A coronary artery calcium (CAC) scan is a five-minute, noninvasive CT that quantifies calcified plaque in your coronary arteries. For people focused on healthspan, it offers something most lab panels cannot: a direct read on atherosclerotic burden today and how that burden maps to future cardiovascular risk. Used thoughtfully, CAC can sharpen decisions about lifestyle intensity, lipid-lowering therapy, and blood pressure goals—and it can prevent both overtreatment and false reassurance. This guide explains what CAC measures, who benefits, how to interpret scores and percentiles, when to repeat (and when not to), how radiation and cost fit in, and how CAC integrates with other risk markers such as ApoB, blood pressure, and glucose control. For a wider view of objective tracking in healthy aging, see our overview of longevity biomarkers and tools.

Table of Contents

- What CAC Measures and Why It Predicts Events

- Who Should Consider Testing and When

- Understanding Scores: 0, 1–99, 100–399, 400+ (and Percentiles)

- Radiation, Cost, and Access: Practical Considerations

- When to Repeat CAC and When Not To

- How CAC Fits with Other Risk Markers (ApoB, BP, Diabetes)

- Questions to Take to Your Clinician

What CAC Measures and Why It Predicts Events

CAC quantifies calcified atherosclerotic plaque using the Agatston method, which multiplies plaque area by a density factor based on Hounsfield units. The reading is not a cholesterol test or a stress test. It is a structural scan that tells you whether calcified plaque exists and—crucially—how much. Because calcification generally occurs as plaques mature and heal, CAC correlates with lifetime exposure to atherogenic particles and cumulative vascular injury. While a CAC score does not measure soft (non-calcified) plaque directly, higher CAC scores track tightly with total plaque burden and risk of future events.

Why does CAC predict cardiovascular events so well? Three reasons stand out. First, CAC integrates long-term biology. A single LDL-C or ApoB value is a snapshot; CAC reflects decades of exposure. Second, CAC is objective and reproducible when performed on the same scanner with a standardized protocol. Third, CAC sorts people into risk strata that better match absolute risk than age and risk factors alone. Two 55-year-olds with identical lipid profiles can have very different CAC results—and very different event risks.

Understanding the limitations helps you interpret results wisely. CAC can be zero in the presence of non-calcified plaque, especially in younger adults, smokers, or those with diabetes. It cannot localize a future heart attack. It cannot replace clinical judgment or eliminate the value of lifestyle modification. It also does not measure stenosis. A very high CAC may coexist with nonobstructive disease, and a low CAC does not rule out spasm, microvascular disease, or acute plaque rupture unrelated to calcification.

What about vascular “calcification equals stability”? It is true that dense calcification can stabilize plaques. Yet the overall burden—how many plaques, how diffuse, how extensive—drives risk. In prevention, CAC is best used as a risk-refinement tool to tailor treatment intensity: who needs statins (and how strong), who might benefit from ezetimibe or a PCSK9 inhibitor, who warrants tighter blood pressure targets, and who can reasonably defer pharmacotherapy while doubling down on lifestyle.

Finally, CAC does something psychologically powerful: it converts abstract risk into a tangible number. When people see a score, adherence to exercise, diet, and medications tends to improve. That behavior change—sustained over years—is where the longevity payoff lives.

Who Should Consider Testing and When

CAC is most helpful when traditional risk calculators leave you uncertain. Common scenarios include adults 40–75 years old with borderline or intermediate 10-year risk by pooled cohort equations; younger adults with a worrisome family history; and individuals with risk “mismatch” (for example, very high LDL-C but pristine lifestyle, or excellent lipids but a strong family history of premature coronary disease). In these cases, CAC can nudge the decision toward more or less intensive therapy with greater confidence.

A CAC score of zero can support deferring statins in truly low-risk individuals—especially when paired with healthy blood pressure, a favorable ApoB, and no smoking. Exceptions where a zero may not be reassuring include diabetes, persistent LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, chronic kidney disease, inflammatory conditions, and heavy tobacco exposure. In these groups, lifetime risk is high even if calcification has not yet appeared.

For people with borderline or intermediate risk (roughly 5%–20% 10-year risk), CAC can be the tie-breaker. Scores of 1–99 often support starting a moderate-intensity statin if age is ≥55, while scores ≥100 generally tip the balance toward statin therapy plus lifestyle tightening. If someone is already on therapy and wondering about intensification, CAC can help frame the discussion: higher scores argue for lower ApoB targets, more diligent blood pressure control, and tighter glucose management.

Age matters. In younger adults (<45), CAC is more likely to be zero. A nonzero score at a young age, however, is a red flag and suggests aggressive risk reduction. In older adults (>75), calcification becomes more common, and interpretation should center on absolute score, distribution, symptoms, and overall health goals rather than percentiles alone.

Equity and access also matter. CAC can be especially helpful for individuals whose traditional risk may be underestimated—women with strong risk enhancers (e.g., hypertensive disorders of pregnancy), South Asian ancestry, or a family history of early myocardial infarction. It can also prevent overtreatment in people with borderline risk but clean arteries.

If blood pressure is a driver of your risk conversation, consider how you measure it. Clinic-only readings can misclassify risk. In selected cases, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring clarifies whether hypertension is sustained or situational—and that clarity pairs well with CAC in deciding next steps.

Understanding Scores: 0, 1–99, 100–399, 400+ (and Percentiles)

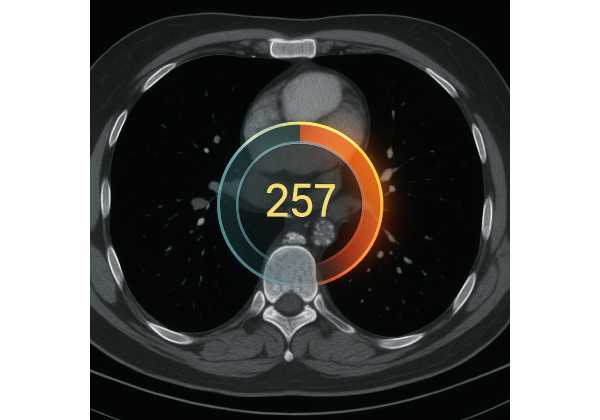

CAC is reported as an Agatston score and, ideally, as a percentile for age, sex, and ethnicity. Here is how to translate the numbers into action-oriented language:

CAC = 0 (often called “power of zero”). Event rates over the next 5–10 years tend to be very low. For many people at borderline risk, a score of zero supports deferring statin therapy while focusing on lifestyle, sleep, and blood pressure. It does not negate therapy in high-risk conditions (diabetes, LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, established ASCVD in other beds). Nor does it mean “do nothing”; it means “do the basics exceptionally well.”

CAC 1–99. Risk is elevated compared with zero. In adults over ~55, any nonzero CAC usually pushes the balance toward a statin, especially with other risk enhancers. The upper end of this range (e.g., 75–99) deserves nearly as much attention as 100–199 if you are young or your percentile is high.

CAC 100–399. This range signals definite atherosclerotic burden. Most people benefit from at least moderate- to high-intensity statins, tighter ApoB targets, and proactive lifestyle upgrades. Blood pressure goals should be deliberate, and clinicians may discuss low-dose aspirin in selected individuals with low bleeding risk.

CAC ≥400 (and especially ≥1000). High and very high plaque burden. Management resembles secondary prevention in intensity: high-intensity statins (and often add-on agents), lower ApoB goals, careful blood pressure control, and robust lifestyle work. Avoid therapeutic inertia.

Percentiles add context, particularly for younger people. A CAC of 20 in a 40-year-old man may sit at the 95th percentile and matter more than the absolute value suggests. Conversely, a CAC of 120 in a much older adult may sit near the median and call for risk reduction without alarm. Always weigh both the absolute score and the percentile alongside clinical factors.

Distribution and density provide nuance. Left main involvement, diffuse multivessel calcification, and rapidly rising scores convey higher risk than a single, dense, small lesion. If your report mentions noncalcified plaque from another scan, that finding adds weight even when CAC is low.

Metabolic health influences interpretation, too. Elevated A1c, fasting glucose, or fasting insulin implies more “drivers” for plaque growth. If your CAC result raises questions about glycemic resilience, review our primer on A1c and fasting insulin to align glucose goals with arterial health.

Radiation, Cost, and Access: Practical Considerations

Radiation. Modern calcium scoring protocols typically deliver a low effective dose—often around ~1 mSv, though actual doses vary with scanner model, protocol, and body habitus. Dose-reduction techniques (prospective ECG triggering, lower tube voltage, iterative reconstruction, and appropriate field of view) continue to push exposures down. As with any medical imaging, the principle is “as low as reasonably achievable.” For perspective, ~1 mSv is in the neighborhood of several months of background radiation. If you have had multiple CT scans or you are very young, the cumulative dose conversation deserves extra care.

Cost and insurance. CAC is frequently offered as a self-pay test, with prices ranging from promotional \$50–\$150 in some centers to a few hundred dollars elsewhere. Insurance coverage varies by region and indication. Because the scan is quick, many centers bundle scheduling and scanning in a single visit. Ask about the fee, whether interpretation is included, and whether the report provides both the Agatston score and the age/sex percentile.

Access and quality. Quality matters more than brand. A noncontrast, ECG-gated CT with a standardized protocol is the goal. If you plan to repeat CAC in the future, try to use the same facility and scanner model to minimize variability. A structured report that specifies total score, vessel-specific scores, density, and any notable distribution (e.g., left main) is helpful for longitudinal care. If incidental findings appear (lung nodules, aortic calcification), expect guidance on whether follow-up imaging is appropriate.

Preparation and experience. There is no contrast and no needles. Plan to avoid vigorous exercise right beforehand, remove chest metal, and hold still for a short breath-hold. Claustrophobia is uncommon due to the wide gantry. Most people are in and out in under 20 minutes.

Equity and ethics. CAC can be empowering, but it should not create a barrier to care. If cost or travel is limiting, talk with your clinician about whether your current risk can be managed without a scan. For those with established ASCVD, a CAC score no longer changes treatment—resources are better spent on aggressive risk-factor control.

Interpreting incidentally detected CAC. If a prior chest CT mentions coronary calcification, that is a meaningful risk signal even if no formal Agatston score was calculated. Discuss whether a dedicated CAC scan adds value or whether you can proceed directly to prevention steps based on that finding.

When to Repeat CAC and When Not To

Repeating CAC is not routine. The goal is to inform decisions, not to chase numbers. Consider these principles:

After CAC = 0. If risk is low and modifiable factors are well controlled, repeating in about 5 years is reasonable. If your risk changes—new diabetes, tobacco relapse, LDL-C rises, significant weight gain, or a new family event—an earlier recheck at ~3 years can be considered. Younger adults with strong risk enhancers may also choose a shorter interval, especially if the initial percentile was high for age despite a zero score.

After CAC 1–99. Focus first on executing a prevention plan: nutrition, activity, sleep, statin adherence if indicated, and blood pressure control. A repeat in ~3–5 years can show whether plaque burden remains stable or accelerates. Rising scores alone do not prove treatment failure; calcification can increase as plaques stabilize. What matters is the clinical trajectory: ApoB reduction, weight and fitness trends, blood pressure control, and symptom status.

After CAC 100–399 or ≥400. Management intensity is already high. Routine rescanning rarely alters care. Consider a repeat only if results might change decisions—e.g., uncertainty about therapy adherence or a major change in risk factors. If symptoms develop, functional testing or coronary CT angiography may be more informative than repeating CAC.

Situations to avoid frequent repeat scanning. Annual CAC adds radiation and rarely changes management. If you already qualify for intensive therapy based on score and clinical profile, keep the focus on executing that plan. Similarly, people with known coronary disease do not benefit from CAC monitoring; care should target symptom control and secondary prevention metrics.

Using progression wisely. When CAC is repeated, look beyond the raw delta. Compare percentiles, distribution, and density. A modest absolute increase at a very low baseline may carry little clinical meaning, while a sharp rise from 150 to 350 in a short span might prompt a deeper look at adherence, ApoB levels, lipoprotein(a), secondary causes (hypothyroidism, nephrotic range proteinuria), and lifestyle gaps.

If family risk is striking or you carry a high genetic burden, checking your lipoprotein(a) status can clarify why calcification appeared earlier or progressed faster than expected, and it can guide how aggressively you and your clinician aim with LDL-C/ApoB lowering.

How CAC Fits with Other Risk Markers (ApoB, BP, Diabetes)

Think of CAC as a stage-setter. It tells you whether enough plaque has accumulated to materially change your risk over the next decade. Other markers tell you how to act on that information.

ApoB and LDL-C. ApoB counts atherogenic particles directly. Elevated ApoB (or non-HDL-C) is the principal driver of plaque accrual. If CAC is nonzero, lowering ApoB becomes a priority. Practical checkpoints: confirm adherence to statins, consider ezetimibe if ApoB remains above target, and escalate to PCSK9 inhibitors in very high-risk cases. The exact ApoB target is individualized; a lower target is reasonable with higher CAC, left main involvement, diabetes, or family history of premature events. For deeper context on lipid prioritization, see ApoB as a primary marker.

Blood pressure. Hypertension accelerates plaque growth and destabilizes plaques. When CAC is elevated, the case for tighter home blood pressure targets strengthens. Confirm accurate measurement at home, address sodium and alcohol intake, and personalize medication combinations that favor vascular protection (ACEi/ARB, thiazide-like diuretics, long-acting calcium channel blockers).

Glucose control. Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance promote endothelial dysfunction and plaque formation. If CAC is positive, aim for sustained glucose stability: consistent fiber-rich meals, resistance training, and sleep regularity. In diabetes or prediabetes, medications with cardiovascular benefit (SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists) warrant discussion, independent of their weight effects.

Inflammation and lifestyle. hs-CRP is a non-specific inflammation marker; when elevated alongside positive CAC, it argues for weight management, sleep optimization, periodontal care, and aerobic plus resistance training rather than anti-inflammatory supplements. Sleep disorders (especially sleep apnea) can worsen blood pressure and metabolic health and should be treated aggressively.

Age and percentiles. Younger individuals with high-percentile CAC may adopt secondary-prevention–like targets earlier. Older adults with modest CAC and excellent fitness may focus on maintaining function, strength, and balance while keeping ApoB and blood pressure in reasonable ranges.

Atypical findings. Very high CAC (≥1000) suggests diffuse disease and justifies comprehensive risk-factor control. Left main calcification and rapid score growth over a short interval carry extra weight. In these scenarios, more intensive lipid lowering, stricter blood pressure control, and careful glucose management are appropriate.

Putting it together. CAC points to “how hard” to push prevention; ApoB, blood pressure, and glucose metrics show “how well” you are executing. Pair the two and you have a durable framework for longevity-focused cardiovascular care.

Questions to Take to Your Clinician

- Does my CAC score change my 10-year and lifetime risk enough to alter therapy? Ask for numbers: estimated absolute risk before and after CAC, and what risk threshold your clinician uses for statins, add-on agents, and blood pressure targets.

- What ApoB or non-HDL-C goal aligns with my CAC result and overall profile? Clarify whether your target is “good enough” or whether a lower number is advisable given your score, family history, or diabetes.

- How do my home blood pressure readings fit into this plan? Bring a two-week log and your device. Decide on home or ambulatory confirmation if readings are variable.

- Do I need aspirin? Discuss benefits and bleeding risk in light of your CAC score, age, and comorbidities. Many people do not need aspirin; some with higher CAC and low bleeding risk might.

- Should I repeat CAC—and when? Agree on a specific interval (or a plan not to repeat) and what result would actually change management.

- Do I need additional imaging? If symptoms, very high CAC (especially with left main involvement), or uncertainty exists, ask whether coronary CT angiography or functional testing is appropriate.

- What is the plan for lifestyle execution? Specify nutrition steps (e.g., fiber and protein targets), resistance and cardio benchmarks, alcohol and sodium limits, and sleep goals. Ask how you will measure success over the next 3–6 months.

- Which medications best fit my profile? If intensifying lipids, discuss ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors. If blood pressure is elevated, review combinations that support kidney and vascular health.

- How will we track progress? Decide on an interval for ApoB, home blood pressure summaries, weight/waist updates, and symptom check-ins. Define what would trigger a treatment adjustment.

Bring your actual report (with vessel-specific scores and percentile), a home blood pressure log, recent labs, family history notes, and a one-page summary of your lifestyle pattern. A focused discussion with clear metrics prevents drift and keeps prevention on course.

References

- 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines 2019 (Guideline)

- Coronary Artery Calcium Staging to Guide Preventive Interventions: A Proposal and Call to Action 2024

- Radiation Doses in Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 2023

- Ten-year association of coronary artery calcium with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) 2018

- Coronary artery calcium scoring in primary care 2025

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes and does not replace personalized medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Decisions about CAC testing, lipid-lowering therapy, blood pressure targets, aspirin, or follow-up imaging should be made with a qualified clinician who knows your history, medications, and risk profile. If you have chest pain, shortness of breath, or other concerning symptoms, seek urgent care.

If you found this guide useful, please consider sharing it on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), or your preferred platform, and follow us for future updates. Your support helps us continue creating evidence-based health content.