The esophagus is a muscular tube that plays a vital role in digestion by transporting food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach. Acting as a critical link in the digestive system, it not only ensures the efficient passage of ingested materials but also helps prevent reflux of stomach acid into the upper digestive tract. Its intricate structure—divided into the cervical, thoracic, and abdominal segments—comprises multiple layers and specialized sphincters that work in concert to facilitate swallowing and protect against injury. This guide provides an in-depth exploration of esophageal anatomy, physiology, disorders, diagnostic techniques, and treatment strategies, along with nutritional and lifestyle tips to maintain optimal esophageal health.

Table of Contents

- Structural Overview & Composition

- Physiological Mechanisms & Digestive Functions

- Common Esophageal Disorders & Clinical Manifestations

- Diagnostic Techniques & Evaluation Methods

- Treatment Strategies & Therapeutic Interventions

- Nutritional Strategies & Supplementation

- Lifestyle Practices for Esophageal Wellness

- Trusted Resources & Further Reading

- Frequently Asked Questions

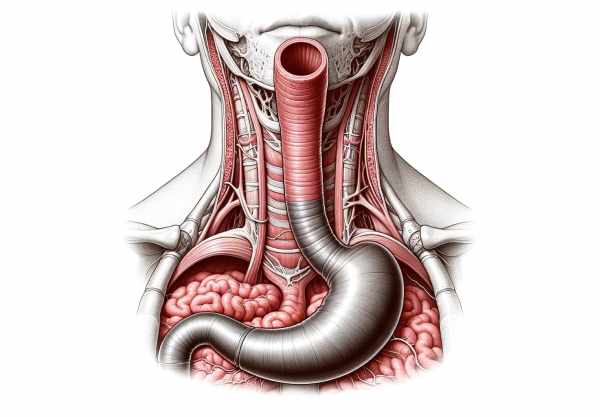

Structural Overview & Composition

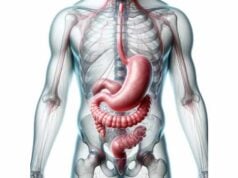

The esophagus is a dynamic, muscular conduit essential for delivering ingested food and liquids to the stomach. Its structure is remarkably complex, comprising three distinct regions and multiple layers, each designed to withstand the rigors of continuous mechanical and chemical stress while ensuring smooth transit.

Regional Anatomy

- Cervical Esophagus:

Beginning at the lower border of the cricoid cartilage, the cervical esophagus is composed predominantly of skeletal muscle. This segment provides voluntary control during the initiation of swallowing, ensuring that the food bolus is safely directed from the pharynx into the esophageal tube. - Thoracic Esophagus:

The longest segment, the thoracic esophagus, traverses the mediastinum between the trachea and the vertebral column. As it descends, it gradually transitions from skeletal to smooth muscle, which takes over the process of peristalsis. Its position in the thorax makes it a key component in the coordination of swallowing and in protecting adjacent structures. - Abdominal Esophagus:

The shortest segment, the abdominal esophagus, passes through the diaphragm to join the stomach. It is encircled by the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a functional muscle group that plays a crucial role in preventing the reflux of acidic gastric contents back into the esophagus.

Layered Structure

The esophageal wall is composed of several layers, each with a distinct role:

- Mucosa:

The innermost lining is a stratified squamous epithelium that provides robust protection against abrasion and injury from the passage of food. This layer also houses mucous glands that secrete a lubricating mucus, easing the movement of the bolus. - Submucosa:

Beneath the mucosa lies the submucosa, a supportive layer containing connective tissue, blood vessels, and additional mucous glands. This layer reinforces the mucosal barrier and facilitates nutrient and oxygen delivery to the esophageal wall. - Muscularis Externa:

The muscular layer is divided into an inner circular and an outer longitudinal muscle. This dual-layer arrangement is responsible for peristalsis, the coordinated contractions that propel food downward. Notably, the upper third is primarily skeletal muscle, allowing voluntary control, whereas the lower two-thirds consist mostly of smooth muscle, ensuring sustained involuntary contractions. - Adventitia:

The outermost layer is composed of connective tissue that anchors the esophagus to surrounding structures in the neck, chest, and abdomen. It provides the necessary support and stability for the esophagus during the constant process of swallowing.

Sphincters and Openings

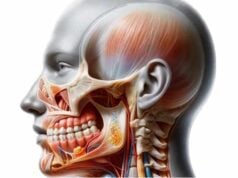

Two critical sphincters regulate the passage of material into and out of the esophagus:

- Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES):

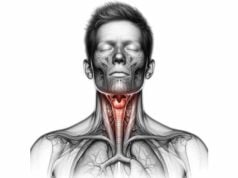

Located at the junction of the pharynx and esophagus, the UES is comprised of skeletal muscle. It opens during swallowing to allow food entry and closes promptly to prevent air from entering the esophagus during breathing. - Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES):

Situated at the distal end, where the esophagus meets the stomach, the LES is a tonically contracting smooth muscle that relaxes only during swallowing. Its primary function is to prevent the backflow of acidic gastric contents, thereby protecting the esophageal lining from acid damage.

Vascular Supply and Innervation

- Arterial Supply:

The esophagus is nourished by multiple arteries. The cervical portion is supplied by the inferior thyroid artery, while branches from the thoracic aorta serve the thoracic esophagus. The abdominal segment receives blood from the left gastric and inferior phrenic arteries. - Venous Drainage:

Venous return is achieved through the azygos system in the thorax and the left gastric vein in the abdomen. This arrangement is particularly significant in conditions such as portal hypertension, where abnormal blood flow can lead to esophageal varices. - Innervation:

The esophagus receives both parasympathetic input from the vagus nerve and sympathetic input from the thoracic sympathetic chain. The vagus nerve, in particular, is essential for coordinating peristalsis and regulating the function of the sphincters.

In summary, the esophagus is a marvel of anatomical engineering. Its distinct regions, layered structure, and specialized sphincters work together to ensure the safe and efficient passage of food and liquids, while its robust blood supply and innervation provide the support necessary for its continuous, high-demand function.

Physiological Mechanisms & Digestive Functions

The esophagus is integral to the digestive system, performing the essential task of transporting ingested materials from the mouth to the stomach. Its complex physiology involves a coordinated interplay of voluntary and involuntary actions that ensure effective swallowing and protect the organ from damage.

Swallowing and Peristalsis

- Initiation of Swallowing:

The process begins with the voluntary oral phase, where food is chewed and mixed with saliva to form a cohesive bolus. The tongue then propels the bolus toward the pharynx, triggering the involuntary pharyngeal phase. During this phase, the soft palate elevates to close off the nasal passages, and the epiglottis folds to protect the airway as the bolus enters the esophagus. - Peristaltic Contractions:

Once the bolus enters the esophagus, a series of coordinated muscular contractions, known as peristalsis, propels it toward the stomach. This process is driven by the muscularis externa, with the sequential contraction of the circular muscles followed by the relaxation of the longitudinal muscles. This wave-like movement ensures that the bolus is efficiently transported without backflow.

Sphincter Function and Pressure Regulation

- Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES):

The UES relaxes at the onset of swallowing, allowing the bolus to pass from the pharynx into the esophagus. Once the bolus has entered, the UES contracts to prevent regurgitation and air entry, maintaining an optimal environment for peristalsis. - Lower Esophageal Sphincter (LES):

The LES maintains a baseline tone that prevents the reflux of acidic gastric contents. It relaxes transiently during swallowing to permit the entry of food into the stomach and then contracts immediately to restore the barrier. This crucial function protects the esophageal mucosa from corrosive stomach acids and enzymes.

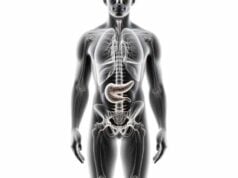

Coordination with the Stomach and Other Digestive Organs

- Integration with Gastric Function:

The esophagus and stomach work in tandem to ensure that food is properly processed. Once the bolus enters the stomach, the LES quickly closes to prevent reflux, thereby maintaining the stomach’s acidic environment necessary for digestion. This coordinated action is essential for efficient nutrient breakdown and absorption. - Sensory Feedback and Regulation:

Sensory receptors in the esophageal lining detect factors such as bolus size, texture, and temperature, sending feedback to the brain. This sensory input helps modulate the strength and timing of peristaltic waves, ensuring that the swallowing process is precisely controlled.

Protective Mechanisms

- Mucosal Barrier:

The stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus acts as a protective shield, safeguarding the underlying tissues from mechanical abrasion and chemical damage. The mucus secreted by glands in the mucosa further lubricates the passage of food and shields the esophagus from potential irritants. - Acid Defense:

The LES plays a critical role in preventing the backflow of acidic stomach contents. In addition, cellular mechanisms within the esophageal mucosa repair minor injuries, thereby maintaining a robust barrier against acid-related damage.

Additional Functions

- Facilitating Satiety:

Sensory signals from the esophagus contribute to the sensation of fullness and help regulate food intake. The timely passage of the bolus into the stomach, coupled with the activation of sensory receptors, can influence satiety signals and overall appetite control. - Coordination with the Nervous System:

The esophagus is under both voluntary and autonomic control, allowing for a finely tuned process that adapts to various physiological conditions. The central nervous system, through the vagus nerve and other pathways, integrates these signals to coordinate the entire swallowing process, ensuring that it is both effective and efficient.

In essence, the esophagus is a critical conduit in the digestive system, employing a sophisticated array of physiological mechanisms to ensure that food and liquids are safely transported to the stomach. Its ability to regulate pressure, coordinate with adjacent organs, and protect its delicate tissues highlights its importance in maintaining digestive health and overall well-being.

Common Esophageal Disorders & Clinical Manifestations

The esophagus is susceptible to various disorders that can impair its function, cause discomfort, and lead to significant health complications. Early recognition of these conditions is essential for timely treatment and prevention of long-term damage.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- Pathophysiology:

GERD is a chronic condition characterized by the reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus due to a weakened or dysfunctional lower esophageal sphincter (LES). This acid exposure can cause inflammation, erosions, and even ulceration of the esophageal lining. - Symptoms:

Typical symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, and difficulty swallowing. Chronic GERD may lead to complications such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus (a precancerous condition), and esophageal strictures. - Management:

Diagnosis is often confirmed via endoscopy, pH monitoring, and manometry. Treatment involves lifestyle modifications (such as weight loss and dietary changes), medications like proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 receptor antagonists, and in severe cases, surgical interventions such as fundoplication.

Esophageal Cancer

- Types and Risk Factors:

Esophageal cancer primarily presents in two forms: squamous cell carcinoma, often linked to smoking and alcohol use, and adenocarcinoma, which is commonly associated with chronic GERD and Barrett’s esophagus. Risk factors include age, gender, dietary habits, and exposure to carcinogens. - Clinical Presentation:

Symptoms include progressive difficulty swallowing, unintended weight loss, chest pain, and chronic cough. Early-stage esophageal cancer is often asymptomatic, underscoring the importance of screening in high-risk populations. - Diagnosis and Treatment:

Diagnostic tools include endoscopy with biopsy, imaging studies (CT, MRI, PET scans), and staging evaluations. Treatment options vary depending on the stage and include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted therapies.

Achalasia

- Mechanism and Causes:

Achalasia is a rare motility disorder where the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to relax properly, and esophageal peristalsis is diminished. The etiology may involve autoimmune or neurodegenerative processes affecting the esophageal nerves. - Symptoms:

Patients typically experience progressive dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain, and weight loss. The condition can lead to significant nutritional deficiencies if left untreated. - Diagnosis and Management:

Diagnosis is confirmed through esophageal manometry, barium swallow studies, and endoscopy. Treatment options include pneumatic dilation, Heller myotomy, and the newer peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), which effectively reduce LES pressure.

Esophageal Strictures

- Pathogenesis:

Strictures are narrowings of the esophageal lumen, usually resulting from chronic acid reflux, radiation therapy, or ingestion of caustic substances. Scar tissue formation leads to progressive narrowing, impeding the passage of food. - Clinical Features:

Symptoms include progressive dysphagia, food impaction, and chest discomfort. Chronic strictures may lead to significant nutritional deficiencies and weight loss. - Treatment:

Endoscopic dilation is the primary treatment for esophageal strictures. In severe cases, additional interventions such as steroid injections or surgical resection may be necessary.

Barrett’s Esophagus

- Definition and Risk:

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition where the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by columnar epithelium due to chronic acid reflux. This metaplastic change increases the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. - Symptoms:

While Barrett’s esophagus is often asymptomatic, it is typically associated with chronic GERD symptoms. Regular monitoring is essential due to its potential for malignant transformation. - Management:

Treatment focuses on controlling GERD symptoms with medications and lifestyle modifications. Surveillance endoscopies and, in some cases, endoscopic ablative therapies are employed to manage dysplastic changes.

Other Esophageal Conditions

- Esophageal Varices:

Often associated with portal hypertension in liver cirrhosis, varices are dilated submucosal veins that pose a risk of life-threatening bleeding. - Esophagitis:

Inflammation of the esophageal lining can result from infections, medications, or chemical irritants. Symptoms include pain, difficulty swallowing, and chest discomfort, which are managed with medications and supportive care.

These conditions illustrate the wide spectrum of disorders that can affect the esophagus. Their impact on both quality of life and overall health underscores the importance of early diagnosis and comprehensive treatment strategies.

Diagnostic Techniques & Evaluation Methods

Accurate diagnosis of esophageal disorders is essential for guiding effective treatment. A combination of clinical evaluation, imaging, and specialized tests is used to assess the structure and function of the esophagus, enabling healthcare providers to pinpoint the underlying causes of symptoms.

Endoscopic Evaluation

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD):

Endoscopy is the gold standard for visualizing the esophageal lining. During an EGD, a flexible endoscope is inserted through the mouth to inspect the mucosa, identify inflammation, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, or tumors, and obtain tissue biopsies if needed. This direct visualization is invaluable for both diagnosis and treatment planning.

Radiographic and Imaging Studies

- Barium Swallow Study:

In a barium swallow, the patient ingests a barium solution that coats the esophagus, allowing it to be seen clearly on X-ray images. This study evaluates the contour and motility of the esophagus, revealing structural abnormalities such as strictures, achalasia, or diverticula. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT imaging provides detailed cross-sectional views of the esophagus and surrounding structures. It is particularly useful in staging esophageal cancer and detecting complications such as perforations or mediastinal involvement. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI offers superior soft tissue contrast without radiation exposure, making it ideal for evaluating esophageal lesions, muscular layers, and adjacent tissues. It is especially useful when further characterization of abnormal findings is necessary.

Functional Testing

- Esophageal Manometry:

This test measures the pressure within the esophagus during swallowing. A catheter is inserted through the nose into the esophagus, and pressure sensors record muscle contractions. Manometry is crucial for diagnosing motility disorders such as achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm. - 24-Hour pH Monitoring:

pH monitoring involves placing a probe in the esophagus to continuously record acid exposure over 24 hours. This test confirms the diagnosis of GERD by quantifying acid reflux episodes and evaluating the effectiveness of acid-suppressing medications. - Impedance-pH Monitoring:

This advanced technique assesses both acid and non-acid reflux by measuring changes in electrical impedance along with pH levels. It is particularly useful for patients with atypical reflux symptoms.

Additional Diagnostic Tools

- Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS):

EUS combines endoscopy with ultrasound to create detailed images of the esophageal wall and surrounding structures. It is particularly valuable for staging esophageal cancer by assessing tumor depth and regional lymph nodes. - Capsule Endoscopy:

In select cases, a capsule endoscopy may be used to capture images of the esophageal lining. Although more commonly used for small intestine evaluation, it can provide supplementary data when traditional methods are inconclusive.

By integrating these diagnostic techniques, clinicians can accurately assess esophageal function and structure, leading to precise diagnoses and targeted treatment plans for a variety of esophageal conditions.

Treatment Strategies & Therapeutic Interventions

Managing esophageal disorders requires a multifaceted approach that may involve lifestyle modifications, medications, endoscopic procedures, and surgical interventions. Tailoring treatment to the specific condition and its severity is crucial for restoring function, alleviating symptoms, and preventing long-term complications.

Medical Management

- Pharmacotherapy:

- Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs):

PPIs are the cornerstone of GERD treatment. By reducing gastric acid secretion, they allow the esophageal lining to heal and help prevent further damage. - H2 Receptor Antagonists:

Used for milder cases of acid reflux, these medications reduce acid production and provide symptomatic relief. - Prokinetic Agents:

Drugs such as metoclopramide improve esophageal motility, facilitating the passage of food and reducing reflux symptoms. - Anti-inflammatory Medications:

Corticosteroids may be used in acute inflammatory conditions to reduce swelling and discomfort. - Lifestyle Modifications:

Dietary adjustments—such as avoiding spicy and fatty foods, reducing caffeine intake, and eating smaller, more frequent meals—can alleviate reflux symptoms. Weight loss, quitting smoking, and avoiding alcohol further support esophageal health.

Endoscopic Therapies

- Endoscopic Dilation:

For esophageal strictures, endoscopic dilation involves gently stretching the narrowed segment with balloons or dilators, improving the passage of food and reducing dysphagia. - Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR):

EMR is employed to remove early-stage cancers or precancerous lesions from the esophageal lining, allowing for tissue regeneration with healthier cells. - Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA):

RFA uses controlled heat energy to ablate dysplastic tissue in Barrett’s esophagus, reducing the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma. - Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM):

An innovative minimally invasive procedure for achalasia, POEM involves cutting the inner circular muscle of the esophagus to relieve outflow obstruction and improve swallowing.

Surgical Interventions

- Fundoplication:

Fundoplication is performed for patients with severe GERD who do not respond to medical management. During this procedure, the upper part of the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus to strengthen the LES, reducing reflux. - Heller Myotomy:

Used to treat achalasia, Heller myotomy involves surgically cutting the muscle fibers of the LES to allow food to pass more easily into the stomach. This procedure is often combined with a partial fundoplication to prevent reflux. - Esophagectomy:

In cases of advanced esophageal cancer or severe Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia, esophagectomy—the surgical removal of part or all of the esophagus—may be necessary. Reconstruction of the digestive tract is then performed using part of the stomach or colon.

Innovative and Regenerative Approaches

- Gene Therapy:

Research is underway to explore gene therapy for hereditary esophageal conditions and for cancers of the esophagus. This cutting-edge approach aims to correct genetic defects at the molecular level. - Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine:

Emerging therapies using stem cells and tissue engineering hold promise for repairing damaged esophageal tissue and restoring function, particularly in patients with severe reflux-induced damage. - Minimally Invasive and Robotic-Assisted Surgery:

Advances in robotic-assisted and laparoscopic surgery have improved the precision of esophageal procedures, reducing recovery times and minimizing complications.

Through a combination of these medical, endoscopic, and surgical treatments, clinicians can effectively manage esophageal disorders. Tailored treatment strategies not only alleviate symptoms but also improve quality of life and prevent the progression of disease.

Nutritional Strategies & Supplementation

Proper nutrition is a cornerstone of esophageal health, helping to maintain tissue integrity, reduce inflammation, and support overall digestive function. A balanced diet, along with specific supplements, can improve the esophageal environment and promote healing.

Key Vitamins and Minerals

- Vitamin D:

Adequate vitamin D levels are essential for immune function and tissue repair. In the context of esophageal health, vitamin D may help mitigate inflammation associated with GERD and esophagitis. - Vitamin B12:

Vitamin B12 supports nerve health and may be especially important for individuals on long-term acid-suppressing medications, which can interfere with B12 absorption. - Vitamin C:

As a potent antioxidant, vitamin C aids in collagen synthesis and protects the esophageal lining from oxidative stress. It is abundant in citrus fruits, berries, and leafy greens. - Calcium and Magnesium:

These minerals support muscular function and are integral for maintaining the structural integrity of the esophageal wall. Dairy products, green vegetables, and nuts are good sources.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Anti-inflammatory Benefits:

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fish oil, flaxseed, and walnuts, have strong anti-inflammatory properties. They can help reduce esophageal inflammation and improve overall digestive health.

Herbal and Natural Supplements

- Slippery Elm:

Slippery elm forms a protective, soothing barrier along the esophageal lining, which can alleviate irritation from acid reflux and reduce inflammation. - Licorice Root (DGL):

Deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL) is known to soothe the mucosal lining of the esophagus and reduce symptoms of heartburn and acid reflux. - Turmeric (Curcumin):

The active compound in turmeric, curcumin, has significant anti-inflammatory effects and may help protect the esophageal tissue from acid-induced damage.

Antioxidants

- N-Acetylcysteine (NAC):

NAC supports the production of glutathione, a critical antioxidant that defends esophageal cells against oxidative stress. - Alpha-Lipoic Acid:

This antioxidant helps reduce oxidative damage and inflammation in the esophageal tissues, contributing to overall tissue health.

By integrating these nutritional strategies and supplements into your daily regimen, you can support the repair and maintenance of the esophageal lining, reduce inflammation, and promote optimal digestive health.

Lifestyle Practices for Esophageal Wellness

Beyond medical treatments and nutrition, lifestyle choices play a significant role in maintaining esophageal health. Adopting proactive habits can help reduce symptoms of acid reflux, prevent tissue damage, and improve overall digestive function.

Dietary Modifications

- Avoid Trigger Foods:

Certain foods, such as spicy dishes, fatty foods, caffeine, and alcohol, can exacerbate reflux and irritate the esophagus. Identify and eliminate personal triggers to reduce symptoms. - Eat Smaller, More Frequent Meals:

Consuming smaller meals can help reduce pressure on the LES, minimizing the risk of acid reflux. This practice also aids in better digestion and nutrient absorption. - Maintain a Balanced Diet:

A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins supplies essential nutrients that support the esophageal lining and overall digestive health.

Weight Management

- Achieve and Maintain a Healthy Weight:

Excess weight, particularly in the abdominal region, increases pressure on the LES and can worsen GERD symptoms. Regular physical activity and proper nutrition are key to managing weight effectively.

Posture and Sleep Habits

- Elevate the Head of Your Bed:

Elevating the head of your bed by 6–8 inches can help prevent nighttime reflux by reducing the likelihood of acid traveling back into the esophagus. - Stay Upright After Eating:

Avoid lying down immediately after meals. Remaining upright for at least two hours post-eating can help reduce reflux symptoms. - Maintain Good Posture:

Proper posture supports the digestive system and reduces pressure on the esophageal sphincters, contributing to improved esophageal function.

Stress Management

- Practice Relaxation Techniques:

Stress can worsen reflux and other digestive issues. Incorporate stress-reduction practices such as mindfulness, meditation, yoga, or deep-breathing exercises into your routine. - Ensure Adequate Sleep:

Quality sleep is crucial for overall health and healing. Aim for 7–9 hours per night to support proper digestive function and reduce stress.

Avoid Harmful Substances

- Quit Smoking:

Smoking weakens the LES and increases acid production, thereby exacerbating GERD symptoms. Quitting smoking is one of the most beneficial steps for protecting your esophagus. - Limit Alcohol Intake:

Alcohol can irritate the esophageal lining and relax the LES, making it easier for acid to reflux. Moderation is key to maintaining esophageal health.

By embracing these lifestyle practices, you can create a supportive environment for your esophagus, reduce the risk of developing reflux and other conditions, and promote overall digestive wellness.

Trusted Resources & Further Reading

Staying well-informed about esophageal health is essential for both patients and healthcare professionals. Below are some highly regarded resources that offer detailed information, up-to-date research, and practical guidance on maintaining esophageal wellness.

Recommended Books

- “Dropping Acid: The Reflux Diet Cookbook & Cure” by Jamie Koufman and Jordan Stern:

This book provides dietary strategies and recipes designed to manage acid reflux and support esophageal health. - “The Acid Watcher Diet” by Jonathan Aviv:

Offering a comprehensive plan to prevent and heal acid-related conditions, this book emphasizes lifestyle changes and dietary modifications for esophageal protection. - “Esophagus: Anatomy, Functions, and Diseases” by Mark R. Stein:

A detailed exploration of esophageal structure and function, this text covers common disorders and treatment options, making it a valuable resource for both patients and professionals.

Academic Journals

- American Journal of Gastroenterology:

A leading publication in the field of gastroenterology, this journal features the latest research on esophageal disorders, diagnostic techniques, and treatment strategies. - Diseases of the Esophagus:

This peer-reviewed journal focuses exclusively on esophageal health, offering in-depth studies on a variety of conditions affecting the esophagus.

Digital Tools and Mobile Apps

- MyFitnessPal:

This app helps you track your diet and nutritional intake, making it easier to identify and avoid foods that trigger reflux. - Cara Care:

Designed for individuals with digestive disorders, this app provides personalized nutritional guidance and tracks symptoms to help manage conditions like GERD. - Headspace:

A mindfulness and meditation app that offers guided relaxation techniques to reduce stress, which can have a positive impact on digestive health.

These trusted resources provide valuable insights and practical tools to help you manage and maintain esophageal health effectively. Whether you’re a patient seeking to improve your quality of life or a healthcare professional looking for the latest research, these references can serve as reliable guides.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Esophagus

What is the primary function of the esophagus?

The esophagus serves as a muscular tube that transports food and liquids from the mouth to the stomach, utilizing coordinated peristaltic movements and sphincter control to ensure efficient passage and prevent reflux.

How does the esophagus prevent acid reflux?

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) maintains a constant tone, contracting to prevent the backflow of acidic gastric contents. It relaxes only during swallowing, thereby protecting the esophageal lining from acid damage.

What are common disorders of the esophagus?

Common esophageal disorders include GERD, esophageal cancer, achalasia, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophagitis. These conditions can cause symptoms such as heartburn, difficulty swallowing, chest pain, and chronic cough.

How is esophageal function evaluated?

Esophageal function is typically evaluated using endoscopy, barium swallow studies, manometry, pH monitoring, CT scans, MRI, and other specialized tests that assess the structure and motility of the esophagus.

What lifestyle changes can improve esophageal health?

Maintaining a healthy weight, avoiding trigger foods, eating smaller meals, elevating the head during sleep, quitting smoking, and reducing alcohol intake are effective lifestyle modifications to enhance esophageal function and reduce reflux symptoms.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social media platform to help spread awareness about esophageal health and overall digestive wellness.