Introduction

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma (CACG) is a progressive eye condition marked by the gradual closure of the anterior chamber angle, resulting in an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP). If not treated properly, this elevated pressure can damage the optic nerve, potentially leading to vision loss or blindness. Chronic angle-closure glaucoma develops slowly over time, with few symptoms in the early stages. This makes it a particularly insidious type of glaucoma, as the absence of early warning signs can delay diagnosis and treatment. Understanding CACG is critical for early detection and effective management, resulting in improved visual outcomes for patients.

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma Insights

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma (CACG) is a complicated and multifaceted eye disease. It is one of the most common forms of glaucoma, a group of eye conditions that cause damage to the optic nerve, which is required for clear vision. This damage is frequently caused by elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) and can result in permanent vision loss.

Pathophysiology of CACG

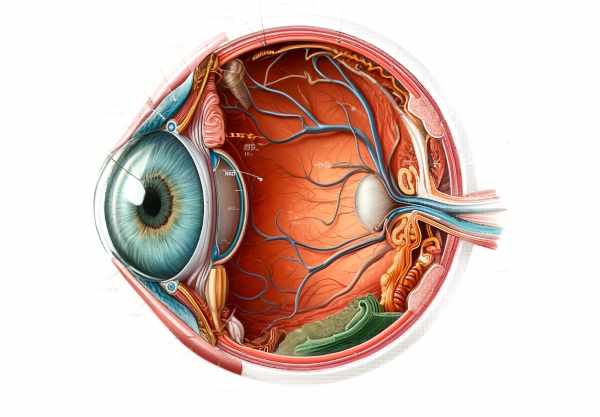

CACG pathophysiology is concerned with the anatomical and functional characteristics of the anterior chamber of the eye. The anterior chamber is the fluid-filled space that separates the cornea and the iris. This fluid, known as aqueous humor, drains through a network of tissues called the trabecular meshwork, which is located at the angle where the iris and cornea meet. In CACG, this angle gradually narrows over time, leading to partial or complete closure.

A shallow anterior chamber, a thick or anteriorly positioned lens, or a small corneal diameter can all cause the anterior chamber angle to close. These characteristics are more frequently observed in hyperopic (farsighted) eyes. As the angle narrows, the trabecular meshwork becomes less accessible, limiting aqueous humor outflow and resulting in elevated IOP.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

CACG is more prevalent in some populations. It is more common in people of Asian descent, particularly those from East Asia, than in Caucasians or African Americans. This increased prevalence is due to anatomical differences, such as shallower anterior chambers, which predispose these groups to angle closure.

Age is another major risk factor. The risk of developing CACG rises with age as the lens size and position change, contributing to a narrowing of the anterior chamber angle. Women are also at a higher risk than men, most likely due to anatomical differences like shorter axial lengths and shallower anterior chambers.

Symptoms and Progressions

One of the most difficult aspects of CACG is its asymptomatic nature in the early stages. Patients frequently do not exhibit obvious symptoms until significant optic nerve damage has occurred. When symptoms appear, they may include blurred vision, halos around lights, eye pain, headaches, and, in severe cases, nausea and vomiting.

The progression of CACG can be subtle. Initially, angle closure may be intermittent, with periods of normal IOP followed by spikes. Over time, these episodes can become more frequent and prolonged, eventually leading to permanent angle closure and persistently elevated IOP. If left untreated, this persistently high pressure can cause progressive optic nerve damage and peripheral vision loss, which can progress to central vision impairment.

Mechanisms for Angle Closure

Several mechanisms may contribute to the angle closure observed in CACG. These mechanisms can be broadly classified into primary and secondary causes.

Primary mechanisms:

- Pupillary Block: The most common mechanism, in which the flow of aqueous humor from the posterior to the anterior chamber is obstructed by the pupil. This creates a pressure gradient, pushing the iris forward and narrowing the angle.

- Plateau Iris Configuration: This happens when the ciliary body pushes the peripheral iris forward, resulting in angle closure despite normal anterior chamber depth.

Secondary mechanisms:

- Lens-Induced Mechanisms: As the lens enlarges with age, the iris moves forward, contributing to angle closure.

- Other Pathologies: Uveitis, neovascularization, and tumors can all cause secondary angle closure.

Clinical Evaluation

A thorough clinical evaluation is required for diagnosing and managing CACG. Key elements of the evaluation include:

- Gonioscopy: A critical examination technique that uses a special lens to view the anterior chamber angle directly. It aids in determining the degree of angle closure and detecting synechiae (adhesions) between the iris and trabecular meshwork.

- Slit-Lamp Examination: This examination evaluates the anterior segment structures, including the depth of the anterior chamber and the presence of any additional causes of angle closure.

- Optic Nerve Assessment: A thorough examination of the optic nerve head using ophthalmoscopy or optical coherence tomography (OCT) to detect glaucomatous damage.

- Visual Field Testing: Perimetry is used to detect functional vision loss, specifically peripheral vision, which is frequently affected first in glaucoma.

Genetic Factors and Research

Emerging research has highlighted the importance of genetic factors in CACG. Several genetic loci have been linked to an increased risk of developing the condition. These findings point to a hereditary component, in which specific genetic variants can predispose people to anatomical features that increase the likelihood of angle closure.

The molecular pathways involved in CACG are currently being investigated. Identifying these pathways could lead to new therapeutic targets and more effective screening methods for at-risk populations. Advances in genetic testing may eventually enable personalized approaches to prevention and treatment, improving outcomes for patients with a familial predisposition to CACG.

Effects on Quality of Life

CACG has the potential to significantly improve patients’ quality of life. Loss of vision over time can have an impact on daily activities, mobility, and independence. Patients may have difficulty with tasks like reading, driving, and recognizing faces. This loss of function can cause emotional distress, anxiety, and depression.

Furthermore, the disease’s chronic nature necessitates continuous monitoring and treatment, which can be a significant burden for patients. CACG’s long-term management challenges include regular visits to the ophthalmologist, adherence to medication regimens, and the possibility of surgical intervention.

Prevention Tips

Several strategies are used to prevent chronic angle-closure glaucoma, with the goal of reducing risk factors and promoting early detection. Here are some key preventive measures:

- Regular Eye Examination:

- Get routine comprehensive eye exams, especially if you’re over 40 or have a family history of glaucoma or hyperopia.

- Awareness of symptoms:

- Be aware of symptoms such as blurred vision, halos around lights, eye pain, and headaches, and seek medical attention immediately if they occur.

- Family history:

- Inform your eye care provider if you have a family history of glaucoma, as this can help assess your risk and determine the frequency of your eye exams.

- Protective eyewear:

- Wear protective eyewear when participating in activities that may cause eye injury, as trauma can increase the risk of secondary angle-closure glaucoma.

- A Healthy Lifestyle:

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle that includes regular exercise, a balanced diet, and quitting smoking, as these can all improve overall eye health.

- Control Systemic Conditions:

- Manage systemic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, which can lead to the development of eye diseases like glaucoma.

- Medical Awareness:

- Exercise caution with medications that can affect pupil size and potentially cause angle closure, and discuss any concerns with your healthcare provider.

- Laser Iridotomy:*

- In high-risk patients, prophylactic laser iridotomy may be used to prevent angle closure by creating a small hole in the peripheral iris to improve aqueous humor flow.

Diagnostic methods

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma (CACG) is diagnosed using a combination of standard clinical techniques and advanced imaging technologies. Early and accurate diagnosis is critical for the effective treatment and prevention of irreversible vision loss.

Gonioscopy

Gonioscopy is the gold standard for determining the anterior chamber angle. During this examination, an ophthalmologist places a special contact lens with mirrors on the eye, allowing them to see the angle directly. This technique aids in determining the degree of angle closure and identifying synechiae (adhesions) between the iris and the trabecular meshwork. Gonioscopy is required to distinguish between reversible (appositional) and irreversible (synechial) closure.

Anterior Segment Optical Coherence Tomography (AS-OCT)

AS-OCT is a non-invasive imaging technique for obtaining high-resolution cross-sectional images of the anterior segment of the eye. It provides a detailed view of the anterior chamber angle, including the iris, trabecular meshwork, and ciliary body. AS-OCT can quantify angle parameters like angle width and anterior chamber depth, which helps to assess angle closure and monitor disease progression.

Ultrasound Biomicroscopy (UBM)

UBM generates detailed images of the anterior segment structures using high-frequency ultrasound technology. It is especially useful in determining the position and configuration of the ciliary body and lens. UBM can help identify underlying anatomical abnormalities that cause angle closure, such as plateau iris configuration or lens-related mechanisms.

Intraocular Pressure Measurement

Measuring intraocular pressure (IOP) is an important part of glaucoma diagnosis. Elevated IOP is a significant risk factor for optic nerve damage in CACG. IOP is accurately measured using a variety of tonometers, including Goldmann applanation tonometry. Regular IOP monitoring is critical for determining the effectiveness of treatment and preventing further optic nerve damage.

Optical Nerve Imaging

Evaluating the optic nerve for glaucomatous damage is critical in CACG diagnosis. Fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) are methods for obtaining detailed images of the optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer. These imaging techniques aid in detecting structural changes associated with glaucoma, such as nerve fiber layer thinning and optic disc cupping.

Visual Field Testing

Perimetry, or visual field testing, evaluates the functional impact of glaucomatous damage on vision. Automated perimetry, such as the Humphrey Field Analyzer, maps the visual field and detects areas of vision loss. This test is critical for identifying early functional deficits and tracking disease progression.

Combining these diagnostic methods allows ophthalmologists to accurately diagnose CACG, assess its severity, and tailor treatment strategies to prevent vision loss.

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma Treatment Options

Chronic Angle-Closure Glaucoma (CACG) is treated with a combination of medications, lasers, and surgeries. The primary goals are to reduce intraocular pressure (IOP), prevent further optic nerve damage, and maintain vision.

Medical Treatment

Medical treatment is frequently the first line of therapy for CACG. Several types of medications are used to reduce IOP, including:

- Prostaglandin Analogues: These drugs increase the outflow of aqueous humor via the uveoscleral pathway, effectively lowering IOP levels. Examples include bimatoprost and latanoprost.

- Beta-blockers: These medications reduce aqueous humor production, which helps to lower IOP. Timolol and betaxolol are two commonly used beta blockers.

- Alpha Agonists: These drugs reduce aqueous humor production while increasing uveoscleral outflow. Brimonidine is a commonly used alpha agonist.

- Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: These medications lower aqueous humor production. They are available in two forms: topical (dorzolamide) and oral (acetazolamide).

- Rho Kinase Inhibitors: A novel class of drugs that reduce IOP by increasing trabecular meshwork outflow. Netarsudil is an example of this category.

Laser Therapy

Laser therapy is an important intervention for patients with CACG, especially those with narrow angles that are at risk of closing.

- Laser Peripheral Iridotomy (LPI): This procedure uses a laser to create a small hole in the peripheral iris. This procedure increases the flow of aqueous humor from the posterior to the anterior chamber, relieving pupillary block and opening the angle.

- Laser Iridoplasty: This procedure uses laser energy to contract the peripheral iris, separating it from the trabecular meshwork and widening the angle. It is especially useful for plateau iris configurations.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is considered when medical and laser therapies fail to control IOP or there is significant angle closure.

- Trabeculectomy: This surgical procedure creates a new drainage pathway for aqueous humor to exit the eye, resulting in lowered IOP. It entails making a small flap in the sclera and a drainage reservoir (bleb) beneath the conjunctiva.

- Glaucoma Drainage Devices: Also known as shunts or tubes, these devices are implanted to provide an alternative drainage route for aqueous humor that avoids the obstructed trabecular meshwork.

- Lens Extraction: If a thick or anteriorly positioned lens causes angle closure, cataract surgery or clear lens extraction can help widen the angle and lower IOP.

Emerging Therapies

Innovative therapies for CACG are constantly being developed. Some of the promising emerging treatments are:

- Minimally Invasive Glaucoma Surgery (MIGS): MIGS procedures, such as the implantation of micro-stents and trabecular bypass devices, are less invasive than traditional surgery, with shorter recovery times and fewer complications.

- Gene Therapy: Research is ongoing into gene therapy approaches that target the underlying molecular mechanisms of glaucoma, with the goal of providing long-term solutions for IOP control and optic nerve protection.

Ophthalmologists can effectively manage CACG and prevent further vision loss by combining these treatment modalities and tailoring them to each individual patient’s condition and response to therapy.

Trusted Resources

Books

- Shields’ Textbook of Glaucoma by R. Rand Allingham, Karim F. Damji, Sharon Freedman, Sayoko E. Moroi, and Douglas Rhee

- Glaucoma: Medical Diagnosis & Therapy by Tarek Shaarawy, Mark B. Sherwood, Roger A. Hitchings, and Jonathan G. Crowston

- The Glaucoma Book: A Practical, Evidence-Based Approach to Patient Care by Paul N. Schacknow and John R. Samples