Retinal artery occlusion (RAO) is a serious and potentially vision-threatening ocular condition that occurs when the blood supply to the retina is suddenly cut off, resulting in ischemia (lack of blood flow) and subsequent damage to retinal tissue. The retina is a light-sensitive layer in the back of the eye that converts light into neural signals that the brain processes. The central retinal artery and its branches provide a continuous and sufficient blood supply to the retina, which is critical to its health. When these arteries become clogged, it can cause sudden, painless vision loss that can be partial or complete, depending on the severity of the occlusion.

Types of Retinal Artery Occlusion

RAO is classified into several types based on which part of the retinal arterial system is affected.

- Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO): This is the most severe type of RAO, in which the central retinal artery, the primary artery supplying the retina, becomes clogged. CRAO causes widespread retinal ischemia, which can result in profound and permanent vision loss if not treated promptly.

- Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion (BRAO) is a condition in which one of the smaller branches of the central retinal artery becomes occluded. The extent of vision loss in BRAO is typically less severe than in CRAO, and it is frequently limited to the specific area of the retina served by the affected branch.

- Cilioretinal Artery Occlusion: The cilioretinal artery is a variant artery that supplies blood to the macula—the part of the retina responsible for central vision—in about 20-30% of the population. An occlusion in this artery can cause significant central vision loss, but peripheral vision may remain intact.

Pathophysiology Of Retinal Artery Occlusion

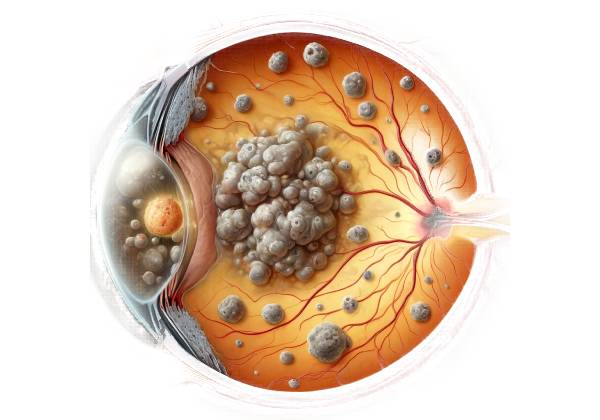

The pathophysiology of RAO involves a sudden interruption of blood flow to the retina, depriving retinal cells of oxygen and essential nutrients. Without adequate blood supply, ischemic damage to retinal tissue occurs within minutes. The retina is extremely metabolically active, and even brief periods of ischemia can cause irreversible damage to the photoreceptors and other retinal cells.

The underlying cause of arterial blockage in RAO is typically an embolus, which is a small particle or plaque that travels through the bloodstream and lodges in the retinal artery. These emboli can come from several sources:

- Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerosis, which is characterized by the accumulation of fatty plaques within the arteries, is a common cause of RAO. These plaques can break off and form emboli, which travel to the retinal artery.

- Cardiac Sources: Emboli can also come from the heart, especially in people who have atrial fibrillation, valvular heart disease, or have suffered a heart attack. These cardiac conditions can cause clots to dislodge and travel to the retinal arteries.

- Carotid Artery Disease: Another common cause of emboli is carotid artery stenosis, a condition in which the carotid arteries that supply blood to the head and neck narrow due to atherosclerosis. Plaques from these arteries can dislodge and travel to the retinal vessels.

RAO can be caused by a variety of factors other than emboli, including:

- Giant Cell Arteritis: This inflammatory condition affects large and medium-sized arteries and can cause occlusion of the central retinal artery. It is considered a medical emergency because it can cause occlusion of the arteries that supply the optic nerve, resulting in blindness.

- Hypercoagulable States: Conditions that raise the risk of blood clotting, such as antiphospholipid syndrome or certain cancers, can also cause RAO.

- Vasospasm: RAO can occur as a result of a spasm of the retinal artery, which temporarily restricts blood flow. This is less common, but can still cause significant vision loss.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors may predispose an individual to developing RAO:

- Age: RAO occurs more frequently in older adults, particularly those over the age of 60. The risk rises with age due to the higher prevalence of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in this population.

- Hypertension: High blood pressure is a major risk factor for RAO because it promotes atherosclerosis and increases the likelihood of plaque rupture and embolus formation.

- Diabetes Mellitus: Diabetes is another significant risk factor because it accelerates the process of atherosclerosis and increases the risk of embolic events.

- Smoking: Smoking is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis, both of which can contribute to RAO.

- Hyperlipidemia: High levels of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood can cause the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, raising the risk of RAO.

- Cardiovascular Disease: People with a history of heart disease, especially those with atrial fibrillation or carotid artery disease, are more likely to develop RAO.

- Family History: A family history of cardiovascular disease or RAO can raise a person’s risk.

Clinical Presentation

RAO’s clinical presentation is typically defined by a sudden onset of painless vision loss in one eye. The severity of vision loss is dependent on the type of RAO and the extent of retinal ischemia:

- CRAO: Patients with CRAO frequently experience a sudden and profound loss of vision in the affected eye, resembling a “curtain falling” over their visual field. The vision loss is usually severe, with visual acuity frequently reduced to counting fingers or worse. Peripheral vision may also be impaired.

- BRAO: Patients with BRAO typically exhibit partial vision loss in the area of the retina supplied by the occluded branch. A specific quadrant of the visual field may experience vision loss.

- Cilioretinal Artery Occlusion: Patients with cilioretinal artery occlusion may lose central vision but retain peripheral vision.

Complications and Prognoses

The prognosis of RAO is largely determined by the timing of treatment and the severity of the ischemic damage. Unfortunately, despite prompt treatment, many patients with CRAO do not fully recover their vision due to the rapid onset of irreversible retinal damage. BRAO has a better prognosis because the ischemic area is more localized, but it can still cause significant visual impairment, especially if the macula is involved.

One of the most serious complications of RAO is neovascularization, which occurs when abnormal blood vessels form in response to ischemia. These vessels can cause additional complications such as vitreous hemorrhage, retinal detachment, and neovascular glaucoma, all of which can result in vision loss or blindness.

RAO is also considered a warning sign of systemic vascular disease. Patients with RAO are more likely to have a stroke, a myocardial infarction, or other serious cardiovascular events. As a result, the occurrence of RAO frequently necessitates an immediate assessment for underlying cardiovascular risk factors and systemic disease.

Diagnostic Tools for Retinal Artery Occlusion

To determine the underlying cause and extent of retinal artery occlusion, a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and occasionally additional tests are required. An accurate and timely diagnosis is critical for initiating treatment and potentially saving vision.

Clinical Evaluation

The first step in diagnosing RAO is to conduct a thorough clinical evaluation that includes a detailed history and an eye examination. During the history-taking procedure, the patient will usually describe a sudden onset of vision loss in one eye. The clinician will ask about any associated symptoms, such as headaches or jaw claudication, which could indicate a condition like giant cell arteritis. The patient’s medical history, including risk factors like hypertension, diabetes, and smoking, is also crucial.

Fundus Examination

A fundus examination with an ophthalmoscope or slit lamp containing a fundus lens is an important part of the clinical evaluation. In cases of CRAO, the retina may appear pale and swollen due to ischemia, with a distinct “cherry-red spot” at the macula. This red spot represents the underlying choroidal circulation, which remains unaffected by the occlusion and contrasts sharply with the pale retina. In BRAO, the retinal pallor is more limited to the area supplied by the occluded branch artery.

Fluorescein angiogram

Fluorescein angiography is an imaging technique that evaluates retinal circulation. After injecting a fluorescent dye into the bloodstream, a series of photographs are taken as the dye moves through the retinal vessels. In cases of RAO, angiography typically reveals delayed or absent filling of the affected artery and its branches. This test is especially useful for distinguishing between CRAO, BRAO, and other conditions that can resemble RAO, such as retinal vein occlusion or optic neuropathy.

Optical Coherence Tomography(OCT)

OCT is a noninvasive imaging test that produces detailed cross-sectional images of the retina. In the acute phase of RAO, OCT may show thickening of the inner retinal layers due to edema. Thinning of the retina may occur as the condition progresses, indicating retinal layer atrophy as a result of the prolonged ischemia. OCT is also useful for determining the involvement of the macula, which is essential for central vision.

Additional Tests

In some cases, additional testing may be required to determine the underlying cause of RAO and the likelihood of systemic complications. These tests can include:

- Carotid Doppler Ultrasound: To assess for carotid artery stenosis, a common source of emboli that can cause retinal artery occlusion. Carotid Doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive test that uses sound waves to visualize the carotid arteries and measure blood flow. It can detect narrowing or blockages in these arteries, requiring additional evaluation or treatment to avoid future embolic events.

- Echocardiography: This imaging test assesses the heart’s structure and function. It can aid in determining potential sources of emboli, such as valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation, or the presence of a cardiac thrombus. Transesophageal echocardiography, a more detailed version of the test, may be used if a cardiac source of emboli is highly suspected.

- Blood Tests: Blood tests may be performed to look for conditions that increase the risk of clot formation, such as hypercoagulability. Coagulation tests, lipid profiles, and inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) may all be performed, which are especially important in suspected cases of giant cell arteritis.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography: These imaging modalities can provide a more detailed assessment of the cerebral and ocular blood vessels. MRI or CT angiography is especially useful when there is a concern about concurrent cerebrovascular disease, such as stroke, which may have similar risk factors and underlying causes to RAO.

Differential Diagnosis

When diagnosing RAO, it is critical to distinguish it from other conditions that can cause sudden vision loss. These conditions include the following:

- Retinal Vein Occlusion: Unlike RAO, retinal vein occlusion usually causes gradual vision loss and can be associated with hemorrhages and cotton wool spots in the retina.

- Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: This condition causes damage to the optic nerve due to insufficient blood flow and can result in sudden vision loss similar to RAO. However, it usually manifests as a pale optic disc rather than the retinal changes seen in RAO.

- Ocular Ischemic Syndrome: Caused by severe carotid artery stenosis, this condition can lead to chronic ischemia of the retina and optic nerve, resulting in progressive vision loss. The fundus examination may reveal mid-peripheral hemorrhages and dilated retinal veins, which distinguishes it from RAO.

Retinal Artery Occlusion Management

Managing retinal artery occlusion (RAO) is difficult and time-sensitive, as the condition can result in permanent vision loss if not treated promptly. The primary goals of management are to restore retinal blood flow, prevent further ischemic damage, and treat the underlying cause to reduce the risk of future events.

Immediate interventions

Immediate treatment is critical, particularly for central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO), where the window for potential vision-saving interventions is extremely narrow—often within the first 90 to 120 minutes of symptom onset. While the efficacy of these interventions varies, they all aim to dislodge the occlusion and restore blood flow.

- Ocular Massage: This manual technique involves intermittent pressure on the eye to help dislodge the embolus that is causing the occlusion. The goal is to cause fluctuations in intraocular pressure that will encourage the embolus to move downstream, where it can cause less severe damage or dissolve.

- Anterior Chamber Paracentesis: This procedure removes a small amount of aqueous humor from the anterior chamber of the eye. The goal is to rapidly reduce intraocular pressure, which may increase perfusion to the retina and dislodge the embolus.

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) entails breathing pure oxygen in a pressurized chamber, which can increase oxygen delivery to the retina even when there is an arterial blockage. HBOT may be especially beneficial if administered early in the course of CRAO.

- Inhalation of Carbogen Gas: Carbogen is a 95% oxygen/5% carbon dioxide mixture. Inhaling this gas mixture has the potential to dilate retinal vessels and increase retinal blood flow. However, its effectiveness remains debatable, and it is not widely used.

Medical Management

In addition to immediate interventions, medical management aims to prevent further damage and address the root cause of RAO.

- Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Therapy: To reduce the risk of further embolic events, antiplatelet agents such as aspirin, anticoagulants such as warfarin, or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) may be prescribed, particularly if the emboli originate in the heart, such as atrial fibrillation.

- Thrombolytic Therapy: Although more commonly used in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke, thrombolytic agents such as tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) have been studied for use in CRAO. However, the results have been mixed, and this approach remains controversial due to the potential risks, which include hemorrhagic complications.

- Systemic Corticosteroids: In cases where RAO is associated with giant cell arteritis, high-dose systemic corticosteroids are the primary treatment. Corticosteroids administered promptly can prevent further vascular occlusions and protect against vision loss in the other eye.

- Treatment of Underlying Conditions: Managing conditions that predispose people to RAO, such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, is critical. This may include lifestyle changes, medications, and regular monitoring to reduce the risk of recurrent RAO or other cardiovascular events.

Surgical and Laser Interventions

In some cases, more invasive procedures may be necessary to treat RAO or its complications.

- Laser Photocoagulation: If RAO results in neovascularization, laser photocoagulation may be used to prevent the formation of new, fragile blood vessels that could lead to complications like vitreous hemorrhage or neovascular glaucoma.

- Vitrectomy: When RAO causes serious complications like vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment, a vitrectomy—a surgical procedure to remove the vitreous gel and address the underlying problem—may be required.

- Carotid Endarterectomy or Stenting: Patients with significant carotid artery stenosis may benefit from carotid endarterectomy (surgical removal of the plaque) or carotid stenting (placement of a stent to keep the artery open) to prevent future embolic events, such as RAO.

Long-term management and monitoring

Long-term management of RAO entails close monitoring and secondary prevention to lower the risk of recurrence and other vascular events like stroke or myocardial infarction. Patients with RAO should have regular check-ups with their ophthalmologist and primary care physician or cardiologist to manage risk factors and watch for complications.

In addition to medical treatments, lifestyle changes such as quitting smoking, eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and controlling blood pressure and cholesterol levels are critical components of comprehensive RAO management.

Trusted Resources and Support

Books

- “Retinal Vascular Disease” by Alan J. Ruby and Jay S. Duker – A comprehensive resource on the diagnosis and management of retinal vascular conditions, including RAO.

- “Ophthalmology” by Myron Yanoff and Jay S. Duker – This textbook offers in-depth coverage of various eye conditions, with a detailed section on retinal artery occlusion.

Organizations

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) – The AAO provides extensive resources, guidelines, and patient education materials on retinal artery occlusion and other ocular conditions.

- National Eye Institute (NEI) – The NEI offers a wealth of information on eye health, including research and resources on retinal artery occlusion and related vascular conditions.