they multiply and form a metastatic tumor. The rich vascular network of the choroid creates an ideal environment for metastatic cancer cells to thrive.

- Growth and Impact on the Eye: Once established in the choroid or other parts of the uveal tract, metastatic tumors can progress and cause a variety of ocular symptoms. These tumors may cause retinal detachment, increased intraocular pressure, and optic nerve damage, all of which can result in visual impairment or loss. Furthermore, the presence of a metastatic tumor in the eye can cause inflammation and other complications that impair vision.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Uveal metastasis is uncommon compared to other types of metastatic cancer, but it is the most common intraocular malignancy. The exact incidence of uveal metastasis is difficult to determine because it frequently occurs in the context of widespread metastatic disease and may go undetected if the patient is asymptomatic.

- Age and Gender: Uveal metastasis can occur at any age, but it is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged and elderly people, mirroring the age distribution of the most common primary cancers (breast and lung cancer). There is a slight female predominance, most likely due to the higher prevalence of breast cancer.

- Primary Tumor Characteristics: The type, location, and stage of the primary tumour determine the likelihood of developing uveal metastasis. Tumors with a high metastasis potential, such as breast and lung cancer, are more likely to spread to the uveal tract. Furthermore, larger primary tumors and those with lymphatic or vascular invasion have a higher risk of metastasis.

- Systemic Metastatic Disease: Uveal metastasis is frequently associated with more widespread metastatic disease. Patients with metastatic breast or lung cancer, for example, may develop uveal metastases as part of a larger pattern of spread. In some cases, uveal metastasis may be the first sign of metastatic disease, emphasising the importance of a thorough examination when a metastatic lesion is discovered in the eye.

- Genetic Factors: Although the exact genetic factors linked to uveal metastasis are unknown, certain genetic mutations or chromosomal abnormalities in the primary tumor may increase the risk of metastasis. Mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which cause hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, may also increase the risk of uveal metastasis in affected individuals.

Clinical Features of Uveal Metastasis

The symptoms of uveal metastasis can differ greatly depending on the location and size of the metastatic tumor, as well as the presence of any secondary changes in the eye. In many cases, patients are asymptomatic, especially in the early stages of the disease, and the metastasis is discovered coincidentally during a routine eye examination or imaging study.

- Visual Disturbances: The most common sign of uveal metastasis is a change in vision. Patients may experience blurred vision, visual field defects, or the appearance of floaters (small dots or lines that move across the field of vision). These symptoms are frequently caused by the tumor’s effect on the retina or the presence of subretinal fluid as a result of retinal detachment.

- Photopsia: Photopsia, or seeing flashes of light, is another common symptom of uveal metastasis. This happens when the growing tumor mechanically stimulates the retina or when the retina detaches.

- Ocular Pain: Some patients with uveal metastasis may experience ocular pain, especially if the tumor causes inflammation, raises intraocular pressure (glaucoma), or invades the sclera. Pain may also occur if the metastasis progresses to secondary angle-closure glaucoma, in which the tumor obstructs the eye’s drainage angle, resulting in a rapid increase in intraocular pressure.

- Visible Mass: In some cases, especially when metastasis occurs in the iris or ciliary body, the tumor may appear as a dark spot or mass within the eye. The patient may notice this or an eye examination may reveal it. Iris metastases can change the shape or size of the pupil or cause secondary glaucoma if they obstruct the drainage of aqueous humor.

- Asymptomatic Cases: Many cases of uveal metastasis are asymptomatic, particularly in their early stages. These tumors are frequently discovered during routine eye exams, imaging studies conducted for other purposes, or as part of the evaluation of a known primary cancer. Asymptomatic metastases can still pose a significant risk to vision and necessitate close monitoring and management.

Types of Uveal Metastasis

Uveal metastasis can affect any part of the uveal tract, and the clinical symptoms may differ depending on the location of the metastatic deposit.

- Choroidal Metastasis is the most common type of uveal metastasis, accounting for approximately 88% of cases. These tumors usually appear as yellowish, flat, or slightly elevated lesions in the posterior pole of the eye. Choroidal metastases are commonly multifocal and bilateral, especially in patients with breast or lung cancer.

- Iris Metastasis: Iris metastases are uncommon, but they can cause severe symptoms due to their location in the anterior segment of the eye. These tumors can appear as a visible mass in the iris, causing changes in pupil shape or size, or leading to secondary glaucoma. Iris metastases are more likely to occur unilaterally and are frequently associated with lung cancer.

- Ciliary Body Metastasis: Ciliary body metastases are the least common type of uveal metastasis, but they can be difficult to detect because they are behind the iris. These tumors may cause secondary glaucoma or lens displacement, resulting in visual disturbances. Ciliary body metastases may also be associated with anterior uveitis, which is inflammation of the eye’s anterior segment.

Complications Of Uveal Metastasis

- Metastatic Spread: The presence of uveal metastasis is frequently associated with systemic metastatic disease, which has a significant impact on the patient’s overall prognosis. The presence of uveal metastasis may indicate that the cancer has spread to other organs, including the liver, lungs, brain, and bones. This widespread metastatic involvement can complicate treatment and is usually associated with a poor prognosis. The presence of uveal metastasis may necessitate more aggressive systemic therapy to control the primary cancer and prevent additional metastatic spread.

- Inflammation and Uveitis: Uveal metastasis can cause inflammation inside the eye, known as uveitis. This inflammation can cause pain, redness, light sensitivity, and even lead to vision loss. In some cases, the inflammatory response to the tumor can result in the formation of posterior synechiae (adhesions between the iris and lens), complicating treatment and deteriorating visual outcomes.

- Retinal Detachment: The progression of metastatic tumors in the choroid can result in a serous retinal detachment, in which fluid accumulates between the retina and the underlying choroid. This detachment can result in sudden vision loss, visual field defects, and photopsia. Retinal detachment is a severe complication that may necessitate immediate surgical intervention to avoid permanent vision loss.

Diagnostic Approaches for Uveal Metastasis

Uveal metastasis is diagnosed using a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging techniques, and, in some cases, histopathological confirmation. An accurate diagnosis is essential for guiding treatment and determining the severity of systemic disease.

Clinical Evaluation

- Comprehensive Eye Examination: The first step in diagnosing uveal metastasis is a comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist. This examination evaluates visual acuity, pupillary reactions, and intraocular pressure. The clinician will use a slit-lamp biomicroscope to inspect the anterior segment of the eye, including the iris and ciliary body, for any visible masses or changes in the eye’s normal anatomy. A dilated fundus examination is essential for assessing the retina and choroid. The ophthalmologist will look for signs of metastatic lesions, such as yellowish, flat, or slightly elevated masses in the choroid, which are frequently associated with subretinal fluid and retinal detachment.

- Indirect Ophthalmoscopy: Indirect ophthalmoscopy provides a larger field of view of the retina and allows for examination of the peripheral retina, which may also contain metastatic lesions. This technique is especially useful for detecting multifocal or bilateral metastases, which are common in uveal metastases caused by breast or lung cancer.

Imaging Studies

- Ultrasonography (B-Scan Ultrasound): B-scan ultrasonography is an effective diagnostic tool for determining the size, shape, and internal characteristics of uveal metastases. This non-invasive imaging technique uses sound waves to generate cross-sectional images of the eye, allowing the clinician to assess the tumor’s echogenicity. On B-scan ultrasound, uveal metastases are typically low-to-medium reflectivity lesions. Subretinal fluid, retinal detachment, and choroidal thickening can also be seen, which aids in the diagnosis.

- Fluorescein Angiography (FA) is an imaging technique that uses an intravenous injection of fluorescein dye to highlight the blood vessels in the retina and choroid. FA can reveal fluorescence patterns associated with uveal metastasis, such as hyperfluorescence caused by abnormal blood vessel leakage and tumor-induced fluorescence blockage. This method is especially useful for determining the vascularity of the tumor and detecting associated retinal abnormalities like choroidal neovascularization or exudative retinal detachment.

- Indocyanine Green Angiography (ICGA): ICGA is similar to FA but uses indocyanine green dye to provide a better view of the choroidal vasculature. ICGA is particularly effective at detecting deeply pigmented lesions or tumors in the posterior choroid. It can aid in distinguishing uveal metastasis from other choroidal diseases, such as choroidal melanoma and central serous chorioretinopathy.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique that produces high-resolution cross-sections of the retina and choroid. In cases of uveal metastasis, OCT can detect retinal abnormalities such as subretinal fluid, retinal edema, or detachments. Enhanced depth imaging OCT (EDI-OCT) improves choroid visualization and can reveal more about the metastatic lesion’s thickness and extent.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is used to obtain detailed images of the eye, orbit, and surrounding structures, particularly when extraocular extension is suspected or a diagnosis is uncertain. MRI is especially useful for imaging soft tissues and distinguishing uveal metastasis from other intraocular tumors. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI can reveal additional information about the tumor’s vascularity and spread.

Histopathologic Confirmation

- Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy (FNAB): A biopsy may be required to confirm the diagnosis of uveal metastasis, particularly if imaging findings are inconclusive or there is a suspicion of a primary intraocular tumour. FNAB involves extracting a small sample of cells from the tumor with a fine needle for cytological analysis. Histopathological analysis can provide definitive confirmation of the tumor’s metastatic nature as well as aid in the identification of the primary source, particularly if the primary cancer is unknown.

- Cytology and Immunohistochemistry: A cytological examination of the biopsy sample can reveal the tumor’s cellular characteristics, whereas immunohistochemistry can detect specific markers that may indicate the origin of the metastasis. For example, breast cancer metastases may express estrogen or progesterone receptors, whereas lung cancer metastases may express TTF-1 or cytokeratin.

Systematic Evaluation

Given that uveal metastasis is frequently part of a larger pattern of metastatic disease, a comprehensive systemic evaluation is required. Imaging studies such as CT scans, PET scans, and bone scans may be used to determine metastatic spread to other organs. Blood tests to evaluate tumor markers, liver function, and other relevant parameters may also be used to determine the severity of the disease and guide treatment decisions.

Best Practices in Uveal Metastasis Management

Uveal metastasis is difficult to treat and usually necessitates a multidisciplinary approach because it is often a sign of advanced systemic disease. The primary goals of treatment are to preserve vision, control the local ocular tumour, and treat the underlying systemic malignancy. The size and location of the metastasis, the type of primary cancer, the patient’s overall health, and the presence of metastases in other parts of the body must all be considered when developing treatment strategies.

Localized Ocular Treatments

- Radiation therapy is one of the most commonly used treatments for uveal metastasis. The goal is to shrink the metastatic tumor while alleviating symptoms like pain and vision loss. In the management of uveal metastasis, there are several types of radiation therapy:

- External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT): EBRT uses high-energy radiation beams to target the tumor from outside the body. This method is effective at shrinking tumors and alleviating symptoms. However, it may result in side effects such as radiation retinopathy, optic neuropathy, and cataract formation.

- Plaque Radiotherapy (Brachytherapy): This involves applying a small, radioactive plaque to the sclera near the tumor. The plaque directs a high dose of radiation directly to the metastatic lesion while minimizing exposure to surrounding tissues. Brachytherapy is especially useful for treating smaller tumors and can help preserve vision.

- Laser Therapy: Laser treatments are sometimes used to treat small uveal metastases, especially those in the choroid.

- Transpupillary Thermotherapy (TTT): An infrared laser delivers heat directly to the tumor, causing the tumor cells to coagulate and die. This treatment is less invasive and can be done in an outpatient setting. However, TTT is typically reserved for small, thin tumors and may be ineffective for larger or thicker lesions.

- Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Injections: Anti-VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) injections are used to inhibit the formation of new blood vessels, which promote tumor growth and contribute to complications such as macular edema and retinal detachment. Drugs such as bevacizumab (Avastin) and ranibizumab (Lucentis) are injected directly into the eye’s vitreous cavity to target these new vessels. While this treatment can help control tumor-related complications, it is usually used in combination with other therapies rather than as the sole treatment.

- Enucleation: Enucleation, or surgical removal of the eye, is considered when the tumor is large and causes severe pain, or when other treatments have failed to control the tumor. While enucleation effectively removes the metastatic tumor, it causes loss of vision in the affected eye. This procedure may be necessary if the tumor is causing severe pain or has caused significant structural damage to the eye. Enucleation is typically a last resort, reserved for patients with a very poor visual prognosis or severe symptoms.

Systemic Therapy

Because uveal metastasis is frequently part of a larger metastatic process, treating the primary cancer and managing systemic disease are critical. Systemic therapies can include:

- Chemotherapy: Systemic chemotherapy treats the primary cancer as well as any other metastatic sites in the body. The type of primary tumour determines the chemotherapeutic agents used. For example, breast cancer metastases may be treated with anthracyclines, taxanes, or platinum-based drugs, whereas lung cancer metastases may be treated with agents such as pemetrexed or cisplatin. Chemotherapy can help shrink metastatic lesions in the eye, but it is usually part of a more comprehensive treatment plan for the entire body.

- Hormonal Therapy: In cases of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, hormonal therapies such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors may be used to control the primary tumor and lower the risk of metastases. Hormonal therapy effectively slows the progression of hormone-dependent tumors, including those that have metastasized to the uveal tract.

- Targeted Therapy: Targeted therapies aim to disrupt specific molecular pathways involved in cancer growth and metastasis. Trastuzumab (Herceptin) can be used to treat HER2-positive breast cancer, whereas ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib may be effective for cancers with ALK gene mutations. Targeted therapy has the potential to improve systemic disease control and reduce the size of uveal metastases.

- Immunotherapy: Immunotherapy employs the body’s immune system to combat cancer. Certain cancers, including melanoma and lung cancer, that have metastasized to the uveal tract are treated with checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab (Keytruda) or nivolumab (Opdivo). Immunotherapy is a new treatment option that may be available as part of a clinical trial for patients with uveal metastasis.

Palliative Care and Symptom Management

Palliative care may become the primary focus of treatment for patients with advanced cancer and a limited life expectancy. The goal is to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life, and offer psychological support. Palliative treatments for uveal metastasis may include pain relief, anti-inflammatory medications, and counseling services to assist patients and their families in dealing with the emotional aspects of the disease.

Follow-Up and Monitoring

Patients with uveal metastasis require regular follow-up to monitor treatment response, detect disease recurrence or progression, and manage side effects. Follow-up usually includes:

- Ophthalmologic Examinations: Frequent eye exams are required to assess the condition of the treated eye, monitor for complications, and determine the effectiveness of therapy.

- Imaging Studies: Regular imaging of the eye and other affected organs, such as the liver or lungs, is essential for monitoring the progression of metastatic disease.

- Systemic Evaluation: Ongoing monitoring of the primary cancer and any other metastatic sites is required in order to adjust treatment as needed and manage systemic symptoms.

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with uveal metastasis varies according to the primary cancer type, the extent of metastatic disease, and treatment response. While local ocular treatments can help preserve vision and relieve symptoms, the primary cancer and the presence of metastases elsewhere in the body frequently determine the overall prognosis. Early detection, appropriate systemic therapy, and a multidisciplinary approach are critical for improving outcomes for patients with uveal metastasis.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Ocular Oncology: Principles and Practice” by Paul T. Finger and Dinesh Selva: This comprehensive resource covers the diagnosis and management of various ocular tumors, including uveal metastasis. It is an invaluable reference for ophthalmologists and oncologists.

- “Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology: Ocular and Adnexal Tumors” by Arun D. Singh and Bertil Damato: This book provides detailed information on the clinical aspects of ocular oncology, with a focus on the management of metastatic tumors affecting the eye.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO): The AAO offers extensive resources on eye health, including information on the management of ocular metastases. Their website provides access to clinical guidelines, research articles, and educational materials for both patients and healthcare professionals.

- Ocular Melanoma Foundation (OMF): While primarily focused on primary ocular melanoma, the OMF provides valuable resources and support for patients with metastatic eye disease. The foundation offers educational materials, patient support networks, and information on clinical trials and emerging therapies.