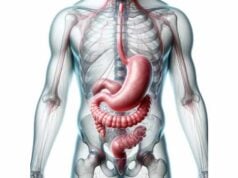

The small intestine is a remarkable organ that plays a critical role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients. As the primary site for nutrient uptake, it transforms ingested food into essential building blocks for the body while supporting immune defense and maintaining overall gastrointestinal health. This guide provides an in-depth exploration of the small intestine’s intricate anatomy, its multifaceted functions, common disorders that affect its performance, and a range of treatment options and lifestyle tips to maintain its optimal function. Whether you are a student, healthcare professional, or simply interested in understanding how your body works, this comprehensive resource offers expert insights into one of the most essential organs of the digestive system.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Overview & Histology

- Physiological Functions & Processes

- Common Disorders & Conditions

- Diagnostic Methods & Procedures

- Therapeutic Approaches & Treatments

- Nutritional Support & Supplementation

- Preventative Care & Healthy Practices

- Trusted Resources & Further Reading

- Frequently Asked Questions

Anatomical Overview & Histology

The small intestine is a long, coiled tube that is essential for digestion and nutrient absorption. It is anatomically divided into three distinct segments—the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum—each with specialized structures that optimize its digestive and absorptive functions.

Segmentation of the Small Intestine

Duodenum

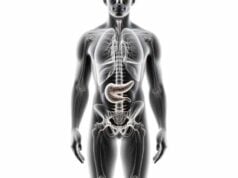

- Location & Structure: The duodenum is the first segment of the small intestine, measuring about 10–12 inches in length. It forms a C-shaped loop around the head of the pancreas.

- Function: It receives chyme from the stomach and mixes it with bile from the liver and digestive enzymes from the pancreas, initiating the chemical breakdown of food and neutralizing stomach acid.

Jejunum

- Location & Structure: The jejunum is the middle segment, approximately 8 feet long, located between the duodenum and the ileum. Its inner surface is highly folded, forming numerous villi and microvilli that drastically increase the surface area available for nutrient absorption.

- Function: This segment is the primary site for the absorption of carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins, and minerals into the bloodstream.

Ileum

- Location & Structure: The ileum is the final segment, the longest part of the small intestine at around 12 feet, and connects to the large intestine at the ileocecal valve.

- Function: The ileum specializes in absorbing bile acids, vitamin B12, and any remaining nutrients, while also playing an important role in immune surveillance via Peyer’s patches—aggregated lymphoid nodules.

Layers of the Small Intestine

The wall of the small intestine is composed of four main layers, each contributing to its complex functions:

- Mucosa:

- Epithelium: The innermost lining comprises a single layer of columnar epithelial cells (enterocytes) that absorb nutrients, along with goblet cells that secrete mucus and enteroendocrine cells that produce digestive hormones.

- Lamina Propria: A loose connective tissue rich in blood vessels, lymphatics, and immune cells supports the epithelium.

- Muscularis Mucosae: A thin layer of smooth muscle aids in local movements of the mucosal layer.

- Submucosa:

- A dense connective tissue layer that houses larger blood vessels, lymphatics, and the submucosal (Meissner’s) plexus, which plays a role in regulating intestinal secretions and blood flow.

- Muscularis Externa:

- Consists of an inner circular muscle layer and an outer longitudinal muscle layer. These layers, controlled by the myenteric (Auerbach’s) plexus, generate peristaltic and segmental movements that propel and mix intestinal contents.

- Serosa:

- The outermost layer is a thin, smooth membrane (visceral peritoneum) that provides a frictionless surface, facilitating the movement of the small intestine against surrounding organs.

Specialized Structures

- Villi and Microvilli:

The mucosal surface is extensively folded into finger-like projections called villi, which further contain microvilli forming a brush border. These structures exponentially increase the surface area, enabling efficient nutrient absorption. - Crypts of Lieberkühn:

Tubular glands located at the base of the villi that contain stem cells for continuous epithelial renewal. They also secrete digestive enzymes and antimicrobial peptides, contributing to gut immunity. - Brunner’s Glands:

Located in the duodenum’s submucosa, these glands secrete an alkaline mucus that neutralizes stomach acid, protecting the intestinal lining and optimizing enzyme activity. - Peyer’s Patches:

Aggregated lymphoid nodules in the ileum that are key for immune surveillance and the generation of immune responses against intestinal pathogens.

Blood Supply and Innervation

- Arterial Supply:

The small intestine is predominantly supplied by branches of the superior mesenteric artery, ensuring a rich blood flow necessary for its high metabolic activity. - Venous Drainage:

Blood from the small intestine drains into the superior mesenteric vein, which joins the splenic vein to form the hepatic portal vein, directing nutrient-rich blood to the liver. - Lymphatic System:

Lacteals in the villi absorb dietary fats, transporting them as chyle through the lymphatic system into the bloodstream. - Nervous Supply:

The enteric nervous system, comprising the submucosal and myenteric plexuses, governs intestinal motility and secretory functions, while extrinsic autonomic nerves modulate these processes further.

Physiological Functions & Processes

The small intestine is indispensable for digestion and nutrient absorption, serving as the primary site for the chemical breakdown of food and uptake of essential nutrients.

Digestion

- Enzymatic Breakdown:

The small intestine receives pancreatic enzymes (amylase, lipase, proteases) and bile from the liver to digest carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Brush border enzymes in the microvilli further break down nutrients into absorbable molecules. - Chemical Digestion:

The duodenum plays a crucial role in neutralizing stomach acid, ensuring that digestive enzymes function optimally.

Nutrient Absorption

- Maximizing Surface Area:

The extensive network of villi and microvilli maximizes the absorptive area, allowing for the efficient uptake of monosaccharides, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals. - Water and Electrolyte Absorption:

The small intestine also absorbs water and electrolytes, ensuring fluid balance and proper hydration. - Transport Mechanisms:

Specialized transport proteins in the enterocytes facilitate active and passive transport of nutrients into the bloodstream.

Immune Function

- Barrier and Surveillance:

The mucosal lining and Peyer’s patches serve as a frontline defense against ingested pathogens. Immune cells within the lamina propria and crypts detect and respond to harmful antigens. - Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT):

Integral to the immune function of the small intestine, GALT plays a crucial role in developing systemic immune responses.

Hormonal Regulation

- Enteroendocrine Signaling:

The small intestine’s enteroendocrine cells secrete hormones such as cholecystokinin (CCK), secretin, and gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP). These hormones regulate digestive enzyme secretion, bile release, and modulate gastric motility. - Feedback Mechanisms:

These hormones also signal satiety and regulate metabolic processes, linking gastrointestinal function to overall energy homeostasis.

Motility and Peristalsis

- Peristaltic Movements:

Coordinated muscle contractions in the muscularis externa propel chyme along the small intestine, ensuring that food is mixed with digestive juices and that nutrients are absorbed efficiently. - Segmentation:

Localized contractions help mix the intestinal contents, optimizing contact with the absorptive surface and enhancing nutrient uptake.

Metabolic and Excretory Functions

- Nutrient Metabolism:

Absorbed nutrients are transported via the hepatic portal vein to the liver, where they are metabolized and distributed throughout the body. - Excretion:

The small intestine contributes to excretion by absorbing water and electrolytes, while the residual waste is eventually passed to the large intestine for elimination.

Common Disorders & Conditions

Various conditions can affect the small intestine, impairing its ability to digest and absorb nutrients, and ultimately affecting overall health. Here are some of the most common disorders:

Celiac Disease

- Overview:

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by the ingestion of gluten, leading to damage of the intestinal villi and malabsorption of nutrients. - Symptoms:

Diarrhea, bloating, weight loss, fatigue, and, in some cases, dermatitis herpetiformis. - Management:

A lifelong gluten-free diet is the mainstay of treatment, alongside nutritional supplementation to correct deficiencies.

Crohn’s Disease

- Overview:

Crohn’s disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that often affects the ileum but can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract. - Symptoms:

Abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue. Complications may include strictures, fistulas, and abscesses. - Management:

Involves anti-inflammatory medications, immunosuppressants, antibiotics, biologics, and sometimes surgery to remove diseased segments.

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- Overview:

SIBO occurs when excessive bacteria grow in the small intestine, leading to malabsorption and gastrointestinal symptoms. - Symptoms:

Bloating, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and nutrient malabsorption. - Management:

Typically treated with antibiotics, dietary modifications (such as a low FODMAP diet), and prokinetic agents to improve intestinal motility.

Lactose Intolerance

- Overview:

Lactose intolerance results from a deficiency in lactase, the enzyme responsible for digesting lactose found in dairy products. - Symptoms:

Bloating, diarrhea, gas, and abdominal pain after consuming dairy. - Management:

Avoidance of lactose-containing foods, use of lactase supplements, or switching to lactose-free dairy alternatives.

Intestinal Obstruction

- Overview:

An intestinal obstruction is a blockage that prevents the normal passage of chyme, leading to severe complications. - Symptoms:

Severe abdominal pain, vomiting, bloating, and an inability to pass gas or stool. - Management:

Often requires hospitalization for bowel rest, nasogastric decompression, and, in many cases, surgical intervention to remove or bypass the obstruction.

Celiac Sprue (Tropical Sprue)

- Overview:

A malabsorption disorder that can mimic celiac disease, though its etiology may be linked to infectious agents or nutritional deficiencies. - Symptoms:

Chronic diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption of vitamins and minerals, and anemia. - Management:

Often treated with antibiotics, nutritional supplements, and dietary modifications to improve absorption.

Cystic Fibrosis

- Overview:

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder affecting exocrine glands, leading to thick, sticky mucus that can obstruct the small intestine. - Symptoms:

Intestinal obstruction, malabsorption, and steatorrhea, along with respiratory complications. - Management:

Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy, high-calorie diets, and CFTR modulators to improve protein function. - Multidisciplinary Care:

Involves respiratory, nutritional, and gastroenterological management to address systemic manifestations.

Diagnostic Methods & Assessments

Accurate diagnosis of small intestine disorders involves a comprehensive approach combining clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, imaging studies, and endoscopic procedures.

Clinical Evaluation

- Medical History:

A detailed history of gastrointestinal symptoms, dietary habits, family history, and prior treatments is essential. - Physical Examination:

Abdominal palpation and examination can reveal tenderness, distension, or masses indicative of underlying pathology.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Detects anemia or infection.

- Electrolyte Panel: Assesses for imbalances.

- Celiac Disease Panel: Includes tTG-IgA and EMA tests to confirm gluten sensitivity.

- Nutritional Markers: Levels of iron, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and folate help assess malabsorption.

- Stool Tests:

- Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT): Detects hidden blood.

- Fecal Fat Test: Measures fat content in the stool to diagnose malabsorption disorders.

- Stool Culture: Identifies pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites.

Imaging Studies

- Abdominal X-ray:

Can reveal signs of obstruction, perforation, or abnormal gas patterns. - Ultrasound:

Useful for detecting structural abnormalities, such as masses or fluid collections. - CT Enterography:

Provides detailed cross-sectional images of the small intestine, aiding in the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, tumors, and obstructions. - MR Enterography:

Uses MRI to produce high-resolution images of the small intestine without radiation exposure.

Endoscopic Procedures

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD):

A flexible endoscope is used to examine the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum; biopsies can be taken for histological analysis. - Capsule Endoscopy:

Involves swallowing a small camera that captures images throughout the small intestine, useful for detecting obscure bleeding and inflammatory lesions. - Double Balloon Enteroscopy:

Allows for deep insertion into the small intestine, providing direct visualization, biopsy, and treatment of lesions.

Specialized Testing

- Breath Tests:

- Lactose Breath Test: Assesses for lactose intolerance by measuring hydrogen levels after lactose ingestion.

- SIBO Breath Test: Measures hydrogen and methane levels to diagnose small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

- Biopsy and Histology:

Tissue samples obtained during endoscopy are examined microscopically to diagnose conditions such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, and intestinal neoplasms. - Functional Tests:

- Motility Studies: Evaluate the movement of the small intestine.

- Nutrient Absorption Tests: Assess the efficiency of nutrient uptake.

Therapeutic Approaches & Treatments

Treatment for small intestine disorders is highly individualized, often involving a combination of dietary modifications, medications, endoscopic procedures, and surgery. The following outlines therapeutic approaches for common conditions affecting the small intestine.

Management of Celiac Disease

- Gluten-Free Diet:

The cornerstone of treatment is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet to allow intestinal healing and prevent further damage. - Nutritional Supplementation:

Supplement deficiencies in iron, calcium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and folate as needed. - Medications:

In cases of severe inflammation or during dietary non-compliance, corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents may be prescribed.

Treatment of Crohn’s Disease

- Pharmacotherapy:

- Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Mesalamine and sulfasalazine help reduce intestinal inflammation.

- Corticosteroids: Used for short-term relief during acute flare-ups.

- Immunosuppressants: Azathioprine and methotrexate reduce immune-mediated inflammation.

- Biologics: TNF inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab) and integrin inhibitors (vedolizumab) are effective for moderate to severe disease.

- Surgical Intervention:

Resection of diseased segments or stricturoplasty may be required in cases of complications such as obstruction, fistulas, or abscesses. - Nutritional Therapy:

Special diets, including exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN), can induce remission, particularly in pediatric patients.

Management of SIBO

- Antibiotics:

Short-term courses of antibiotics like rifaximin or metronidazole are commonly used. - Dietary Modifications:

A low FODMAP diet helps minimize fermentable substrates that encourage bacterial overgrowth. - Prokinetics:

Medications that enhance gut motility may be beneficial in preventing recurrence.

Treatment of Lactose Intolerance

- Dietary Avoidance:

Reducing or eliminating lactose-containing foods is the primary strategy. - Lactase Enzyme Supplements:

These supplements can be taken before consuming dairy to improve digestion. - Lactose-Free Alternatives:

Incorporate lactose-free dairy products into your diet.

Management of Intestinal Obstruction

- Conservative Management:

In partial obstructions, treatment may include bowel rest, nasogastric decompression, and intravenous fluids. - Surgical Intervention:

Complete obstructions or those unresponsive to conservative measures require surgical resolution to remove or bypass the blockage.

Treatment for Cystic Fibrosis

- Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy (PERT):

Enzyme supplements aid in the digestion of nutrients. - Nutritional Support:

High-calorie, high-fat diets with fat-soluble vitamin supplements (A, D, E, K) are essential. - CFTR Modulators:

Medications like ivacaftor improve the function of the defective CFTR protein. - Multidisciplinary Care:

Involves respiratory, nutritional, and gastroenterological management to address systemic manifestations.

Nutritional Support & Supplementation

Optimizing the health of the small intestine relies heavily on proper nutrition and supplementation. A balanced diet provides the necessary macronutrients and micronutrients for intestinal repair and function, while targeted supplements can help address specific deficiencies and support gut health.

Dietary Recommendations

- High-Fiber Foods:

Fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains promote healthy digestion and regular bowel movements. - Lean Proteins:

Sources such as poultry, fish, tofu, and legumes support tissue repair and regeneration. - Healthy Fats:

Incorporate omega-3 fatty acids from fish and flaxseed oil to reduce inflammation and support cellular health. - Probiotic-Rich Foods:

Yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and other fermented foods help maintain a balanced gut microbiome. - Hydration:

Adequate water intake is crucial for nutrient absorption and maintaining intestinal motility.

Essential Supplements

- Probiotics:

Enhance gut flora balance and improve intestinal barrier function, which is particularly beneficial in conditions like SIBO and IBS. - Digestive Enzymes:

Supplementation with enzymes can aid in the breakdown of macronutrients, enhancing nutrient absorption especially in individuals with pancreatic insufficiency. - Glutamine:

This amino acid supports the repair of the intestinal lining and is beneficial in inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease and celiac disease. - Vitamin D:

Supports immune function and intestinal health; deficiency is common in inflammatory bowel diseases. - Zinc:

Plays a critical role in immune function and wound healing, aiding in the repair of the intestinal mucosa. - Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

Anti-inflammatory properties reduce intestinal inflammation and support overall gut health. - Aloe Vera:

Known for its soothing and anti-inflammatory effects, aloe vera may help repair and protect the intestinal lining. - Curcumin:

Offers potent anti-inflammatory benefits that can help manage chronic intestinal inflammation. - Peppermint Oil:

Helps alleviate intestinal spasms and discomfort associated with IBS. - Fiber Supplements:

Soluble fibers like psyllium husk support regular bowel movements and improve overall gut function.

Preventative Care & Healthy Practices

Proactive measures and lifestyle modifications can significantly enhance small intestinal health and prevent the onset or progression of various disorders.

Dietary and Lifestyle Modifications

- Balanced, Nutrient-Rich Diet:

Emphasize whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains to provide essential nutrients and antioxidants. - Hydration:

Drinking sufficient water supports digestion and nutrient absorption. - Regular Physical Activity:

Exercise enhances blood flow, promotes intestinal motility, and helps manage weight. - Manage Stress:

Chronic stress can negatively impact gut function. Techniques like meditation, yoga, and deep breathing are beneficial. - Adequate Sleep:

Quality sleep supports the body’s repair mechanisms and hormonal balance, essential for intestinal health. - Avoid Processed Foods:

Limiting processed and high-fat foods helps reduce intestinal inflammation and supports optimal digestion.

Routine Health Practices

- Regular Medical Check-ups:

Periodic evaluations by healthcare professionals can help detect gastrointestinal issues early. - Monitoring Symptoms:

Keep track of changes in bowel habits, abdominal pain, and other digestive symptoms to address issues promptly. - Judicious Use of Antibiotics:

Overuse of antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiota; use them only when necessary. - Personalized Diet Plans:

For those with chronic conditions like celiac disease or IBS, a tailored diet (e.g., gluten-free or low FODMAP) is essential.

Mindful Eating Practices

- Chew Thoroughly:

Proper chewing aids digestion by increasing the surface area of food, making it easier for enzymes to act. - Eat Slowly:

Taking time to eat allows for better digestion and reduces the risk of overeating. - Regular Meal Times:

Consistent eating schedules help regulate the digestive system and maintain a healthy circadian rhythm.

Trusted Resources & Further Reading

For more comprehensive insights and the latest research on small intestine health, consider the following trusted resources:

Books

- “Gastrointestinal Physiology” by Leonard R. Johnson:

Offers detailed explanations of digestive processes and the role of the small intestine in nutrient absorption. - “The Enteric Nervous System” by Michael D. Gershon:

Explores the complex neural control of the digestive tract, including the small intestine. - “Celiac Disease: A Hidden Epidemic” by Peter H.R. Green and Rory Jones:

Provides an in-depth look at celiac disease, its diagnosis, and management, emphasizing the importance of small intestinal health.

Academic Journals

- Gastroenterology:

A leading journal publishing cutting-edge research on all aspects of the digestive system, including small intestine function and diseases. - American Journal of Gastroenterology:

Features clinical studies and reviews on digestive disorders, offering insights into diagnostic and treatment approaches. - Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis:

Focuses on inflammatory bowel diseases, including research on Crohn’s disease and related small intestine conditions.

Mobile Apps

- MySymptoms Food Diary:

An app that helps track dietary intake and gastrointestinal symptoms to identify potential triggers for small intestine disorders. - Cara Care:

Provides personalized nutritional advice and symptom tracking for managing digestive health. - Monash University FODMAP Diet:

Offers guidance on following a low FODMAP diet, which is beneficial for conditions like IBS and SIBO.

Frequently Asked Questions on the Small Intestine

What is the primary function of the small intestine?

The small intestine is responsible for digesting food and absorbing nutrients, including carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals, into the bloodstream, while also playing a key role in water and electrolyte absorption.

How does the small intestine facilitate nutrient absorption?

Its highly folded mucosa, with villi and microvilli, increases the surface area for absorption, enabling efficient uptake of digested nutrients through specialized transport mechanisms.

What are common disorders affecting the small intestine?

Common conditions include celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), lactose intolerance, intestinal obstruction, and malabsorption syndromes such as cystic fibrosis.

How is celiac disease diagnosed?

Celiac disease is typically diagnosed through blood tests for specific antibodies (tTG-IgA, EMA) followed by an endoscopic small intestinal biopsy to confirm villous atrophy.

What lifestyle changes support small intestinal health?

A balanced, nutrient-rich diet, proper hydration, regular exercise, stress management, and avoiding processed foods, along with individualized dietary plans, are key to maintaining small intestinal health.

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a healthcare provider for any concerns regarding your health.

Please share this article on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social media platform to help spread awareness about small intestine health and modern treatment strategies.