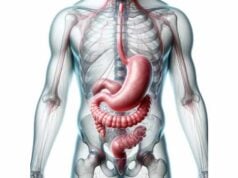

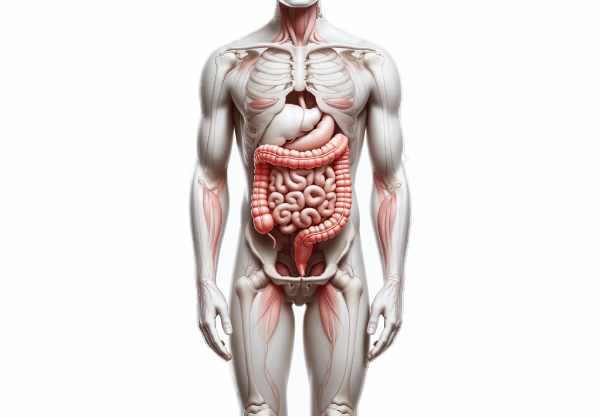

The large intestine is a vital component of the digestive system that plays a key role in processing waste, absorbing water and electrolytes, and maintaining overall digestive health. Despite being shorter than the small intestine, it is wider in diameter and home to a complex community of bacteria that influence immunity, metabolism, and even mood. This guide delves into the large intestine’s detailed anatomy, its physiological roles in water reabsorption, fermentation of indigestible matter, feces formation, and vitamin synthesis, as well as common disorders that affect it, modern diagnostic methods, various treatment options, and lifestyle strategies to help maintain a healthy colon.

Table of Contents

- Anatomy & Structure

- Physiology & Functions

- Common Disorders

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Treatment Options

- Nutritional Strategies & Supplements

- Lifestyle Practices

- Trusted Resources & Further Reading

- Frequently Asked Questions

Anatomy & Structure

The large intestine, also known as the colon, is approximately 1.5 meters long and plays a central role in the final stages of digestion. Its primary segments include the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal, each with specialized functions and structures.

Cecum

The cecum is the pouch-like beginning of the large intestine, situated in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen. It receives chyme from the ileum via the ileocecal valve, which regulates the flow of digested material while preventing backflow. The cecum not only absorbs fluids and salts but also serves as the entry point for the appendix—an organ whose role in immune function is under active study.

Colon

The colon is the longest segment and is subdivided into four main parts:

- Ascending Colon:

Extends upward on the right side of the abdominal cavity from the cecum to the hepatic flexure. This section primarily absorbs water and electrolytes from the chyme, transforming it into a more solid form. - Transverse Colon:

Spanning the width of the abdomen from the hepatic to the splenic flexure, the transverse colon continues the absorption process. It is supported by the transverse mesocolon, which also carries blood vessels that nourish the colon. - Descending Colon:

Travels downward along the left side of the abdomen, storing the formed fecal matter and continuing water absorption. - Sigmoid Colon:

The S-shaped segment connecting the descending colon to the rectum. It stores feces temporarily until the body is ready for defecation, aided by its muscular walls that facilitate peristalsis.

Rectum and Anal Canal

- Rectum:

A straight, muscular tube that follows the sigmoid colon, the rectum stores fecal matter until defecation. Stretch receptors in the rectal walls signal the need to empty the bowels. - Anal Canal:

The final section of the large intestine, the anal canal is approximately 2.5 to 4 centimeters long. It contains two sphincters: an involuntary internal sphincter and a voluntary external sphincter, which work together to control the passage of feces during defecation.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The large intestine receives blood primarily from branches of the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries:

- The Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) supplies the cecum, ascending colon, and most of the transverse colon.

- The Inferior Mesenteric Artery (IMA) supplies the descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum.

Venous blood from these regions drains into the portal vein, which carries nutrient-rich blood to the liver for processing. An extensive network of lymphatic vessels and nodes along the colon plays a crucial role in immune surveillance and fat absorption.

Nervous System and Microbiota

The large intestine is innervated by both the autonomic and enteric nervous systems, with parasympathetic nerves promoting peristalsis and secretion, while sympathetic nerves modulate these processes. Additionally, the colon hosts a vast microbiota—a complex ecosystem of bacteria that aids in fermenting indigestible carbohydrates, synthesizing vitamins, and modulating the immune system. These microbes play an essential role in digestive health and overall well-being.

Physiology & Functions

The large intestine is integral to the final stages of digestion, where it plays several critical roles in maintaining the body’s homeostasis.

Water and Electrolyte Absorption

The primary function of the large intestine is to absorb water and electrolytes from the undigested material (chyme) that enters from the small intestine. Each day, around 1.5 liters of water enter the colon, with 90–95% reabsorbed. This process is essential for preventing dehydration and maintaining a proper balance of fluids and electrolytes in the body. Sodium and chloride ions are also reclaimed, which helps regulate osmotic pressure and blood volume.

Fermentation of Undigested Food

The large intestine is home to an extensive microbiome that ferments indigestible carbohydrates such as dietary fibers and resistant starches. This fermentation process produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like acetate, propionate, and butyrate. These SCFAs serve as energy sources for the colon cells (colonocytes) and have numerous beneficial effects:

- Energy Supply:

SCFAs provide a major energy source for the cells lining the colon, supporting tissue repair and function. - pH Regulation:

The production of SCFAs helps maintain an acidic environment in the colon, which inhibits pathogenic bacteria and supports beneficial microbial populations. - Immune Modulation:

SCFAs influence the immune system by modulating inflammatory responses and enhancing the gut barrier function.

Formation and Storage of Feces

As water and electrolytes are absorbed, the remaining indigestible material is compacted into feces. The colon stores fecal matter temporarily in the sigmoid colon and rectum. When the rectum is full, stretch receptors trigger the urge to defecate, initiating the process of waste elimination through the anal canal.

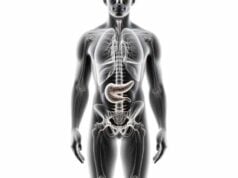

Vitamin Synthesis

Certain beneficial bacteria residing in the large intestine synthesize vitamins, including vitamin K and various B vitamins (such as biotin and folate). These vitamins are absorbed into the bloodstream, contributing to overall nutritional status and supporting critical metabolic functions.

Immunological Functions

The large intestine is a key player in the immune system. It houses gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), which contains immune cells that protect against pathogens. The interaction between the microbiota and the immune system helps maintain a balanced inflammatory response and prevents infections.

Gut-Brain Axis

Emerging research indicates that the large intestine communicates with the central nervous system via the gut-brain axis. The microbiota produces neurotransmitters and other signaling molecules that influence mood, stress response, and overall mental health, underscoring the importance of a healthy colon for both physical and emotional well-being.

Common Disorders

The large intestine can be affected by a variety of disorders, which may impair its function and lead to significant health problems. Early diagnosis and management are critical to preserving colon health.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Overview:

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits (diarrhea, constipation, or a combination of both). Although its exact cause is unclear, stress, diet, and altered gut motility are key contributors. - Symptoms:

Common symptoms include cramping, bloating, and changes in stool frequency or consistency, which often fluctuate over time. - Management:

Treatment strategies include dietary modifications (e.g., low FODMAP diet), stress management techniques, and medications to alleviate symptoms.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBD includes two main conditions: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, both of which involve chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Crohn’s Disease:

Affects any part of the digestive tract, with the ileum and colon being most commonly involved. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue. Inflammation in Crohn’s disease is transmural, potentially leading to fistulas and strictures. - Ulcerative Colitis:

Confined to the colon and rectum, this condition involves continuous inflammation of the mucosal lining. Symptoms include bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and urgency. Chronic inflammation can lead to complications such as colon cancer. - Management:

Treatment options for IBD include anti-inflammatory medications (aminosalicylates, corticosteroids), immunosuppressants, and biologic agents. In severe cases, surgical intervention may be required.

Diverticular Disease

Diverticular disease is characterized by the formation of small pouches (diverticula) in the colon wall. It can be divided into diverticulosis (formation of pouches) and diverticulitis (inflammation of the pouches).

- Diverticulosis:

Usually asymptomatic, but may cause mild discomfort or bloating. - Diverticulitis:

Inflammation of the diverticula can cause severe abdominal pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits. Recurrent diverticulitis may lead to complications such as abscesses or perforations. - Management:

A high-fiber diet, antibiotics, and, in severe cases, surgery to remove the affected section of the colon can help manage diverticular disease.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer often begins as benign polyps that may develop into malignant tumors over time.

- Risk Factors:

Age, family history, a diet high in red and processed meats, smoking, and alcohol consumption increase the risk of colorectal cancer. - Symptoms:

Symptoms include changes in bowel habits, blood in the stool, abdominal pain, and unexplained weight loss. - Management:

Early detection through regular screenings, such as colonoscopies, is critical. Treatment options include surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, depending on the stage of the cancer.

Constipation

Constipation is a common digestive complaint characterized by infrequent or difficult bowel movements, often due to a lack of fiber, dehydration, or a sedentary lifestyle.

- Symptoms:

Straining during bowel movements, hard stools, and a feeling of incomplete evacuation are common in constipation. - Management:

Increasing dietary fiber, staying well-hydrated, engaging in regular physical activity, and, when necessary, using laxatives or stool softeners can help relieve constipation.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is defined by frequent, watery bowel movements, which may result from infections, food intolerances, or chronic conditions like IBS or IBD.

- Symptoms:

Loose stools, abdominal cramps, and urgency are common in diarrhea. - Management:

Treatment includes rehydration, dietary modifications, and medications to reduce stool frequency and manage underlying causes.

Diagnostic Techniques & Evaluation Methods

Accurate diagnosis of large intestine disorders is essential for effective treatment and management. A combination of clinical evaluations, laboratory tests, and imaging techniques is used to assess colon health and identify abnormalities.

Clinical Evaluation

- Medical History and Symptom Assessment:

A detailed history regarding bowel habits, abdominal pain, changes in stool, and family history is crucial for identifying potential issues. - Physical Examination:

The physical exam may include a digital rectal exam (DRE) to assess the rectum and lower colon for abnormalities such as masses, tenderness, or strictures.

Laboratory Tests

- Stool Analysis:

Stool tests, including fecal occult blood tests, help detect hidden blood, signs of infection, or inflammatory markers that may indicate colorectal cancer, IBD, or other disorders. - Blood Tests:

Blood tests such as complete blood count (CBC) and metabolic panels help detect anemia, inflammatory markers, and electrolyte imbalances, providing clues to conditions like IBD or chronic gastrointestinal bleeding.

Imaging Techniques

- Colonoscopy:

Colonoscopy is the gold standard for diagnosing large intestine disorders. It allows for direct visualization of the entire colon, enabling the detection of polyps, tumors, inflammation, and bleeding. Biopsies can be performed during the procedure. - Sigmoidoscopy:

This less invasive procedure examines the sigmoid colon and rectum and is used for screening and diagnosing lower gastrointestinal conditions. - CT Colonography (Virtual Colonoscopy):

A non-invasive imaging technique that uses CT scans to produce detailed images of the colon. It is effective for detecting polyps and tumors, though it may require follow-up colonoscopy for tissue sampling. - Barium Enema:

In this X-ray procedure, the colon is filled with a barium solution to outline its structure, aiding in the detection of strictures, diverticula, and other structural abnormalities. - Abdominal X-Ray:

A basic imaging method that can detect obstructions, perforations, and abnormal gas patterns within the colon.

Advanced Diagnostic Methods

- Capsule Endoscopy:

A capsule containing a camera is swallowed to capture images of the gastrointestinal tract, useful in certain cases when conventional endoscopy cannot access all areas. - Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS):

Combines endoscopy and ultrasound to produce high-resolution images of the colon wall and surrounding tissues, aiding in the evaluation of tumors and inflammatory processes. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI provides detailed images without radiation exposure and is particularly useful for evaluating complex cases such as fistulas or deep infiltrating inflammatory bowel disease.

Biopsy and Histological Examination

During colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy, tissue samples may be collected for histological analysis. Biopsy is critical for diagnosing conditions like IBD, colorectal cancer, and other pathologies by examining the cellular architecture and inflammatory patterns.

Treatment Strategies & Therapeutic Interventions

Treatment for large intestine disorders is tailored to the underlying condition, severity, and patient-specific factors. Strategies range from lifestyle modifications and medications to advanced endoscopic and surgical interventions.

Conservative Management

- Dietary Modifications:

Adopting a high-fiber diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can improve bowel regularity and prevent constipation. In cases of IBS or IBD, avoiding trigger foods and incorporating anti-inflammatory nutrients is key. - Hydration:

Adequate water intake is essential for maintaining stool consistency and supporting overall digestive function. - Regular Physical Activity:

Exercise enhances gut motility, reduces stress, and supports weight management, which are all beneficial for colon health.

Pharmacologic Therapies

- Antibiotics:

Used to treat bacterial infections of the colon, such as those seen in diverticulitis or certain cases of IBD. - Anti-Inflammatory Medications:

Aminosalicylates and corticosteroids reduce inflammation in inflammatory bowel diseases, helping to alleviate pain and other symptoms. - Immunosuppressants and Biologics:

Medications like azathioprine, methotrexate, and biologics (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab) modulate the immune response in conditions like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. - Antispasmodics and Antidiarrheals:

These medications help manage symptoms of IBS and other functional bowel disorders by reducing spasms and regulating bowel movements. - Laxatives and Stool Softeners:

For patients with constipation, these medications help promote regular bowel movements and prevent straining.

Endoscopic Interventions

- Polypectomy:

Removal of polyps during colonoscopy to prevent progression to colorectal cancer. - Endoscopic Dilation:

Used to widen strictures in the colon, improving bowel movements and relieving obstruction. - Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR):

A technique to remove early-stage cancerous or precancerous lesions in the colon without the need for major surgery.

Surgical Options

- Colectomy:

Surgical removal of a portion or the entire colon, performed in cases of severe IBD, colorectal cancer, or complicated diverticulitis. - Ileostomy/Colostomy:

Procedures that divert bowel contents to an external bag, used when resection of the colon is necessary or as a temporary measure in severe disease. - Bowel Resection and Anastomosis:

Removal of diseased bowel segments followed by reconnection of the healthy ends, commonly performed in cancer or severe inflammatory conditions. - Strictureplasty:

A procedure to widen narrowed areas of the colon, particularly useful in Crohn’s disease, to preserve bowel length while alleviating obstructions.

Innovative and Emerging Therapies

- Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT):

FMT involves transferring stool from a healthy donor to a patient to restore the balance of the gut microbiome, showing promise in treating recurrent Clostridium difficile infections and certain cases of IBD. - Stem Cell Therapy:

Research into using stem cells to regenerate damaged intestinal tissues offers potential future treatments for severe IBD and other chronic conditions. - Precision Medicine:

Customizing treatment based on genetic, microbial, and metabolic profiles to optimize therapeutic outcomes and minimize side effects.

Combining these treatment modalities with personalized care strategies allows for the effective management of large intestine disorders, improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Nutritional Strategies & Supplements

A healthy diet and targeted supplementation are fundamental for maintaining large intestine health. The right nutrients support digestive function, promote a balanced gut microbiome, and reduce inflammation.

Dietary Recommendations

- High-Fiber Foods:

A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains promotes regular bowel movements, supports colon health, and reduces the risk of constipation and diverticulitis. - Adequate Hydration:

Drinking sufficient water helps maintain optimal digestion and prevents the formation of hard, dry stools. - Low-Fat, Low-Sugar Diet:

Minimizing intake of processed foods, saturated fats, and refined sugars can reduce inflammation and improve overall digestive health.

Key Supplements

- Probiotics:

Supplementing with beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium supports a healthy gut microbiome, improves digestion, and may alleviate symptoms of IBS and IBD. - Prebiotics:

Non-digestible fibers, such as inulin and fructooligosaccharides, serve as food for beneficial gut bacteria, promoting their growth and activity. - Fiber Supplements:

Psyllium husk and other fiber supplements can increase stool bulk, improve bowel regularity, and alleviate constipation. - Glutamine:

An amino acid that helps repair and maintain the integrity of the intestinal lining, glutamine can reduce inflammation and support overall gut health. - Curcumin:

The active compound in turmeric, curcumin, has potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that may reduce colon inflammation, especially in conditions like IBD. - Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

These essential fats, primarily found in fish oil, help reduce inflammation and may protect against inflammatory conditions of the large intestine. - Aloe Vera:

Known for its soothing properties, aloe vera may help reduce irritation and inflammation in the digestive tract, promoting overall intestinal health.

Integrating these nutritional strategies and supplements into your diet can enhance large intestine function, support a balanced microbiome, and reduce the risk of digestive disorders.

Lifestyle Practices for Intestinal Health

Healthy lifestyle choices are paramount in maintaining the function of the large intestine. Consistent, positive habits not only improve digestion but also support overall well-being.

Physical Activity and Weight Management

- Regular Exercise:

Engaging in regular physical activity, such as walking, cycling, or swimming, stimulates gut motility, helps maintain a healthy weight, and reduces the risk of constipation and diverticular disease. - Weight Control:

Maintaining a healthy weight reduces the strain on your digestive system and lowers the risk of inflammatory bowel disorders and colorectal cancer.

Stress Reduction

- Mindfulness and Relaxation Techniques:

Practices such as yoga, meditation, and deep breathing exercises help reduce stress, which is known to affect gut motility and exacerbate conditions like IBS. - Adequate Sleep:

Getting 7–9 hours of quality sleep each night supports digestive health by allowing the body to repair and maintain its internal systems.

Dietary and Hydration Habits

- High-Fiber Diet:

A diet rich in fiber promotes healthy bowel movements and prevents constipation. Foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains are essential for a healthy colon. - Stay Hydrated:

Drinking plenty of water helps soften stool, facilitates digestion, and aids in the absorption of nutrients. - Limit Processed Foods:

Reducing the intake of highly processed foods, sugary snacks, and saturated fats minimizes inflammation and supports overall digestive health.

Avoiding Harmful Substances

- Reduce Alcohol Intake:

Excessive alcohol can irritate the gut lining and disrupt the microbiome balance. Moderation is key. - Quit Smoking:

Smoking negatively impacts digestive health by impairing blood flow and increasing the risk of colorectal cancer. Quitting smoking can significantly benefit your large intestine.

Regular Medical Check-Ups

- Routine Screenings:

Regular colonoscopies and check-ups can help detect early signs of colorectal cancer, polyps, and other conditions, allowing for timely intervention. - Monitor Digestive Health:

Pay attention to changes in bowel habits, abdominal pain, or unusual symptoms, and consult your healthcare provider for early diagnosis and management.

By adopting these lifestyle practices, you can support your large intestine’s function, enhance digestion, and promote overall gastrointestinal health.

Trusted Resources & Further Reading

Staying well-informed about digestive health is essential for maintaining the function of the large intestine and preventing disease. The following resources offer in-depth information, recent research, and practical strategies to optimize colon health.

Recommended Books

- “Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body’s Most Underrated Organ” by Giulia Enders:

This engaging book explains the complex workings of the digestive system, including the crucial role of the large intestine. - “The Good Gut: Taking Control of Your Weight, Your Mood, and Your Long-Term Health” by Justin and Erica Sonnenburg:

A comprehensive guide on how the gut microbiome affects overall health, with practical advice for maintaining digestive wellness. - “Fiber Fueled: The Plant-Based Gut Health Program for Losing Weight, Restoring Your Health, and Optimizing Your Microbiome” by Will Bulsiewicz:

Focuses on the benefits of a high-fiber diet, emphasizing how fiber can improve colon health and enhance digestive function.

Academic Journals

- Gastroenterology:

A leading journal that publishes cutting-edge research on digestive system disorders, including studies focused on the large intestine. - The American Journal of Gastroenterology:

Provides clinical research and reviews on gastrointestinal health, offering insights into the diagnosis and management of colon disorders.

Mobile Apps

- Cara Care:

An app that helps track digestive symptoms, dietary intake, and lifestyle factors, aiding in the management of conditions like IBS and IBD. - MyFitnessPal:

A nutrition and fitness tracking app that assists with maintaining a balanced diet, essential for digestive and overall health. - Headspace:

A mindfulness and meditation app designed to reduce stress, which can have a beneficial effect on digestive function and overall well-being.

These trusted resources provide valuable information and practical tools to help you manage and improve large intestine health, ensuring a balanced digestive system and overall wellness.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Large Intestine

What is the primary function of the large intestine?

The large intestine absorbs water and electrolytes from indigestible food residue, forming and storing feces. It also plays a vital role in fermenting dietary fibers and supporting a healthy gut microbiome.

How does the large intestine contribute to overall health?

Beyond water absorption and feces formation, the large intestine houses beneficial bacteria that ferment indigestible carbohydrates, produce short-chain fatty acids, synthesize essential vitamins, and modulate the immune system.

What are common conditions affecting the large intestine?

Common disorders include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), diverticular disease, colorectal cancer, constipation, and diarrhea.

How is large intestine health evaluated?

Diagnosis is achieved through a combination of clinical evaluations, laboratory tests (stool and blood tests), imaging techniques (colonoscopy, CT, MRI, barium enema), and sometimes advanced procedures like endoscopic ultrasound.

What lifestyle practices support large intestine health?

A high-fiber diet, adequate hydration, regular physical activity, stress management, and avoiding processed foods are essential for maintaining a healthy large intestine and overall digestive function.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a healthcare provider for personalized guidance.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social media platform to help spread awareness about maintaining a healthy large intestine and overall digestive wellness.