The stomach is a vital organ in the digestive system, responsible for breaking down food both mechanically and chemically. Acting as a temporary storage reservoir, it churns ingested food and mixes it with potent gastric juices, preparing a semi-liquid substance called chyme for further digestion in the small intestine. In addition to its key role in digestion, the stomach also protects the body from pathogens by maintaining an acidic environment. Understanding its structure, functions, and common disorders is essential for optimal digestive health. This comprehensive guide provides an in-depth look into stomach anatomy, physiology, prevalent conditions, treatment options, and practical tips for maintaining a healthy digestive system.

Table of Contents

- Anatomical Structure

- Gastric Wall Layers

- Gastric Glands & Secretions

- Blood Supply & Innervation

- Digestive and Protective Functions

- Hormonal Regulation

- Interaction with Other Organs

- Common Stomach Conditions

- Diagnostic Methods

- Treatment Options

- Supplements for Stomach Health

- Lifestyle and Dietary Guidelines

- Trusted Resources

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Disclaimer & Sharing

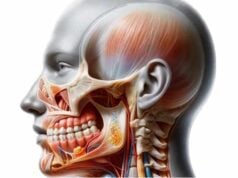

Anatomical Structure of the Stomach

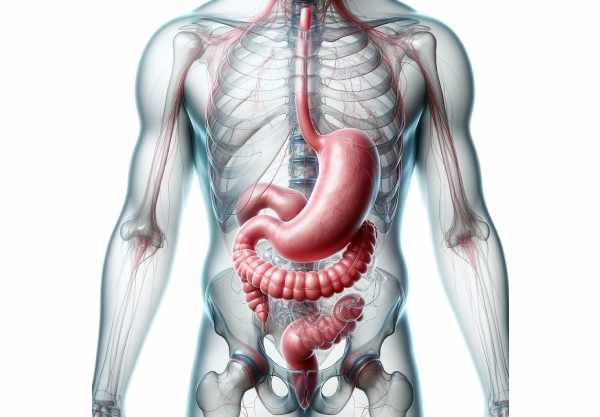

The stomach is a hollow, muscular organ with a distinctive J-shape that bridges the esophagus and the small intestine. Its structure is designed to maximize the efficiency of both mechanical and chemical digestion. Divided into several regions—the cardia, fundus, body (corpus), antrum, and pylorus—each segment plays a unique role in processing ingested food. The cardia, located near the junction with the esophagus, houses the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) that prevents reflux. The fundus acts as a reservoir for ingested food and gas, while the body and antrum are responsible for churning and mixing the food with digestive juices. Finally, the pylorus regulates the release of chyme into the duodenum, ensuring a steady flow of partially digested food for further processing.

Gastric Wall Layers

The stomach wall comprises several layers that work together to protect the organ and facilitate digestion. These layers, each with specialized functions, include:

- Mucosa:

The innermost lining, consisting of epithelial cells that secrete mucus, gastric acid, and digestive enzymes. The mucosa contains gastric pits and glands that produce vital components of gastric juice. - Submucosa:

A supportive layer of connective tissue beneath the mucosa, rich in blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics that nourish and support the mucosal layer. - Muscularis Externa:

A robust layer of smooth muscle responsible for the stomach’s motility. It is subdivided into three layers: - Oblique Layer: The innermost layer that enhances the stomach’s churning ability.

- Circular Layer: Encircles the stomach to help segment and propel the food.

- Longitudinal Layer: The outer layer that contributes to overall contraction and relaxation.

- Serosa:

The outermost covering, a thin layer of connective tissue that forms a smooth, friction-reducing surface to protect the stomach and allow it to glide against adjacent organs.

Gastric Glands & Secretions

Within the mucosal layer of the stomach, specialized gastric glands secrete a variety of substances crucial for digestion. These secretions create an acidic environment that aids in food breakdown and protects the body from pathogens.

- Parietal Cells:

Located primarily in the fundus and body, these cells secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl), which lowers the stomach’s pH, and intrinsic factor, essential for vitamin B12 absorption. - Chief Cells:

Also found in the fundus and body, chief cells produce pepsinogen, an inactive enzyme that is converted to pepsin in the presence of acid. Pepsin initiates protein digestion by breaking down proteins into smaller peptides. - Mucous Cells:

Distributed throughout the stomach, these cells secrete mucus and bicarbonate. Mucus protects the stomach lining from the corrosive effects of acid, while bicarbonate helps neutralize acid near the mucosal surface. - G Cells:

Predominantly located in the antrum, G cells produce gastrin, a hormone that stimulates acid secretion and enhances gastric motility. - D Cells:

Scattered among the gastric glands, D cells secrete somatostatin, a hormone that inhibits the release of gastrin and regulates acid production, maintaining a balanced gastric environment.

Blood Supply & Innervation

The stomach’s functionality depends on an intricate network of blood vessels and nerves that support its operations and coordinate its activities.

- Blood Supply:

The stomach receives blood primarily from branches of the celiac trunk, including: - Left Gastric Artery: Supplies the upper part of the stomach.

- Right Gastric Artery: Supplies the lower portion along the lesser curvature.

- Left Gastroepiploic Artery: Supplies the greater curvature.

- Right Gastroepiploic Artery: Also supplies the greater curvature.

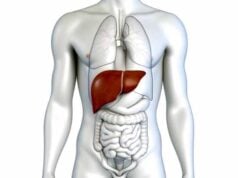

Venous blood from the stomach drains into the portal vein, which carries nutrient-rich blood to the liver for further processing. - Innervation:

The stomach is innervated by both the autonomic and enteric nervous systems: - Sympathetic Innervation: Via the celiac plexus, these fibers inhibit gastric motility and secretion during stress.

- Parasympathetic Innervation: The vagus nerve stimulates gastric motility and secretion, aiding digestion.

- Enteric Nervous System: This intrinsic network of neurons independently regulates many aspects of stomach function, including smooth muscle contractions and secretory activities.

Digestive and Protective Functions

The stomach plays a pivotal role in digestion by performing both mechanical and chemical processes to break down food. Additionally, it serves as a protective barrier against ingested pathogens.

Mechanical Digestion

- Churning Action:

The stomach’s muscular contractions (peristalsis) mix ingested food with gastric juices, mechanically breaking down large food particles into a semi-liquid substance called chyme. - Food Storage:

The stomach temporarily stores food, allowing gradual release into the small intestine, ensuring that the digestive process is not overwhelmed.

Chemical Digestion

- Acid Secretion:

Hydrochloric acid, secreted by parietal cells, lowers the stomach’s pH, activating digestive enzymes like pepsinogen into pepsin, which breaks down proteins. - Enzymatic Breakdown:

Enzymes produced by chief cells, such as pepsin, catalyze the digestion of proteins into smaller peptides. Gastric lipase further aids in the digestion of fats.

Protective Mechanisms

- Acid Barrier:

The low pH in the stomach serves as a barrier to pathogens, killing many bacteria and viruses before they can enter the intestines. - Mucosal Defense:

Mucus, secreted by mucous cells, forms a protective layer that shields the stomach lining from the corrosive effects of gastric acid and digestive enzymes. - Bicarbonate Secretion:

Bicarbonate neutralizes acid at the mucosal surface, maintaining a safe pH for the stomach lining.

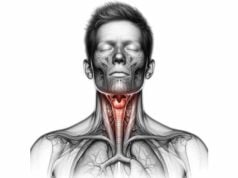

Hormonal Regulation of Gastric Function

Hormones play a critical role in regulating the stomach’s digestive processes. These chemical messengers adjust the secretion of acids, enzymes, and motility to ensure efficient digestion and nutrient absorption.

- Gastrin:

Secreted by G cells in the antrum, gastrin stimulates parietal cells to produce hydrochloric acid and promotes gastric motility. Its release is triggered by the presence of food and distension of the stomach wall. - Somatostatin:

Released by D cells, somatostatin serves as an inhibitor of gastrin. It prevents excessive acid secretion by dampening the activity of parietal cells, thus maintaining a balanced environment within the stomach. - Ghrelin:

Often referred to as the “hunger hormone,” ghrelin is produced by the stomach and signals the brain to increase appetite. It plays a key role in regulating food intake and energy homeostasis.

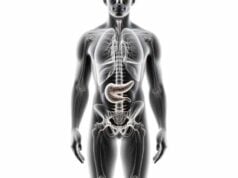

Interaction with Other Digestive Organs

The stomach is not an isolated organ; it works in concert with other parts of the digestive system to ensure the efficient breakdown and absorption of nutrients.

- Duodenal Communication:

The pyloric sphincter regulates the passage of chyme into the duodenum, where digestive enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver further digest fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. - Pancreatic and Hepatic Coordination:

Hormonal signals from the stomach, such as gastrin and cholecystokinin (CCK), coordinate the release of digestive juices from the pancreas and bile from the liver. - Enteric Nervous System:

The intrinsic neural network of the stomach communicates with the entire gastrointestinal tract, synchronizing motility and ensuring that digestive processes occur in a coordinated manner.

Common Stomach Conditions

A variety of disorders can affect the stomach, each with its own set of symptoms and treatment strategies. Understanding these conditions is crucial for timely diagnosis and effective management.

Gastritis

Gastritis is the inflammation of the stomach lining, which can be acute or chronic.

- Causes:

Infections (especially H. pylori), chronic use of NSAIDs, excessive alcohol consumption, and stress can all lead to gastritis. - Symptoms:

Common signs include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bloating, and indigestion. Severe cases may result in bleeding, evidenced by black tarry stools. - Treatment:

Management focuses on eradicating H. pylori with antibiotics, reducing acid production using PPIs or H2 blockers, and lifestyle modifications to avoid irritants.

Peptic Ulcers

Peptic ulcers are open sores that develop on the inner lining of the stomach or the duodenum.

- Etiology:

The majority of ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection or long-term NSAID use, which erodes the protective mucosal lining. - Symptoms:

Patients often experience burning stomach pain, particularly when the stomach is empty, along with bloating, heartburn, and in severe cases, bleeding. - Treatment:

Treatment involves a combination of antibiotics, acid-suppressing medications (PPIs or H2 blockers), and lifestyle modifications to reduce gastric irritation.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

GERD is a chronic condition characterized by the reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus.

- Mechanism:

A weak lower esophageal sphincter (LES) allows acid to escape from the stomach, leading to irritation of the esophageal lining. - Symptoms:

Common symptoms include heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, and difficulty swallowing. - Management:

Lifestyle changes, such as weight loss, dietary adjustments, and avoiding trigger foods, combined with medications like antacids, H2 blockers, and PPIs, are central to managing GERD.

Stomach Cancer

Stomach cancer, or gastric cancer, can develop in any region of the stomach and may spread to other organs.

- Risk Factors:

Chronic H. pylori infection, smoking, a diet high in smoked and salted foods, and a family history of gastric cancer increase risk. - Symptoms:

Early stages may be asymptomatic; however, advanced cancer may cause weight loss, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal bleeding. - Treatment:

Treatment depends on the stage and may include surgery (partial or total gastrectomy), chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and targeted biological therapies.

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is characterized by delayed gastric emptying due to impaired stomach motility.

- Associated Conditions:

It is often associated with diabetes, certain medications, or idiopathic causes. - Symptoms:

Patients may experience nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and abdominal pain. - Treatment:

Management includes dietary modifications (small, frequent meals), prokinetic medications to enhance motility, and in severe cases, surgical or endoscopic interventions.

Hiatal Hernia

A hiatal hernia occurs when part of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

- Impact:

This displacement can affect the function of the LES, leading to symptoms similar to GERD. - Symptoms:

Typical complaints include heartburn, chest pain, regurgitation, and difficulty swallowing. - Management:

Mild cases may be managed with lifestyle and dietary changes, while severe cases might require surgical repair.

Functional Dyspepsia

Functional dyspepsia, commonly referred to as indigestion, is characterized by chronic upper abdominal discomfort without an identifiable cause.

- Symptoms:

These include bloating, nausea, early satiety, and epigastric pain. - Treatment:

Treatment often involves dietary adjustments, stress management, and medications like PPIs, H2 blockers, and prokinetics to alleviate symptoms.

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare condition caused by gastrin-secreting tumors (gastrinomas) that lead to excessive gastric acid production and recurrent peptic ulcers.

- Symptoms:

Patients typically experience severe abdominal pain, diarrhea, and ulcers that are resistant to standard treatments. - Management:

Treatment includes high-dose acid-suppressing medications and, when feasible, surgical removal of the gastrinomas.

Diagnostic Methods for Stomach Conditions

A precise diagnosis of stomach disorders is essential for effective treatment. Various diagnostic tools and procedures are used to assess stomach structure, function, and pathology.

Medical History and Physical Examination

- Comprehensive Medical History:

Gathering details about symptoms, dietary habits, medication use, and family history is crucial in forming a diagnosis. - Physical Examination:

Doctors assess abdominal tenderness, organ enlargement, and bowel sounds by palpating the abdomen and auscultating with a stethoscope.

Laboratory Tests

- Blood Tests:

A complete blood count (CBC), liver function tests, and markers for H. pylori infection help identify inflammation, anemia, and potential infections. - Stool Tests:

Tests like the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT) detect gastrointestinal bleeding and other abnormalities.

Endoscopy

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD):

A flexible endoscope is inserted through the mouth to directly visualize the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. This procedure is vital for diagnosing gastritis, ulcers, hiatal hernias, and stomach cancer, and allows for biopsies. - Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS):

Combines endoscopy with ultrasound imaging to obtain detailed views of the stomach wall and surrounding tissues, particularly useful in staging tumors and evaluating submucosal lesions.

Imaging Studies

- X-rays with Barium Swallow:

After ingesting a barium solution, X-rays reveal the outline of the stomach and can detect ulcers, tumors, and structural abnormalities. - Computed Tomography (CT) Scan:

Provides detailed cross-sectional images to evaluate the stomach and adjacent organs, detect masses, and assess complications. - Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

Offers high-contrast images of soft tissues, aiding in the evaluation of tumors, inflammation, and other subtle abnormalities. - Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scan:

Often combined with CT, PET scans identify areas of increased metabolic activity suggestive of malignancy.

Functional Tests

- Gastric Emptying Study:

Assesses the rate at which the stomach empties its contents into the small intestine, helping diagnose gastroparesis. - 24-hour pH Monitoring:

Measures the acidity in the esophagus over a full day to evaluate GERD severity and treatment efficacy. - Esophageal Manometry:

Assesses the pressure and coordination of esophageal muscles, providing insight into motility disorders.

Biopsy and Histopathological Analysis

- Biopsy:

Tissue samples obtained during endoscopy allow for microscopic evaluation of the stomach lining to detect inflammation, infection, dysplasia, or cancer. - Histopathology:

Detailed examination of biopsy specimens confirms diagnoses and guides treatment decisions.

Treatment Options for Stomach Disorders

Managing stomach conditions requires a multi-pronged approach, ranging from conservative therapies to surgical interventions. Treatment is tailored to the specific diagnosis, symptom severity, and overall patient health.

Medications

- Antacids:

Over-the-counter remedies that neutralize stomach acid and provide quick relief from heartburn and indigestion. - Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs):

Medications like omeprazole and esomeprazole reduce acid production, effectively treating GERD, peptic ulcers, and gastritis. - H2 Receptor Blockers:

Drugs such as famotidine and ranitidine decrease acid secretion, serving as an alternative to PPIs. - Antibiotics:

Used to eradicate H. pylori infection in cases of gastritis and peptic ulcers, typically in combination with acid-suppressing medications. - Prokinetics:

Agents like metoclopramide improve gastric motility and are especially beneficial for gastroparesis. - Antiemetics:

Medications such as ondansetron alleviate nausea and vomiting associated with various stomach disorders. - Cytoprotective Agents:

Sucralfate and misoprostol protect the stomach lining, promoting healing in ulcerative conditions.

Lifestyle and Dietary Modifications

- Dietary Adjustments:

Avoid foods and beverages that irritate the stomach, such as spicy, acidic, or fatty foods, caffeine, and alcohol. Eating smaller, more frequent meals can prevent overloading the stomach. - Hydration:

Adequate water intake supports digestion and helps prevent constipation. - Weight Management:

Maintaining a healthy weight reduces pressure on the stomach and decreases the risk of GERD. - Stress Management:

Techniques like mindfulness, meditation, and deep breathing help reduce stress, which can exacerbate stomach issues. - Avoid Smoking:

Smoking weakens the lower esophageal sphincter and impairs the protective lining of the stomach, increasing the risk of ulcers and GERD.

Surgical Interventions

- Fundoplication:

A surgical procedure to treat GERD by wrapping the upper part of the stomach around the lower esophagus to strengthen the LES. - Gastrectomy:

Partial or total removal of the stomach, performed for stomach cancer or refractory ulcers. - Pyloroplasty:

Surgical enlargement of the pyloric channel to improve gastric emptying in gastroparesis. - Gastric Bypass:

A bariatric procedure that alters the stomach and small intestine to promote weight loss, which can indirectly improve stomach function.

Endoscopic Procedures

- Endoscopic Mucosal Resection (EMR) & Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD):

Minimally invasive techniques used to remove precancerous or early cancerous lesions from the stomach lining. - Stent Placement:

For cases of gastric outlet obstruction, endoscopic stenting can help maintain an open passage between the stomach and small intestine.

Innovative and Emerging Therapies

- Stem Cell Therapy:

Research is ongoing into the use of stem cells to regenerate damaged stomach tissue, offering potential new treatments for chronic ulcers and other conditions. - Biologic Agents:

Targeted therapies using biologics are being developed to treat inflammatory conditions affecting the stomach, such as Crohn’s disease. - Gene Therapy:

Although still experimental, gene therapy may one day offer solutions for congenital stomach disorders by correcting genetic abnormalities.

Supplements for Stomach Health

Certain supplements can support stomach health by promoting a balanced gut environment, protecting the mucosal lining, and aiding digestion. Here are some supplements with proven benefits:

Vitamins and Minerals

- Vitamin C:

An antioxidant that supports immune function and helps protect the stomach lining. - Vitamin B12:

Essential for red blood cell production and neurological health, particularly important for individuals with impaired absorption. - Iron:

Supports hemoglobin production and helps prevent anemia, which can be exacerbated by chronic stomach conditions. - Vitamin D:

Modulates immune responses and aids in the absorption of calcium, supporting overall gastrointestinal health.

Herbal Supplements

- Ginger:

Known for its anti-nausea and anti-inflammatory properties, ginger can relieve indigestion and stomach discomfort. - Turmeric:

Contains curcumin, which has potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, protecting the stomach lining. - Licorice Root (DGL):

Deglycyrrhizinated licorice helps soothe and protect the stomach lining, reducing symptoms of gastritis and ulcers.

Digestive Enzymes

- Enzyme Blends:

Supplements containing amylase, protease, and lipase can aid digestion by helping break down carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, respectively, ensuring better nutrient absorption.

Antioxidants

- Quercetin:

A natural flavonoid with anti-inflammatory properties that helps protect the stomach lining. - Resveratrol:

An antioxidant found in grapes and berries that reduces oxidative stress and may lower the risk of gastritis.

Probiotics

- Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium:

These strains help maintain a healthy balance of gut bacteria, improving digestion and reducing inflammation in the stomach.

Additional Support

- Fiber Supplements:

Soluble fiber supports digestive health by regulating bowel movements and feeding beneficial gut bacteria. - Omega-3 Fatty Acids:

These essential fats reduce inflammation and support overall gastrointestinal health.

Lifestyle and Dietary Guidelines for Stomach Health

Maintaining a healthy stomach involves adopting lifestyle habits and dietary practices that support digestive function and overall wellness. Here are some practical recommendations:

- Balanced Diet:

Focus on consuming a variety of nutrient-rich foods, including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats to nourish the stomach and support digestion. - Hydration:

Aim to drink at least eight cups of water daily to assist in digestion and prevent constipation. - Mindful Eating:

Eat slowly, chew thoroughly, and avoid overeating to prevent digestive overload and reduce the risk of indigestion. - Avoid Irritants:

Limit consumption of alcohol, caffeine, spicy foods, and acidic beverages, which can irritate the stomach lining. - Stress Management:

Practice stress-reduction techniques such as yoga, meditation, or deep breathing exercises to support healthy digestion. - Regular Physical Activity:

Exercise regularly to improve circulation, stimulate gut motility, and help maintain a healthy weight. - Smoking Cessation:

Avoid smoking to protect the LES and reduce the risk of developing GERD and stomach ulcers. - Weight Management:

Maintain a healthy weight to reduce pressure on the stomach and minimize the risk of reflux and other digestive issues. - Routine Check-Ups:

Regular medical examinations can help detect and address stomach conditions early, ensuring timely intervention. - Adequate Sleep:

Ensure 7–9 hours of quality sleep per night to allow the body to repair and support digestive function. - Healthy Cooking Methods:

Opt for baking, steaming, or grilling rather than frying to reduce the intake of unhealthy fats and avoid stomach irritation.

Trusted Resources for Stomach Health

For those seeking further information on stomach health, numerous reputable resources offer evidence-based insights and practical guidance.

Books

- “The Complete Stomach Health Guide” by Dr. Maged A. Tanios

A comprehensive resource covering stomach anatomy, common disorders, and treatment options. - “The Sensitive Stomach” by Dr. Brian E. Lacy

Provides practical advice on managing stomach disorders and maintaining a healthy digestive system. - “Your Stomach: What Is Really Making You Miserable and What to Do About It” by Dr. Jonathan V. Wright

Offers an in-depth look at various stomach conditions and natural treatment approaches.

Academic Journals

- Gastroenterology:

The leading journal in digestive health, publishing peer-reviewed studies on the latest advancements in stomach-related research. - The American Journal of Gastroenterology:

Provides clinical studies, reviews, and guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of stomach and digestive disorders.

Mobile Applications

- MyGut:

An app that helps users track digestive health, monitor symptoms, and manage dietary habits. - Cara Care:

Offers personalized nutrition plans, symptom tracking, and support for individuals with digestive disorders. - MyFitnessPal:

Assists in tracking dietary intake and exercise, contributing to overall digestive and stomach health.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of the stomach?

The stomach is responsible for mechanically and chemically breaking down food, mixing it with gastric juices to form chyme, and regulating the passage of this partially digested food into the small intestine.

How does the stomach protect itself from its own acid?

The stomach protects itself through the secretion of mucus and bicarbonate by its mucosal lining, which forms a protective barrier against the corrosive effects of hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes.

What causes peptic ulcers?

Peptic ulcers typically result from the erosion of the stomach lining due to H. pylori infection or long-term use of NSAIDs, leading to a breakdown of the protective mucosal barrier.

How is GERD managed?

GERD is managed through lifestyle changes such as weight loss and dietary adjustments, along with medications like antacids, H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors. In severe cases, surgical intervention may be considered.

What role do probiotics play in stomach health?

Probiotics help maintain a healthy balance of gut bacteria, support digestion, reduce inflammation, and strengthen the immune system, all of which contribute to overall stomach health.

Disclaimer & Sharing

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider regarding any concerns or before starting any new treatment.

If you found this guide helpful, please share it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred social platform to help spread awareness and promote stomach health.